In 1920, Man Ray, now better known for his solarized photographs, produced a sculpture made from found objects. L'Enigme d'Isidore Ducasse, named after the 19th-century French poet who used the pseudonym Comte de Lautréamont, is a sewing machine wrapped in a wool blanket and tied with string. The title refers to the poet’s evocation of the strange, even threatening beauty of familiar objects in startling juxtaposition, and is a line later adopted by André Breton to suggest Surrealist dislocation. With regard to Man Ray’s sculpture, we have to take it on trust that it’s a sewing machine under that blanket.

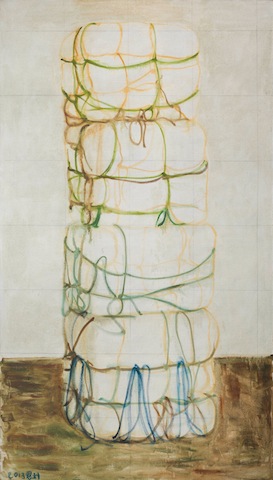

I think of May Ray when I encounter the work of Chinese artist Zhang Enli. I think of the American Surrealist in passing when I see Zhang’s huge paintings of packages tied with string, and then later, because Zhang’s work evokes a genuinely disquieting sense of beauty and dislocation, as I sit in a prison-like box made of plywood whose interior is painted with swirling clouds of colour – muted dirty greens and blue tones. I also think of striking pairings both within Zhang’s own paintings, and as his work appears alongside the photographs of Alex Van Gelder, who takes pictures of blood and animal viscera, all carefully arranged and beautifully shot with the kind of cool, supremely elegant detachment you find in a Dutch still life reminding us we must all die.

I think of May Ray when I encounter the work of Chinese artist Zhang Enli. I think of the American Surrealist in passing when I see Zhang’s huge paintings of packages tied with string, and then later, because Zhang’s work evokes a genuinely disquieting sense of beauty and dislocation, as I sit in a prison-like box made of plywood whose interior is painted with swirling clouds of colour – muted dirty greens and blue tones. I also think of striking pairings both within Zhang’s own paintings, and as his work appears alongside the photographs of Alex Van Gelder, who takes pictures of blood and animal viscera, all carefully arranged and beautifully shot with the kind of cool, supremely elegant detachment you find in a Dutch still life reminding us we must all die.

The swirling marks on the walls of Zhang’s prison-like box with its single lightbulb are, by an uncomplicated process of association, reminiscent of blood, or perhaps excrement, smeared on the walls of a cell (that's even before I see any of Gelder’s work in the north wing of the gallery). The paint is thinly applied in gestures that follow the sweeping arc of an arm, and you can still see the flimsy wood beneath the thin paint. Since it doesn’t emit a neon glow that makes your skin turn a death-pallor green, or create mind-warping optical illusions (as walk-through boxes in contemporary art increasingly do in their attempt to provide a complete body-shock experience), Zhang’s box is a place of calm, a place where your mind is free to roam expansively, and isn’t simply a conduit for high-octane stimulus. It’s a cell where you might wish to sit in contemplation for a while, with your own random thoughts and projections.

Outside the box, one finds Zhang’s paintings also have a kind of rangy spaciousness to them. They are huge, and he seems obsessed by ropes, nets and mysterious trussed-up packages, like the ones in The Box (above left) and The Package. One smaller painting is called Melancholy (pictured right), but before I look at the title I look at the painting for a long time. It features two balls, one big beach ball in white and yellow, the other a smaller black ball that looks like dense, heavy matter (whether it's much smaller or simply further away is difficult to tell). One thinks of a threatening presence, small but full of menacing intent, waiting, knowing that the bigger ball is just a big softy who is easily deflated.

Outside the box, one finds Zhang’s paintings also have a kind of rangy spaciousness to them. They are huge, and he seems obsessed by ropes, nets and mysterious trussed-up packages, like the ones in The Box (above left) and The Package. One smaller painting is called Melancholy (pictured right), but before I look at the title I look at the painting for a long time. It features two balls, one big beach ball in white and yellow, the other a smaller black ball that looks like dense, heavy matter (whether it's much smaller or simply further away is difficult to tell). One thinks of a threatening presence, small but full of menacing intent, waiting, knowing that the bigger ball is just a big softy who is easily deflated.

These paintings speak in common metaphors, and attempting to describe them in detail means that humour begins to creep in, because there’s a kind of obviousness to them. Any apparent sincerity in expression must, you feel, be underpinned by knowing humour. But that’s the trouble with unpicking metaphors until they unravel like the string on a package whose content is a mystery. The mystery dies. It’s a problem with description generally (and titles, too) and not, you feel, with these paintings themselves. And it’s also a problem to do with our expectations of so much contemporary Western art, which this isn’t. These paintings retain their own mysterious integrity.

In the north gallery, Gelder’s beautifully composed high-definition photographs are both compelling and repellent. The photographs were taken in an outdoor abattoir in Benin, but there is no context here, no suggestion of the noise, the heat, the stink, the physical actuality of place. It’s just viscera, glistening membrane, teeth, eyeballs, tongue, rolls of skin separated from flesh and bone, jawbone, and bits that look like fine cuts for the cooking pot. (Pictured left: Meat Portrait #013, 2012.) On one wall a series of photographs feature a bird's-eye view of bowls of frothy, viscous blood. Rather than slop, these shallow "votive" bowls suggest sacrificial offerings. Such is their coolly non-contexualised framing.

In the north gallery, Gelder’s beautifully composed high-definition photographs are both compelling and repellent. The photographs were taken in an outdoor abattoir in Benin, but there is no context here, no suggestion of the noise, the heat, the stink, the physical actuality of place. It’s just viscera, glistening membrane, teeth, eyeballs, tongue, rolls of skin separated from flesh and bone, jawbone, and bits that look like fine cuts for the cooking pot. (Pictured left: Meat Portrait #013, 2012.) On one wall a series of photographs feature a bird's-eye view of bowls of frothy, viscous blood. Rather than slop, these shallow "votive" bowls suggest sacrificial offerings. Such is their coolly non-contexualised framing.

Gelder used to be a painter, and has a classical painter’s eye and a sense of art history. One particularly affecting image, different from all the rest, shows a perfectly formed calf foetus (main picture), its skin smooth and sheeny like pink opal, but already attracting flies. Here too is a powerfully disquieting evocation of beauty and dislocation.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment