When the first volume of Estonian master Jaan Kross’s peerless historical trilogy first appeared in an English translation by Merike Lepasaar Beecher back in 2016, what leapt out at me about this fictionalised saga about the adventures of real-life chronicler Balthasar Russow was how much it had in common with the Thomas Cromwell of Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall.

Like Cromwell, Russow came from humble stock – though whether the peasantry into which he was born was Estonian-speaking, as Kross assumes, is open to question – and rose to mingle with aristocracy and royalty, a thorn in the side of many German lords in his home city of Tallinn. I’d argue that Kross’s portrait is just as rich and complex. And yet The Ropewalker, Volume One of Kross’s Between Three Plagues trilogy, didn’t take off in the UK. Volumes Two and Three have gone straight to paperback, and as with Mantel’s last instalment, a long time elapsed (in this case six years) before the final instalment appeared. This is a shame, because anyone who reads the opening chapter of the trilogy, a vividly drawn scene which gives that volume its title, will be hooked.

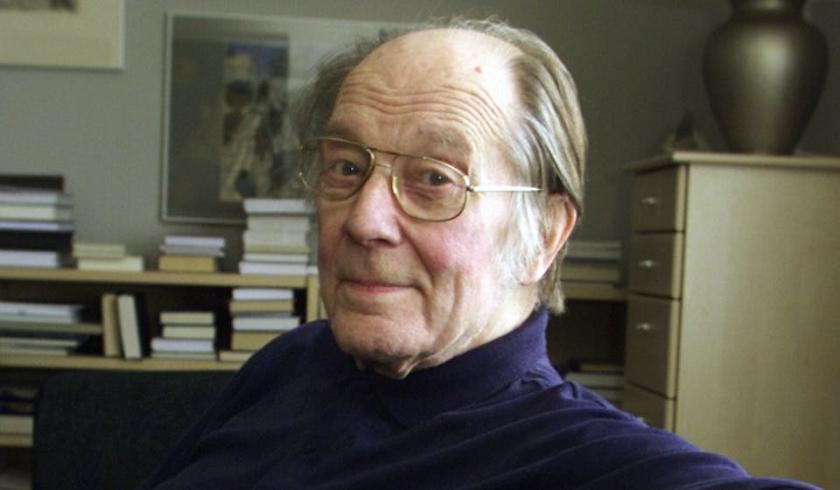

It says much for the clarity and memorability of Kross’s treatment that the grand finale’s often elliptical reference back to previous events didn’t have me wondering what I’d forgotten that had led to the consequences cited here. In any case Tallinn from 1578 to 1600, the year of Russow’s death, is so vividly conjured as the joint main character of A Book of Falsehoods that one lives in every vivid moment. Russow’s Chronicle of Livonia proves as successful in the city as it has been in Rostock and Bremen. But its rocking of the status quo provokes spite and obstruction from the overlords, as well as some Machiavellian dealings from the Swedish royalty that moves in once the Russians have been routed. There is an extra layer of significance in that Kross, who died in 2007, spent eight years in Soviet captivity and decades more under Soviet rule, knew well the prevarications and viciousnesses of Soviet party meetings in the Estonia he lived to see free of Russian rule. The historical novel was an ideal way of using what Beecher calls ‘Aesopian writing’ to outwit the censor.

It says much for the clarity and memorability of Kross’s treatment that the grand finale’s often elliptical reference back to previous events didn’t have me wondering what I’d forgotten that had led to the consequences cited here. In any case Tallinn from 1578 to 1600, the year of Russow’s death, is so vividly conjured as the joint main character of A Book of Falsehoods that one lives in every vivid moment. Russow’s Chronicle of Livonia proves as successful in the city as it has been in Rostock and Bremen. But its rocking of the status quo provokes spite and obstruction from the overlords, as well as some Machiavellian dealings from the Swedish royalty that moves in once the Russians have been routed. There is an extra layer of significance in that Kross, who died in 2007, spent eight years in Soviet captivity and decades more under Soviet rule, knew well the prevarications and viciousnesses of Soviet party meetings in the Estonia he lived to see free of Russian rule. The historical novel was an ideal way of using what Beecher calls ‘Aesopian writing’ to outwit the censor.

Religious imbroglios are threader through the tale by virtue of Russow's post as Lutheran pastor of the Estonian congregation at the Church of the Holy Spirit, which still boasts the most beautiful interior in Tallinn. And his private life is no less vividly evoked than his public struggles. Kross is ruthlessly objective and spare when plague takes many of those closest to his protagonist, and acute, too, on the dynamics of envy and jealousy. As in Mantel’s masterpiece (in her case, only three times one of many), everyone in this world comes vividly to life. May the publication of this final volume finally be the cue for many around the world to welcome Kross as one of the great novelists of any age, as so many Estonians already do.

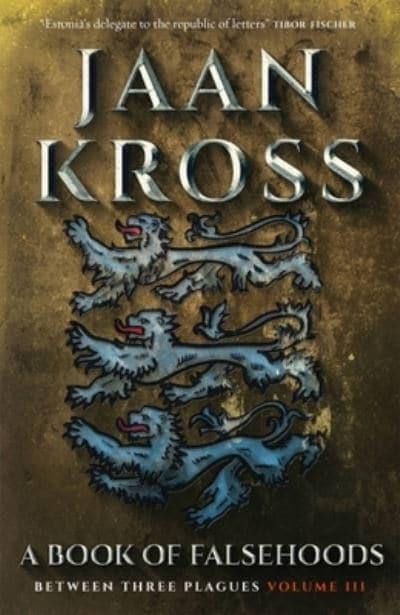

- A Book of Falsehoods by Jaan Kross, tr. Merike Lepasaar Beecher (MacLehose Press, 2022, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment