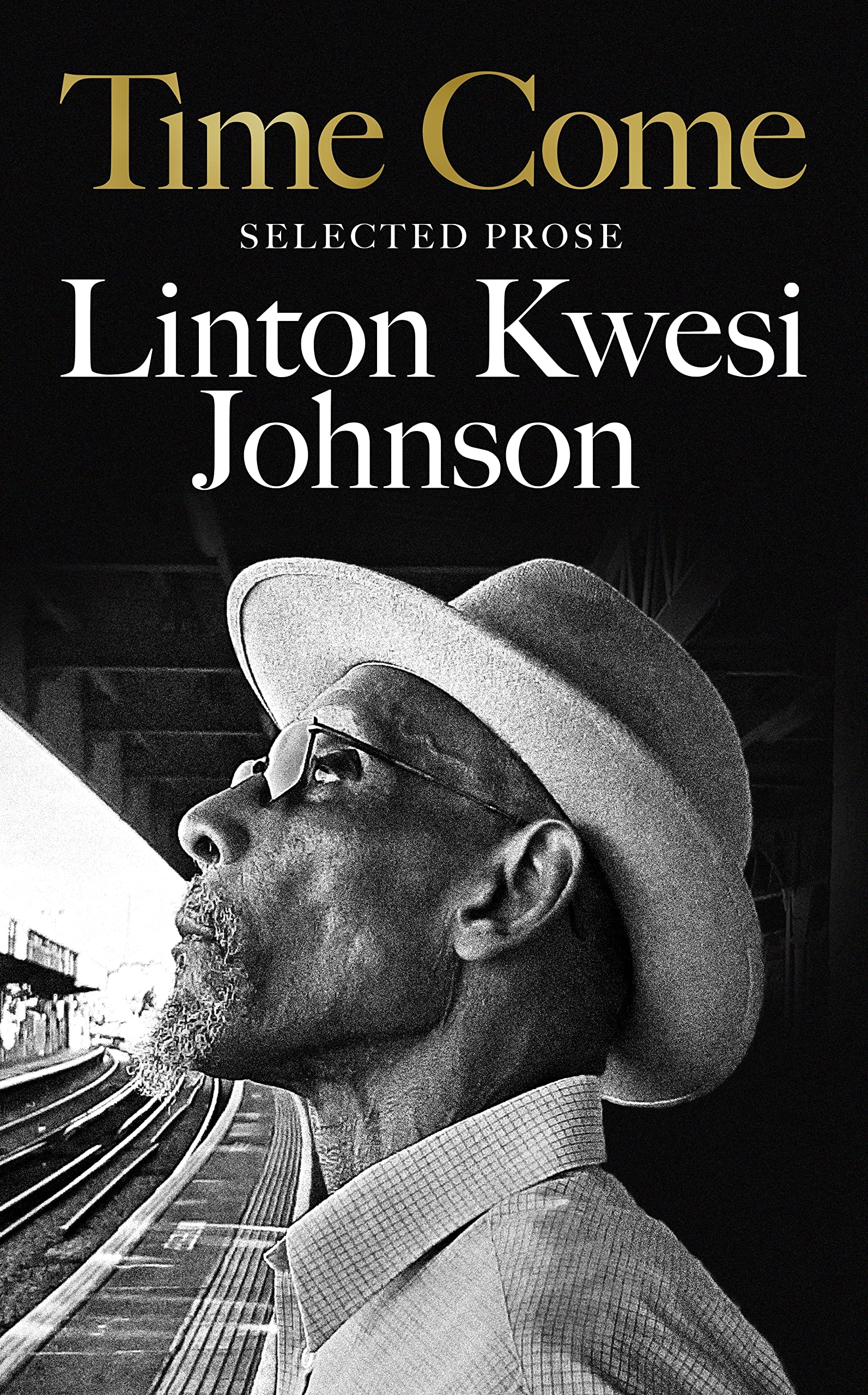

Straight-backed at 70, Linton Kwesi Johnson wears the smart garb of a British Caribbean elder – trilby, cream jacket, West Indies maroon jumper and tie, grey trousers, blue socks and grey shoes. His voice has resonant, slow-rolling authority befitting Britain’s pioneer, premier dub poet. He folds his legs, but raises a lecturing finger. Though relatively relaxed and ready to laugh, he shows, in attitude as much as posture, a stern, iron backbone.

