Frances Larson: Undreamed Shores review - journeys without maps | reviews, news & interviews

Frances Larson: Undreamed Shores review - journeys without maps

Frances Larson: Undreamed Shores review - journeys without maps

How the first female anthropologists found freedom far from home

Beatrice Blackwood had lived in a clifftop village between surf and jungle on Bougainville Island, part of the Solomon archipelago in the South Pacific. She hunted, fished and grew crops with local people as she studied their social and sexual lives; she joined the men on risky forays into other communities “that had never seen a white person before, but she never recorded any animosity from them”. Later, in 1936, she relocated to the remote interior of New Guinea.

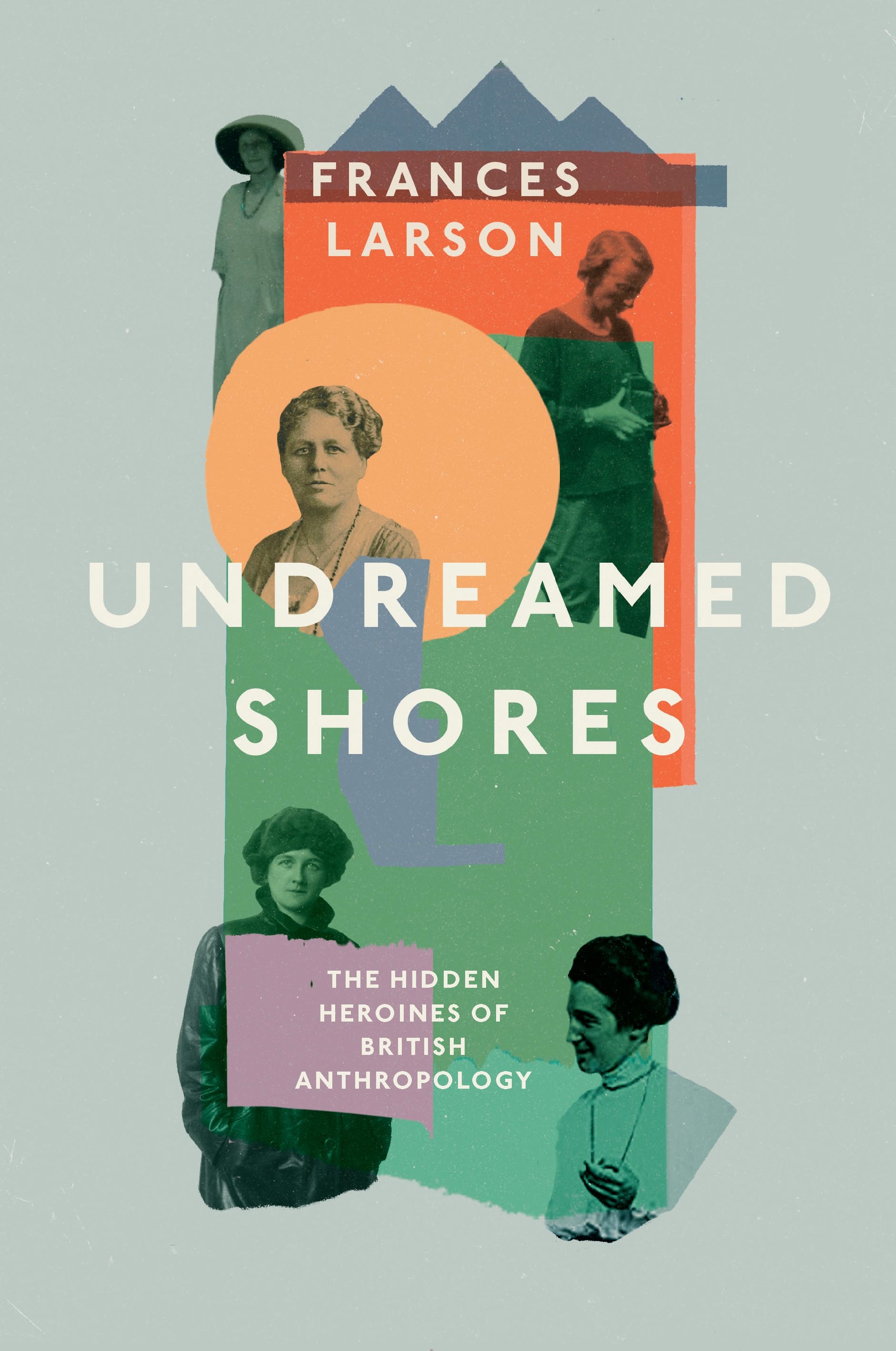

One day, however, Blackwood had the chance to demonstrate a New Guinea “bulllroarer” – a ceremonial musical instrument. In the yard behind the museum, this “tiny figure” swung the blade of the humming device ecstatically around her head, dancing until she looked as if “she might have risen vertically like a helicopter”. The bullroarer, Frances Larson drily notes, had “discharged deep energies inside her”. Where did those energies come from that took her from Oxford to New Guinea and the Solomons (pictured below: White Island, Bougainville, by Jeremy Weate), and where did they finally go? Several single and group biographies have lately sought to rescue path-breaking female scholars of the early 20th century from the ignorance or condescension of posterity. To a degree, Larson’s follows this route in her group portrait of five anthropologists all linked by Oxford University’s diploma in anthropology, and by the Pitt Rivers Museum, in the years before, during and after the First World War. Her subjects were all “intellectual pioneers” in a fledgling discipline, who as women “faced entrenched prejudice and constraint at every turn”. Yet anthropology, as Larson makes clear, has from its outset operated on the fringes of academic power – an art, and science, of fuzzy edges, porous boundaries and dissolving categories. That ambiguity enriches her book.

