I began work on Where My Feet Fall a few months into the pandemic of 2020. After lockdown was announced we all became better walkers, and the collection took on greater resonance.

The writers I selected were invited to do one of two things – recall a past journey or go on a new one. Not only did they willingly set off, but I discovered that many were skilled snappers, mappers and sketchers, or their families were. Vivid images would be added to their words, and here is a sneak preview of five of them.

“Lost” by Joanna Kavenna

The wind howled. I was asleep when someone tugged at my foot. I half-woke, assumed it was a dream. Black sky, celestial dust. I couldn’t actually be sleeping in the depths of nowhere, alone. Then I heard a loud, definite rustling and then – worse – the sound of footsteps. Suddenly I was awake and very frightened. “Who’s there?” I said, stupidly. “What do you want?” I said all sorts of stupid things and then with a desperate, trembling movement, I switched on the torch. I expected – a murderer, a pale lunatic, a moon spirit, the ghost of my father. Instead – sheep! I was so angry with them, for scaring the hell out of me. But they looked miserable, with their little white faces. Like a Greek chorus, masked and anxious. I had stolen their bed. It was the only sheltered place for miles around. “I’m sorry,” I said, still trembling from the shock. “I’m only here for a night.” They stared at me, balefully. “Why not settle down over there?” I said – gesturing towards the opposite wall. It wasn’t as sheltered but it was better than nothing. For a while the sheep stood around, then by some mysterious consensus they gave up and wandered off. I switched off the torch, my heart still pounding. What a ridiculous scene! It took a while before I slept, if timorously, and when I woke again at dawn the sheep had vanished. I hoped they’d had a decent night.

I expected – a murderer, a pale lunatic, a moon spirit, the ghost of my father. Instead – sheep! I was so angry with them, for scaring the hell out of me. But they looked miserable, with their little white faces. Like a Greek chorus, masked and anxious. I had stolen their bed. It was the only sheltered place for miles around. “I’m sorry,” I said, still trembling from the shock. “I’m only here for a night.” They stared at me, balefully. “Why not settle down over there?” I said – gesturing towards the opposite wall. It wasn’t as sheltered but it was better than nothing. For a while the sheep stood around, then by some mysterious consensus they gave up and wandered off. I switched off the torch, my heart still pounding. What a ridiculous scene! It took a while before I slept, if timorously, and when I woke again at dawn the sheep had vanished. I hoped they’d had a decent night.

