I’ve just spent four hours in the Turner Prize exhibition at Tate Britain. The shortlisted artists all show films or videos, which means that you either stay for the duration or make the decision to walk away, which feels disrespectful. For unlike paintings, drawings or photographs, which allow you to decide how long to spend in their company, the moving image tends to deprive you of agency and hold you captive.

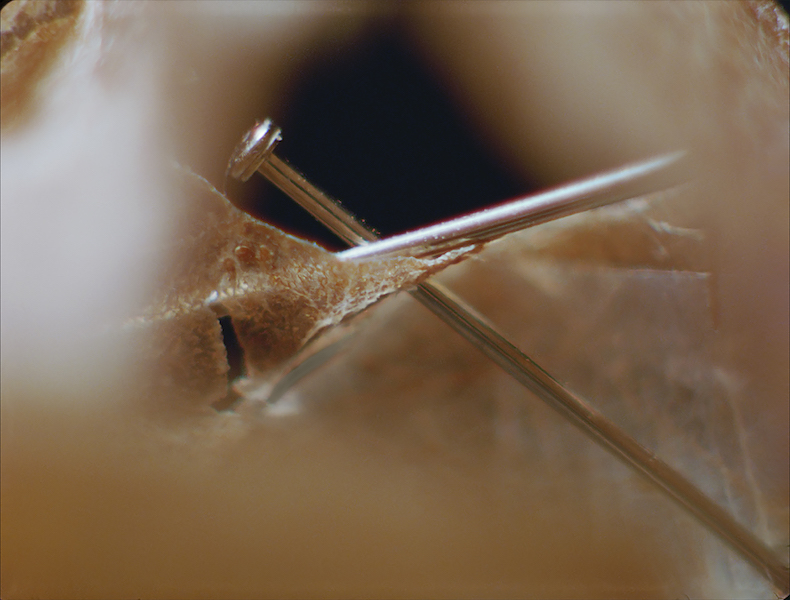

Luke Willis Thompson chose specialist macro lenses to film a sculpture by Donald Rodney who died in 1998 from sickle cell anaemia, an inherited disorder particularly affecting Africans living in the diaspora. Rodney fashioned a tiny house from his own skin; held together with pins, the sculpture (pictured below right) serves both as an ironic testament to his genetic inheritance and a fragile memorial to his waning health.

Thompson produces a fitting eulogy to this life cut short from within, as it were, by filming the little house from underneath so that one appears to be inside it, or so close that the cellular structure of Rodney’s skin fills the screen with its delicate tracery. While Human is self-evidently a film, the other parts of the trilogy could almost be mistaken for photographs and would, I think, be less problematic and more powerful as stills.

Thompson produces a fitting eulogy to this life cut short from within, as it were, by filming the little house from underneath so that one appears to be inside it, or so close that the cellular structure of Rodney’s skin fills the screen with its delicate tracery. While Human is self-evidently a film, the other parts of the trilogy could almost be mistaken for photographs and would, I think, be less problematic and more powerful as stills.

His subjects are Diamond Reynolds (pictured below left), whose partner Philando Castile was shot by police after stopping his car in St Paul’s Minnesota in 2016; Brandon, grandson of Dorothy Groce who was shot by police at her home in Brixton in September 1985; and Graeme, son of Joy Gardner who was killed by police in her home in Crouch End in July 1993. Filmed in black and white, the sitters remain more or less motionless under the scrutiny of the lens.

Thompson’s intention was, doubtless, to honour these people whose lives have been shattered by police violence, yet making them endure the camera’s unwavering gaze for what feels like an eternity seems uncomfortably like a second violation. Reference to Andy Warhol’s Screen Shots does nothing to alleviate the intrusiveness. Had the artist opted for still portraits, on the other hand, he could have conferred respect on his subjects without objectifying them. At one point Reynolds appears to be muttering silently; I couldn’t help imagining she was praying for the interminable session to end.

Naeem Mohaiemen was born in London, grew up in Bangladesh, and now lives in New York. Does this make him eligible for the Prize ? In this world of complex and shifting identities, who knows where anyone belongs socially or culturally? As it happens this, indirectly, is the subject of Tripoli Cancelled, a film inspired by a family incident. The artist’s father was stranded in Athens’ airport for nine days, in 1977, after losing his passport while changing money. That airport was closed in 2001 and now stands creepily empty, which makes it the perfect setting for a film about a man living in an abandoned airport.

Naeem Mohaiemen was born in London, grew up in Bangladesh, and now lives in New York. Does this make him eligible for the Prize ? In this world of complex and shifting identities, who knows where anyone belongs socially or culturally? As it happens this, indirectly, is the subject of Tripoli Cancelled, a film inspired by a family incident. The artist’s father was stranded in Athens’ airport for nine days, in 1977, after losing his passport while changing money. That airport was closed in 2001 and now stands creepily empty, which makes it the perfect setting for a film about a man living in an abandoned airport.

Mohaiemen’s protagonist passes the time wandering though derelict departure lounges and arrival halls, pretending to fly a defunct helicopter, speaking to imaginary pilots from the control tower, walking the wing of a grounded jumbo jet (main picture), writing letters to his wife, reading extracts from Richard Adams’ Watership Down, and trying to call his wife on a disconnected telephone. Finally he dissolves into tears while sitting on a static escalator singing Nana Mousckouri’s song Never on a Sunday.