Marking his prose collection Time Come’s publication, LKJ has sold out the grand Theatre Royal for this talk and selection of laptop-played tracks with Brighton Festival guest director Nabihah Iqbal. Iqbal is an empathetic and quick-witted compere, half Johnson’s age but bridging any generational divide, and quietly drawing on her own experience as a British Pakistani musician, writer, artist and activist growing up after Johnson’s embattled black Britons.

“Soon I’ll be 70,” Johnson recalls thinking, explaining Time Come’s genesis. “Next thing you know I’ll be dead.” So he pondered a posthumous selection of record and film reviews, essays and profiles written between his art. “My wife said, ‘Don’t be an idiot. The time is now…’”

“Soon I’ll be 70,” Johnson recalls thinking, explaining Time Come’s genesis. “Next thing you know I’ll be dead.” So he pondered a posthumous selection of record and film reviews, essays and profiles written between his art. “My wife said, ‘Don’t be an idiot. The time is now…’”

His account of his early life is educative, changed by Brixton Library, New Beacon Books and conversations in its founder John La Rose’s Finsbury Park front room, the Black Panthers and the collection Black Poetry. WEB Du Bois’ The Souls of Black Folk (1903) “awakened something in me”. The Sixties civil rights and anti-colonial struggles forged him in their “cooling embers”.

“Jamaican folk culture” was his “bedrock”, though, in his first 11 years with “peasant” parents before moving to England in 1962. The King James Bible was his first lexicon alongside his grandmother’s folk songs, spirituals and riddles, told on rustic “moonlit nights”.

Britain was a “racially hostile…rude awakening”, Jamaican music’s “lyricism” a crucial comfort. Prince Buster’s “talking tunes” hit first, and Johnson selects “Ten Commandments” - “Very chauvinistic, but let’s hear it” – and “Judge Dread”, a laptop and the theatre’s sound-system doing neither any favours. By the Seventies, he was a “reggae purist”, “serious, serious student” and lone dissenter at Bob Marley’s rise above the other Wailers. “You’ve taken the mixed-race one and made [him] a star” and “dreadlocked exotic”, he thought and wrote, which sounds more heretical now. As for Island marketing Marley as “king of rock?” “What the hell? I was disgusted.” Marley later met him and talked deeply.

Poetry, politics and music was interwoven. Johnson became a reggae star on Island himself, with his dub poetry accompanied by Dennis Bovell. “License Fi Kill” (1998) is the only track he lets run nearly to the end, as it names the black dead in Met Police custody and blames the law’s limp guardians, as a harmonica wails. A rare recent poem written in lockdown portrays “a magical day of exuberant light” in Brockwell Park during 2020’s eerily blissful spring, shadowed by ambulance cries.

Poetry, politics and music was interwoven. Johnson became a reggae star on Island himself, with his dub poetry accompanied by Dennis Bovell. “License Fi Kill” (1998) is the only track he lets run nearly to the end, as it names the black dead in Met Police custody and blames the law’s limp guardians, as a harmonica wails. A rare recent poem written in lockdown portrays “a magical day of exuberant light” in Brockwell Park during 2020’s eerily blissful spring, shadowed by ambulance cries.

During audience questions, the notion that he’s “the godfather of UK hip-hop” has him looking dismissively over his shoulder, the idea of recommending new grime artists absurd. “I’m an old man now!” he snorts, suggesting Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. He talks knowledgably, anyway, of hip-hop and British-African grime’s Jamaican roots, and won’t let Iqbal’s suggestion of grime and reggae’s similar “ethos” pass, noting the latter’s spiritual and African, Rastafari consciousness.

Asked for the difference between black British experience in his youth and now, he acknowledges today’s subtler, ongoing struggle. Still, his generation was “outside British society”. Through “self-organisation, riots and insurrections”, they moved inside. “We fought. And we won.”

Add comment