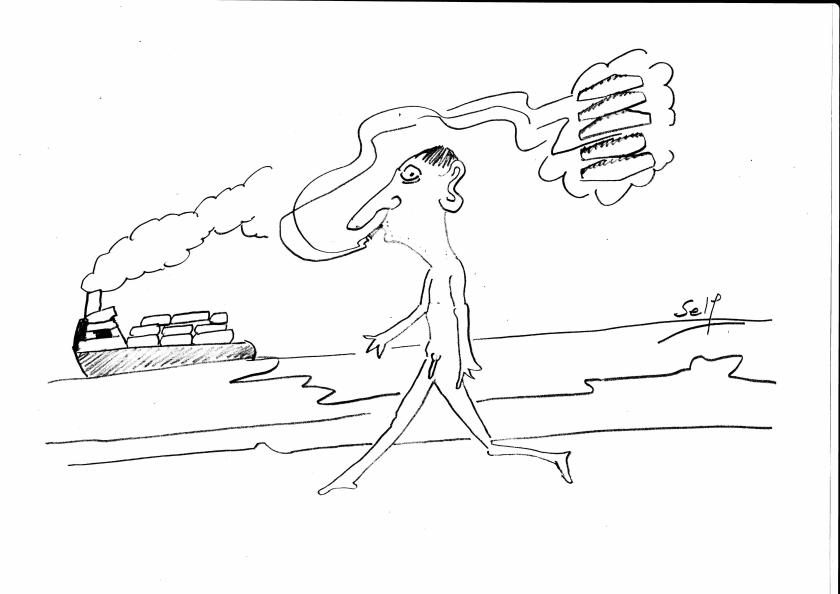

“Grain ... Again” by Will Self

“Grain ... Again” by Will Self

To my sleepless and sore mind, late at night, I apply this balm: a vision in which I am always either walking to the Isle of Grain, or am already standing on its whale-backed and scrubby immensity, staring out across the Thames Estuary. I'm poised in my mind's eye, feeling the breeze salt-smack my face and the exhaling warmth of a sun that's settling itself down definitively to the rear, to the west, and in the past ... The cats’ paws scratching the glaucous waters drag my eyes across the estuary to the smudged line of Southend’s mile-long pier – then beyond it, to the low smear of Foulness Island. There’s no sign from this distance of the Broomway – the ancient track across the tidal flats, formed by bundles of the shrub sunk in the mud; but then it’s almost impossible to see it when you’re standing right on the evanescent thing, confused by this great wet-streaked plain, stretching upstream to where the chimneys of the flare-stack at the Coryton oil refinery on Canvey Island form the real eastern gateway to that city which Marlow, the protagonist of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, describes as “one of the dark places of the earth”.

“Even Greater Kailash (and Parts of Conoor)” by Keshava Guha

The nonpareil act of dog-lover sadism is the import into Delhi of St Bernards and Alaskan Malamutes, and their cousin the Siberian Husky. They spend the summer, if they are lucky, in air-conditioned prison. To see them out on summer walks is to truly understand the cruelty that can call itself love.

In the winter, despite the air, they revive. I am thinking in particular of one Husky, who lives with his sister in B block, home of GK’s grandest houses, the kind of place where it is no surprise to find a Husky next to a Porsche. All winter they spend their days loosely tied to two trees outside their gate, accompanied by two minders. The sister ignores me; he always sees me coming, and by the time I reach him he is ready. Few hugs are properly fifty-fifty. There is usually, on balance, one hugger and one hugged, and most of us gravitate to one of these roles. This Husky, whose sadistic owners I have never met and whose names I do not know, is a hugger. By the time I reach him he is up on his hind legs, and a second later two paws press tightly against my lower back. For over a year, during the pandemic of 2020, he was the only thing I hugged.

Few hugs are properly fifty-fifty. There is usually, on balance, one hugger and one hugged, and most of us gravitate to one of these roles. This Husky, whose sadistic owners I have never met and whose names I do not know, is a hugger. By the time I reach him he is up on his hind legs, and a second later two paws press tightly against my lower back. For over a year, during the pandemic of 2020, he was the only thing I hugged.

“A Curvy Road Is Better Than a Straight One” by Sally Bayley

At the top of the road cross the wide avenue; watch for dawdling cars: an elderly gentleman in his Ford Cortina. Off to pick up his prescription at the chemist, no doubt – he waves – why do old people wave so much when they should be driving? Turn right and you’re on Maltravers Drive. The road is widening and the houses turning all leafy and ivy; red creeper around the windows and wisteria up the walls. Nothing too bare and open, nothing too much on show. Is that a woman at the window? I can’t tell. Her curtains are drawn. Only the postman and gasman, or someone with a very particular reason, would dare to ring the bell.

The pavement slabs are wide here, wide enough to let dog walkers by. Dog walkers are a suspicious breed; they stand around between the trees looking shifty, making a right old mess beneath the leaves. “Doesn’t bear thinking about,” says Mrs Braithwaite to Miss Cull, the music teacher. “The amount of dog doo-da in that little wood.” Miss Cull looks anxious – someone might overhear them – ladies don’t talk about dog doo-da, especially not at lunchtime.

The pavement slabs are wide here, wide enough to let dog walkers by. Dog walkers are a suspicious breed; they stand around between the trees looking shifty, making a right old mess beneath the leaves. “Doesn’t bear thinking about,” says Mrs Braithwaite to Miss Cull, the music teacher. “The amount of dog doo-da in that little wood.” Miss Cull looks anxious – someone might overhear them – ladies don’t talk about dog doo-da, especially not at lunchtime.

I spy Mrs Braithwaite on her bicycle turning down the road. She comes home at lunchtime to feed her birds – “Budgies make an awful din, and Percy and Henry are chatty little gentlemen. Around twelve o’clock they begin to duel. If I leave them until the end of the day, they’ll have pecked one another’s eyes out.” Henry and Percy don’t seem very polite to me, but Mrs Braithwaite is an odd sort of person; she speaks in quaint ways. She sees me and waves, in that stiff cardboardy way, like the Queen.

“Portals” by Agnès Poirier

To be born a Parisian is to be born a compulsive walker. The specific geography and demographics of Paris – one of the most densely populated cities in the world, with around 53,000 inhabitants per square mile – make the city a permanent beehive where one is never alone. Every street has its artisan bakery, butcher, greengrocer, bank, independent bookshop, café, wine bar, bistro and patisserie. For any budding or young walker, this is a reassuring feeling. Later in life, Parisians may aspire to more calm and less promiscuity. However, their world views will have been shaped by this togetherness, and more often than not by this communion of spirit.

If the constant proximity feels claustrophobic, there are always Parisian cemeteries, havens of perfect balance between solitude and intimacy – only with ghosts. All in all, an attractive proposition for curious teenagers. Aged fifteen, I had a routine with my friend Laure. Once a week, during an unusually long lunch break at school, we would take a sandwich with us and roam Paris looking for mysterious places. I was the chubby blonde, she the lean brunette, and we were both strong on research. We were on a quest for singular and romantic places and the choice of our weekly excursion was based on thorough preparation.

On another very cold and snowy December day, we headed excitedly towards Passage d’Enfer (“Hell’s Passage”) in the fourteenth arrondissement. And from there we made our way to Montparnasse Cemetery and its main gates on Boulevard Edgar Quinet. The place was almost deserted, and with the fresh and unusually thick snow under our feet, we felt we were walking on cotton wool. The strange lack of footsteps, the striking black and white contrast between the blinding white of the snow- covered graves and their dark grey edges, not to mention the freezing air, impressed our young minds. We had drawn up a list of the souls we wanted to pay a visit to. Laure did not want to miss the tombs of Jean Seberg, Guy de Maupassant and Man Ray. And I, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Baudelaire. A carved oval headstone on Man Ray’s grave read “unconcerned but not indifferent” in English. My friend and I, intrigued, tried to pierce the subtext of those four words and we soon forgot about everything else. The expression remained a private joke between us for years. And to this day, I don’t quite know what we really meant when we knowingly uttered the phrase, other than a sign of solidarity.

On another very cold and snowy December day, we headed excitedly towards Passage d’Enfer (“Hell’s Passage”) in the fourteenth arrondissement. And from there we made our way to Montparnasse Cemetery and its main gates on Boulevard Edgar Quinet. The place was almost deserted, and with the fresh and unusually thick snow under our feet, we felt we were walking on cotton wool. The strange lack of footsteps, the striking black and white contrast between the blinding white of the snow- covered graves and their dark grey edges, not to mention the freezing air, impressed our young minds. We had drawn up a list of the souls we wanted to pay a visit to. Laure did not want to miss the tombs of Jean Seberg, Guy de Maupassant and Man Ray. And I, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre and Baudelaire. A carved oval headstone on Man Ray’s grave read “unconcerned but not indifferent” in English. My friend and I, intrigued, tried to pierce the subtext of those four words and we soon forgot about everything else. The expression remained a private joke between us for years. And to this day, I don’t quite know what we really meant when we knowingly uttered the phrase, other than a sign of solidarity.

- Where My Feet Fall: Going For A Walk in Twenty Stories edited by Duncan Minshull (William Collins, £18.99)

- More book reviews and features on theartsdesk

Credits: sheep image by Blythe Kavenna, path image by Arizona Smith

Add comment