theartsdesk in Tbilisi: The Dilemma over Georgian Architecture | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Tbilisi: The Dilemma over Georgian Architecture

theartsdesk in Tbilisi: The Dilemma over Georgian Architecture

Row splits artists and residents as picturesque old houses are bulldozed

In Tbilisi, Georgia, artists and art historians are calling for the Government to stop destroying their classic Old Town with its winding streets and wooden balconies. New organisations have been formed, exhibitions held to publicise this creeping eradication of history. Now another grand, once-protected building, the former Institute of Marxism and Leninism, has appeared in the cross-hairs.

When Europe’s Futurist movement briefly made Tbilisi its spiritual refuge in the early 1920s, the Georgian avant-garde rightly felt themselves riding the crest of a new social aesthetic. This balmy Silk Road city, built around hot springs underneath the craggy Greater Caucasus, had always inspired artists and intellectuals, Pushkin, Lermontov and Tolstoy among them. So no surprise that when the time came to put the artistic ideas into political action Georgia found itself choosing the more tolerant, Menshevik ("minority") school of communism, rather than Bolshevism.

As the world’s first and only Menshevik nation, in 1919 Georgia received many admiring visitors including Ramsay MacDonald (later Britain’s first socialist prime minister). But inevitably it found itself at the wrong end of Revolution. In 1921 the government was brutally swept aside by the invading Red Army, then re-defined in terms of the glorious "dictatorship of the proletariat".

Today the fully liberated, free-market city is finding itself facing a new kind of state repossession of aesthetics. A number of artists, architects and academics are wondering how to stop their own Government from wiping the history out of the older parts of their city. The last 18 months have seen a furious process of renovation ripping through the chaotic streets of the Old Town - to their great dismay and that of most of the tourists visiting this delightful capital of bending filigree balconies and hospitable owners.

Under the title "New Life for Old Tbilisi" squads of mini-bulldozers and millions of dollars and euros (mostly Western-sourced or donated) have been let loose on several key areas of old Tbilisi. Several miles of 17th, 18th and 19th-century walls have been removed to be replaced by reinforced concrete, or breeze-block, the houses redesigned as pastiches of themselves, usually with one or two extra floors, occasionally to be re-fronted with the same bricks, sliced down the middle.

[bg|/Architecture/Tbilisi_letter]

- Photographs courtesy the campaign page 'Old Tbilisi Identity and Spirit' on Facebook, credits Maya Tavartkiladze-Razmadze, Rati Kartvelishvili, Marita Merkviladze, Molly Topuridze, Angelique Jo, Nestan Tatarashvili, Molly Topuridze, Marita Merkviladze, Gela Chachua, Katerina Sharapka, Levan Dolidze, Salome Gugushauri, Gela Chachua, Maya Tavartkiladze-Razmadze, Giorgi Pruidze, Levan Kintsurashvili, Ann Beridze & Marita Merkviladze

The dilemma facing those Georgians who honour their own history is that the majority of the Old Town inhabitants, along with the Georgian President, Misha Saakashvili, approve of the changes. Those holding the country’s purse strings strongly believe that knocking down the old and replacing it with reinforced concrete, glass and steel (instead of slower, more culturally sensitive renovation, as found in other Eastern European capitals) is a sign of progress and companionship with the international community.

But most of the artists, who live closer to the cutting edge in the same community, feel differently. An initial series of protests and placard-waving events achieved nothing more than a letting-off of steam. The authorities continued blithely knocking down protected buildings and touting Tbilisi as a super-free investment zone – in which, although the money is much needed for the many dilapidated buildings, the inconsistency of the zeal frightens as much as it encourages investors.

Because renovation in Tbilisi is increasingly a non-consultative process, imposed from above, some artists are starting to use innovative techniques in trying to bring local involvement back into the planning process. Recently they’ve started experimenting with the exhibition form itself. The idea is that public display need no longer be something fixed or dependent on a containing space; that the context of the show can be as important as the content.

Back in June a photographic exhibition suddenly appeared on easels set down in the centre of an architecturally sensitive area of the Old Town – Gudiashvili Square. The picturesque 19th-century square contains a couple of the finest balconied town houses in Tbilisi – one known as the Lermontov house (see main picture), because the Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov stayed there. The area is also now gravely threatened by developers.

The show, entitled The Iron Flowers of Tbilisi, presented a wide range of the beautiful wrought-iron flowers found on balconies and railings across the city, many now in need of restoration. The exhibition was deliberately held out of doors and lasted for four hours only (after dodging a couple of rain showers). However it also included musicians, food and a competition ("guess the location of the balconies…") with the prizes as the photographs themselves. With help of a Facebook page ("Tiflis Hamqari") the party atmosphere drew many people (including briefly, the Mayor) – and significantly, far more than a previous demonstration in the same spot.

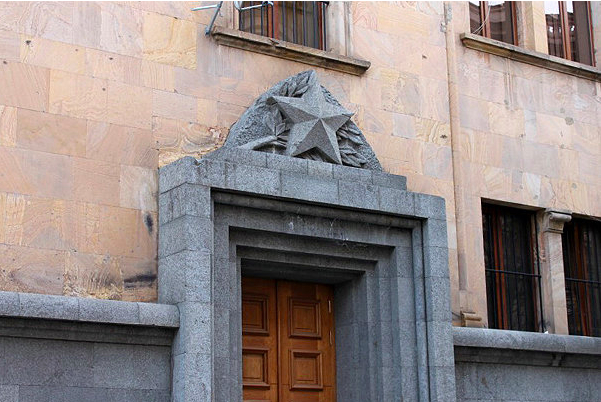

The exhibition’s principal photographer was Tsira Elisashvili, also an art historian and lecturer at the university. "Our aim is to provoke local awareness about the beauty of what people already have but don’t know they have," she says. "This is a big problem in Tbilisi. I like to take my students from university out into the streets and just point things out, sometimes even their own balconies. This helps them understand their history, often for the first time." That history, of course, also includes the Soviet buildings, such as the Parliament (pictured left), whose communist symbols are now the subject of passionate campaigns to strip them out, even when intrinsic to the building.