Several single and group biographies have lately sought to rescue path-breaking female scholars of the early 20th century from the ignorance or condescension of posterity. To a degree, Larson’s follows this route in her group portrait of five anthropologists all linked by Oxford University’s diploma in anthropology, and by the Pitt Rivers Museum, in the years before, during and after the First World War. Her subjects were all “intellectual pioneers” in a fledgling discipline, who as women “faced entrenched prejudice and constraint at every turn”. Yet anthropology, as Larson makes clear, has from its outset operated on the fringes of academic power – an art, and science, of fuzzy edges, porous boundaries and dissolving categories. That ambiguity enriches her book.

Undreamed Shores captivates, fascinates and haunts because these five women, all extraordinary in various ways, could never quite fit into the approved narrative mandated by attitudes today – a fable of struggle against sexist odds crowned by eventual success, to a soundtrack of glass ceilings cracking, and the grudging applause of bewhiskered patriarchs. Certainly, these women – Beatrice Blackwood, Katherine Routledge, Maria Czaplicka, Barbara Freire-Marreco and Winifred Blackman – fought against stupid and grotesque obstacles to the exercise of their talents. All excelled at “being an interloper”, in Oxford University as much as the Pacific, Egypt or Siberia. They wrote acclaimed books and carved out territories of achievement at a time when even the few women graduates who barged open the door into intellectual professions were expected to be “peripheral, clerical and grateful”. All found forms of freedom and fulfilment on their distant shores.

Each, though, complicates the textbook trajectory with a twisting story of her own. Those stories tell of mighty global forces as much as of deep personal impulses. The women joined a discipline in its Oxford infancy, steered by a handful of refugees from other fields who themselves had little solid grounding for their work. These few innovators, above all Robert Marett, Henry Balfour and Arthur Thomson, in fact proved unusually encouraging to women students. Between 1907 and 1918, 27 women (including Larson’s five subjects) and 103 men registered for the Oxford anthropology diploma – at that period, a notably high proportion. In this case, the barriers to professional recognition did not chiefly lurk in the group’s own, fragile and insecure, institutional backyard.