A meditation on identity, loneliness and belonging, the film is very beguiling; but that is also its failing. Since the protagonist remains well groomed and his suit and white shirt are immaculate throughout, the physical nightmare of displacement is never alluded to; nor does one even sniff the horror of what it must be like to be stateless.

Two Meetings and a Funeral is a three-screen documentary that looks back to meetings of the Non-Aligned Movement and The Organisation of Islamic Co-operation in 1973 and ’74 when efforts were made by Third World countries to break free from US and Soviet influence and unite around socialism. Unless the subject is close to your heart, the film is unlikely to hold your attention. We are told that the younger generation of the respective countries have little interest in this historical moment, which begs the question: why, then, should we? Mohaiemen is currently completing a PhD in anthropology and this film feels rather like a research project. Charlotte Prodger’s BRIDGIT is like a stream-of-consciousness meditation on identity, gender politics and naming; except that every aspect of this immaculate video is crafted to perfection. If the juxtaposition of one beautiful image with the next appears random, the soundtrack often lingers on to establish a connection and imply continuity of thought, feeling or idea. A red lorry is seen from a train speeding along a motorway in the highlands of Scotland; a red cargo ship glides over choppy seas; a fur-lined hood is silhouetted against branches laden with cherry blossom; the empty deck of a ferry (pictured above) rises and falls against the horizon under a stormy sky. It's hard to believe that such exquisite images were shot on a mobile phone, except that the camera follows the gentle movement of the artist’s ribcage as she breathes, which gives the footage a soothing, repetitive pulse.

Charlotte Prodger’s BRIDGIT is like a stream-of-consciousness meditation on identity, gender politics and naming; except that every aspect of this immaculate video is crafted to perfection. If the juxtaposition of one beautiful image with the next appears random, the soundtrack often lingers on to establish a connection and imply continuity of thought, feeling or idea. A red lorry is seen from a train speeding along a motorway in the highlands of Scotland; a red cargo ship glides over choppy seas; a fur-lined hood is silhouetted against branches laden with cherry blossom; the empty deck of a ferry (pictured above) rises and falls against the horizon under a stormy sky. It's hard to believe that such exquisite images were shot on a mobile phone, except that the camera follows the gentle movement of the artist’s ribcage as she breathes, which gives the footage a soothing, repetitive pulse.

Meanwhile, on the soundtrack Prodger recalls growing up in Aberdeenshire where Julian Cope was researching the cult of the neolithic mother goddess known variously as Bridgit, Bride, Brid, Brig, Brizo, Breeshey, Britomartis and Bree. She quotes Sandy Stone, the virtual systems theorist who also goes by multiple names and observes that, prior to the Domesday Book, people’s names would change in accordance with their age, experience and status. Identity was perceived as fluid and shifting; this prompts her to remember the many times she has been mistaken for a boy – wrongly labelled as it were. When being given a general anaesthetic, Prodger was advised to think of something pleasing; her response was plural rather than singular – a mental slide show of different fields. BRIDGIT functions in a similar way; it explores the plurality of being through images that invite you to enter an interior space where ideas are transmitted by association as much as by logic. Forensic Architecture is a collective of architects, film makers, lawyers, journalists and other specialists who use their expertise to investigate allegations of state and corporate violence. Evidence gathered by people on the spot is analysed and, in conjunction with organisations such as the United Nations and Amnesty International, is then presented as evidence. On display is some footage shot during a raid by Israeli police on a Bedouin village in the Negev, in January 2017. Israel is intent on clearing the area of what they identify as illegal encampments to make way for Jewish settlements.

Forensic Architecture is a collective of architects, film makers, lawyers, journalists and other specialists who use their expertise to investigate allegations of state and corporate violence. Evidence gathered by people on the spot is analysed and, in conjunction with organisations such as the United Nations and Amnesty International, is then presented as evidence. On display is some footage shot during a raid by Israeli police on a Bedouin village in the Negev, in January 2017. Israel is intent on clearing the area of what they identify as illegal encampments to make way for Jewish settlements.

Two people were killed in the raid, a policeman and a villager whom the Israeli authorities claim was a terrorist who attacked the police. Taken in the dark by a member of the local group ActiveStills, the snippets of film reveal nothing to the untutored eye but noise and chaos. The film is projected onto a model (pictured below) constructed by Forensic Architecture to clarify the positions of all the protagonists and their vehicles. And in the next room, they explain the process through which additional information gleaned from sources such as aerial shots and bodycams was analysed and collated with the gunshots recorded on film (pictured above). By establishing the sequence of events, second by second, they were able to reveal that the Israeli version of events was false. Alongside this fascinating display is an ongoing project in which aerial photographs are used to show that the Bedouin settlements were there long before the State of Israel was established and are therefore legal.  But is this art ? The answer must surely be “no”, it is far more important than that. This is the kind of education we all need, especially in the current, looking-glass world where truth has been relegated to history and unscrupulous governments behave as if repeating a fiction often enough makes it true or, at least, gives it precedence over fact. Thank God someone has the technology, the expertise and the will to refute the lies. All power to their collective elbow. Give them the Prize!

But is this art ? The answer must surely be “no”, it is far more important than that. This is the kind of education we all need, especially in the current, looking-glass world where truth has been relegated to history and unscrupulous governments behave as if repeating a fiction often enough makes it true or, at least, gives it precedence over fact. Thank God someone has the technology, the expertise and the will to refute the lies. All power to their collective elbow. Give them the Prize!

- The Turner Prize at Tate Britain until 6 January, The winner to be announced on 4 December

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)