The exhibition’s principal photographer was Tsira Elisashvili, also an art historian and lecturer at the university. "Our aim is to provoke local awareness about the beauty of what people already have but don’t know they have," she says. "This is a big problem in Tbilisi. I like to take my students from university out into the streets and just point things out, sometimes even their own balconies. This helps them understand their history, often for the first time." That history, of course, also includes the Soviet buildings, such as the Parliament (pictured left), whose communist symbols are now the subject of passionate campaigns to strip them out, even when intrinsic to the building.

Tsira is a member of "Hamqari", the group of artists, journalists, architects who are responsible for the easel technique which allows exhibitions to be dropped into any prominent place in the city at short notice. The new idea is to hold "consciousness-raising" events in historically sensitive positions across the city – in advance of the bulldozers.

The group’s front man is Alex Elisashvili (no relation to Tsira). As a journalist in the local Kavkasia TV station he is relatively well known and a passionate believer in his country’s history.

"Georgian people know that they love Tbilisi, but they don’t quite know what it is that they love. We want to try and help. Also we seek to make the urban planning process more open, because at the moment the rules are changed so quickly, nobody knows what kind of building is going to appear or disappear until it’s too late."

Two years ago the former Institute of Marxism and Leninism (pictured right), a grand, protected building on the city’s main Rustaveli Avenue designed by Aleksey Shchusev in the 1930s, started to be demolished behind a banner of its supposed replacement, a futuristic-looking Kempinski Hotel. Then the Kempinski group pulled out, and the building was left to collapse on its own. However, made to high Stalinist standards, it refused to budge.

Two years ago the former Institute of Marxism and Leninism (pictured right), a grand, protected building on the city’s main Rustaveli Avenue designed by Aleksey Shchusev in the 1930s, started to be demolished behind a banner of its supposed replacement, a futuristic-looking Kempinski Hotel. Then the Kempinski group pulled out, and the building was left to collapse on its own. However, made to high Stalinist standards, it refused to budge.

Last Tuesday a request was issued for tenders for its demolition, save for the façade (with a submission deadline of tomorrow week, 29 August!). Artists and historians were already out on Rustaveli Avenue by Thursday protesting this latest assault on Georgia’s national heritage and resurrecting the petition from last year.

But with so much of the rebuilding money coming from outside the country, did Alex feel that we foreigners hold any responsibility for what is happening to Tbilisi? "Yes, you do," he said simply, and gave a warm smile as if to say that this is in no way personal.

Instantly one felt the dilemma faced by all Georgians, their Government in particular. How to encourage the much-needed investment from abroad, but the right kind of investment?

Restoration is urgently required in the majority of Old Town homes, which is why many locals support their destruction and rebuilding. For Hamqari the tragedy lies in the fact that many inhabitants simply don’t know that sensitive restoration (like moving their toilets and bathrooms to inside the house; slower, more accurate reconstruction of walls; replacing the damaged sections of balconies rather than whole balconies), is actually better than a whole new, taller building in this earthquake zone (a few Old Town buildings, particularly in the Sololaki district, have received six or even seven extra floors).

Hamqari now want to hold an exhibition called Before and After, to alert local Georgian citizens to the rapid disappearance of Georgia’s sense of history over the last two decades. The aim is to time it with an international conference, Community and the Historic Environment (20-22 September), called by the Georgian organisation probably most concerned about the local style of restoration, ICOMOS, Georgia, to be held at the splendid National Library.

In other parts of the city, impromptu exhibitions have also been held by artists, like the sculpture exhibition by Irine Gachileladze, this time in a building that has been tastefully restored - the defunct cable-car base station at the top of Rustaveli Avenue. Her intriguing arrangement of large plaster legs draped over the spiral walkway (pictured left with Irine Gachileladze) had the effect this time of celebrating a positive act of renovation in the city (there is some of this too).

In other parts of the city, impromptu exhibitions have also been held by artists, like the sculpture exhibition by Irine Gachileladze, this time in a building that has been tastefully restored - the defunct cable-car base station at the top of Rustaveli Avenue. Her intriguing arrangement of large plaster legs draped over the spiral walkway (pictured left with Irine Gachileladze) had the effect this time of celebrating a positive act of renovation in the city (there is some of this too).

In the meantime Tbilisi, with the nation of Georgia in tandem, continues to launch itself purposefully into the future, with new restaurants, shops, film and theatre productions, a major renovation of the Opera building, and the always innovative visual arts festival Artisterium readying itself for its fourth incarnation in early November. It is just hoped that, unlike with their Menshevik predecessors, the new phase of modernisation will allow the nation’s extraordinarily rich past to play a living role in the design of its future.

- Peter Nasmyth is author of Georgia, in the Mountains of Poetry (Routledge) and Walking in the Caucasus, Georgia (Mta Publications)

- See theartsdesk gallery of traditional Russian wooden dacha building

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Comments

...

...