Anthropology, besides, was still a marginal discipline. It had no choice but to foreground the relationship between subject and object, researcher and community. That exchange introduced an endemic uncertainty. Not even the alpha male of this era – Bronisław Malinowski, whose shadow falls over this book – could intellectually conquer “his” Trobriand Islanders as a mountaineer conquers a peak. Intensive fieldwork, which Malinowski made the gold standard for research, remained a “fleeting and fragmentary” enterprise, always compromised and always incomplete. Meanwhile, “human culture was infinitely various, but the resources available for studying it were slim.” These conditions drastically rationed the stock of glittering prizes and clear-cut triumphs.

Routledge, eldest of the five, came from a Darlington family of mine owners. Born to command, she carried an endowment of class, and colonial, privilege first to East Africa, where she studied the Kikuyu, then to Easter Island, where she conducted outstanding research on the people and their history. The blessings and drawbacks of “colonial infrastructure” recurs as a motif in Larson’s book. For all her lavish funds and memsahib manners, however, Routledge faced growing resentment from her husband Scoresby – a surly companion, and shameless thief of her achievements. Routledge bravely faced down rebellious Easter Islanders. She could not overcome the legalistic malice of her spouse. After their marriage foundered, he seized her house and – as in some Wilkie Collins novel – even had her committed to a genteel private asylum. This happened in 1929, not 1829. From an anthropological point of view, nothing in her Pacific adventures rivals the barbaric absurdity of her confinement, until death in 1935, in this “closed, secret and sinister world”. It was Ticehurst House in Sussex that harboured the heart of patriarchal darkness.  Daughter of a Polish station-master, Maria Czaplicka emerges as the most intrepid, glamorous and – ultimately – tragic member of Larson’s group. As a Pole born under Tsarist rule, she belonged to a colonised, not colonising, culture. She never lost the gift of observing the dynamics of power from below. Supremely capable of every practical and intellectual task, she too had a troublesome male companion in tow – the American chancer Henry Hall – but seems to have needed his presence nonetheless. With Hall and two other women, then with Hall alone, she studied nomadic Siberian reindeer herders in 1914-1915. Often frozen, feverish, snowbound and wind-battered, hundreds of miles from any settlement, she found “a sense of ecstasy that blotted out pain”. (Pictured above: reindeer herders in Yamal, Siberia, 1975, by Victor Zagumyannov.) Czaplicka returned alive. Her book, My Siberian Year, made waves (“3,000 Miles by Sledge in Siberia”). Money and jobs, though, proved elusive – as for every other woman except the privately wealthy Routledge. She flourished in First World War Oxford, a place “increasingly, and very successfully, run by women”, and became the university’s first full-time female lecturer. But lack of high-level support thwarted her plans. In 1921, in Bristol, where she had held another temporary post, she took her own life aged 36, after learning that she had been passed over for a travelling fellowship. Marett, her mentor, wrote that she “struck fire out of whatever she touched”.

Daughter of a Polish station-master, Maria Czaplicka emerges as the most intrepid, glamorous and – ultimately – tragic member of Larson’s group. As a Pole born under Tsarist rule, she belonged to a colonised, not colonising, culture. She never lost the gift of observing the dynamics of power from below. Supremely capable of every practical and intellectual task, she too had a troublesome male companion in tow – the American chancer Henry Hall – but seems to have needed his presence nonetheless. With Hall and two other women, then with Hall alone, she studied nomadic Siberian reindeer herders in 1914-1915. Often frozen, feverish, snowbound and wind-battered, hundreds of miles from any settlement, she found “a sense of ecstasy that blotted out pain”. (Pictured above: reindeer herders in Yamal, Siberia, 1975, by Victor Zagumyannov.) Czaplicka returned alive. Her book, My Siberian Year, made waves (“3,000 Miles by Sledge in Siberia”). Money and jobs, though, proved elusive – as for every other woman except the privately wealthy Routledge. She flourished in First World War Oxford, a place “increasingly, and very successfully, run by women”, and became the university’s first full-time female lecturer. But lack of high-level support thwarted her plans. In 1921, in Bristol, where she had held another temporary post, she took her own life aged 36, after learning that she had been passed over for a travelling fellowship. Marett, her mentor, wrote that she “struck fire out of whatever she touched”.

Larson’s two other first-generation anthropologists followed more predictable paths for their era – of promise and ambition curtailed from within, by a sense of family duty and obligation, as well as from without. Barbara Freire-Marreco undertook breakthrough studies of indigenous peoples in New Mexico and Arizona during the pre-Great War years. She won an Oxford fellowship, worked in wartime intelligence, and entertained the offer of a plumb US lectureship – but “her parents took precedence”. Soon after, she married a Scottish mathematician and settled into a long, placid and outwardly contented life in Hampshire. She sometimes wrote poems that remembered the American Southwest; in one, she dreams of her past and wakes “unsatisfied to English day”.

The daughter of a happy clan in a Norfolk rectory, Winifred Blackman tried more systematically to balance her commitments at home and far away. She fell in love with Egypt and explored the living culture of the fellahin while male colleagues kept their gaze firmly on mummies underneath the sand. Thanks in part to medical magnate Henry Wellcome, Blackman was able to return to her beloved country for 20 seasons, until the Second World War. She not only studied the people but purchased artefacts, as did other of Larson’s subjects – here the darker side of early anthropology creeps in, as plunder or extraction. Blackman won respect but could not escape the backdrop of semi-colonial power. Her devoted assistant, Hideyb, was murdered in 1923, possibly because of his close links with the Englishwoman. When her brother and fellow-Egyptologist, Aylward, got a chair in Liverpool, she and her siblings dutifully followed him. Although hailed in Egypt as Sheikha Shifa, Lady of Healing, she never did publish her book on traditional medicine.

The daughter of a happy clan in a Norfolk rectory, Winifred Blackman tried more systematically to balance her commitments at home and far away. She fell in love with Egypt and explored the living culture of the fellahin while male colleagues kept their gaze firmly on mummies underneath the sand. Thanks in part to medical magnate Henry Wellcome, Blackman was able to return to her beloved country for 20 seasons, until the Second World War. She not only studied the people but purchased artefacts, as did other of Larson’s subjects – here the darker side of early anthropology creeps in, as plunder or extraction. Blackman won respect but could not escape the backdrop of semi-colonial power. Her devoted assistant, Hideyb, was murdered in 1923, possibly because of his close links with the Englishwoman. When her brother and fellow-Egyptologist, Aylward, got a chair in Liverpool, she and her siblings dutifully followed him. Although hailed in Egypt as Sheikha Shifa, Lady of Healing, she never did publish her book on traditional medicine.

Anthropology can show us that the myths cultures tell about themselves sit uneasily alongside the mess, drift and doubt of actual ways of life. So, in a way, does Undreamed Shores. Larson’s heroines did challenge stereotypes, break chains, surmount obstacles and do great deeds. To each tale, though, clings a penumbra of mixed motives, cross purposes, unfinished business – largely, for sure, owing to the “prejudice and paranoia” of the times about high-achieving women, but also thanks to interference from forces that ranged from the geopolitics of the age to the unruly needs of multi-dimensional individuals. Some of the doubt stems, too, from the “element of artifice in the anthropological endeavour” itself, which Beatrice Blackwood recognised. Reality will always escape, even undermine, the paradigmatic story you pursue. Larson’s close and sensitive attention to that reality gives this book, superbly researched and winningly written, its compassionate authority as well as its story-telling zest. It offers few standing ovations; but plenty of loose ends, lost threads and closed doors. Yet we never lose sight of why these quests mattered, and what they gave the seekers. As Larson writes about Winifred Blackman, “Egypt made her happy”.

- Undreamed Shores: The Hidden Heroines of British Anthropology by Frances Larson (Granta, £20)

- Boyd Tonkin has been awarded the 2020 Benson Medal of the Royal Society of Literature

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - Pulp Diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment