From his debut Metroland, right up to the Man Booker-winning The Sense of an Ending, the prospect of a road not taken has haunted the mild and mediocre narrators of Julian Barnes’s novels. Like Tony Webster in The Sense of an Ending, “average at life; average at truth; morally average”, they tend to prefer, or at least settle for, a comfy seat in the stalls as life’s high dramas unfold in front of them. True, the novels often shatter this detachment and, with gentle ruthlessness, wreck their hard-won equipoise. Yet The Only Story, although it initially slips into the well-woven tweed of the Barnes first-person voice, does venture from the start down that other, riskier track. Here, the bruised confessions come from a protagonist who did take the plunge, go for broke, burn his boats.

As before, Barnes gives us a story-teller who looks back in sorrow, perplexity, but not quite regret, on the follies and fantasies of youth. In this case, however, the artist of memory – not so much “unreliable”, perhaps, as incurably ambivalent about the past – has not watched timidly from the stands. He has played, and lost, on the Centre Court of love. In the mid-1960s, at the Surrey tennis club near his parents’ dreary commuter-belt home, the 19-year-old student Paul meets the married, much older Susan Macleod. He is whiling away his summer vacation; she is whiling away her life. Barnes, of course, would never merely serve up a reheated version of The Graduate, with Mrs Macleod a Home Counties spit of Mris Robinson. Young Paul assumes that their thrillingly unorthodox affair defies every cougar-toyboy stereotype, although the sadder-wiser narrator knows that all lovers cherish the “illusion” that “they escape both category and description”. Bound in wedlock to the epically dull Gordon (a civil servant, naturally), Susan entrances Paul with her free spirit, her mischief and merriment. She “laughs at life” and mocks the chains that bind her.

Stolen trysts in the marital home, naughty jaunts in a green Morris Minor, and a delicious drizzle of rumour and outrage in “the Village”, turn their liaison into a suburban “transgressive” idyll. Gordon, Paul’s parents, the entire tennis club: all sort-of know, or at least suspect. As always, Barnes relishes the English bourgeois dance of euphemism, innuendo and knowing silence. However, Paul has fallen in love. So, more ominously, has Susan.

For him, “First love fixes a life for ever”; probably (although young Paul fails to grasp this) for her as well. Largely through her lonely, tipsy and fearless pal Joan (for whom, now, “nothing fucking matters”), we hear of Susan’s pre-Gordon boyfriends, lost to war and illness. Susan feels her becalmed life with Gordon and two daughters as a disenchanted aftermath, with her part of a "played-out generation”. Barnes never overstates the clash of her post-war weariness against Paul’s callow idealism, Sixties-style. Still, it raises yet another barrier between them.

Despite every obstacle, this shocking couple refuse to part and return to age-appropriate sexual behaviour. To local consternation, they abscond to live together in south London – courtesy of Susan’s “running-away fund”. An adulterous summer dalliance across the nets and behind the curtains deepens into full-blown, life-defining scandal. Paul shares his hopeful generation’s belief in true, convention-busting love and “how it can transform a life, indeed the lives of two people”. Susan’s demons, which her teenaged swain has understandably failed to spot, will test that faith to and beyond the brink of destruction.

In Barnes’s second act, Paul’s confident first person yields to the urgent, anguished second. “You” discover the heavy baggage your married lover has carried with her from Surrey. Hints of childhood abuse by a sleazy uncle; not only emotional but physical violence from the stolid, seething Gordon; the secret drinking that dulls these and other hidden pains: Susan, the “damaged free spirit”, has buried her misery underneath a breezy, sexy mask. There’s “a question of shame at the bottom” of her woes.

In their ramshackle love-nest, her drinking descends into florid alcoholic self-harm and self-delusion. Paul, by now a law student and later a solicitor, grasps that his chivalric “rescue” of this tormented woman from her secrecy-ridden home might have worsened her injuries. For all Gordon’s boorishness and sporadic brutality, he, and Susan’s daughters, prove hard to abandon. “You” have falsely thought that “chunks could be cleanly amputated from a life without pain and complication”.

Inevitably, this will end badly. As the pair’s “co-dependency” takes hold, Barnes shows with discreet insight how the ordeal of caring for someone imprisoned in mental suffering may trigger “your own version of panic and pandemonium”. Susan’s “wild, shifting weather of the soul” can still brighten into joy, and wit, and love. But, stroke by stroke, the “wild graffiti of booze” – and the past events that have scribbled that graffiti – defaces her personality. In ambulance calls and psychiatric wards, Paul’s all-consuming passion frays into “pity and anger”.

After this second-act frenzy, harrowing but never melodramatic, the novel in its last phase withdraws into a more distant, meditative mood. A sense of anticlimax sometimes hovers over these passages of rueful memoir and wistful aphorism as Paul looks back on love, and loss. Now, the cooler third person supplants the second: “he” has retired from love’s dangerous game to survive, in familiar Barnes fashion, as a semi-detached spectator. “He knew the contentment of feeling less. His emotional life was recast as a social life.” Bureaucratic jobs abroad give Paul a handy pretext for avoiding commitment, followed in retirement by a cosy hiding-place at an artisan produce business in rural Somerset. Blessed are the cheese-makers, as the younger Paul might well have noted.

After this second-act frenzy, harrowing but never melodramatic, the novel in its last phase withdraws into a more distant, meditative mood. A sense of anticlimax sometimes hovers over these passages of rueful memoir and wistful aphorism as Paul looks back on love, and loss. Now, the cooler third person supplants the second: “he” has retired from love’s dangerous game to survive, in familiar Barnes fashion, as a semi-detached spectator. “He knew the contentment of feeling less. His emotional life was recast as a social life.” Bureaucratic jobs abroad give Paul a handy pretext for avoiding commitment, followed in retirement by a cosy hiding-place at an artisan produce business in rural Somerset. Blessed are the cheese-makers, as the younger Paul might well have noted.

Once so vital a spark, Susan fades into the background. “The remnant of her” waits for death while Paul discourses on the nature of love and the “constantly changing” truths of memory. He can be a sententious bore. We miss her. That’s the point: ecstatic, catastrophic love has stranded Paul (Joan’s phrase) among the “walking wounded”. A cushioned half-life helps to salve those wounds. “Comforting words like redemption and closure” hardly apply. “Cauterization”, the fate of Paul’s emotions, does.

Something precious departs from this quietly heart-rending novel in its final act – as if a Barnes story could only come to rest within a comfort-zone of post-traumatic elegy. Nerdishly, Paul collects literary reflections on love without recording their source. He approves of one that goes: “in my opinion, every love, happy or unhappy, is a real disaster once you give yourself over to it entirely”. Borrowed from Turgenev’s play A Month in the Country, that maxim actually appears in Barnes’s short story, The Revival. Turgenev’s hero, Rakitin, goes on to bemoan the “shame and agony”, the “enslavement and infection”, of being “owned” by the woman one loves. The Only Story never quite allows Susan, and her splendidly ruinous desire, to “own” it. Some readers might wish that she did. But Barnes, like Paul, is "trying to tell you the truth". At that time, just as in some 19th-century novel of adultery, the woman bore most of its cost. That meant, after notoriety, invisibility.

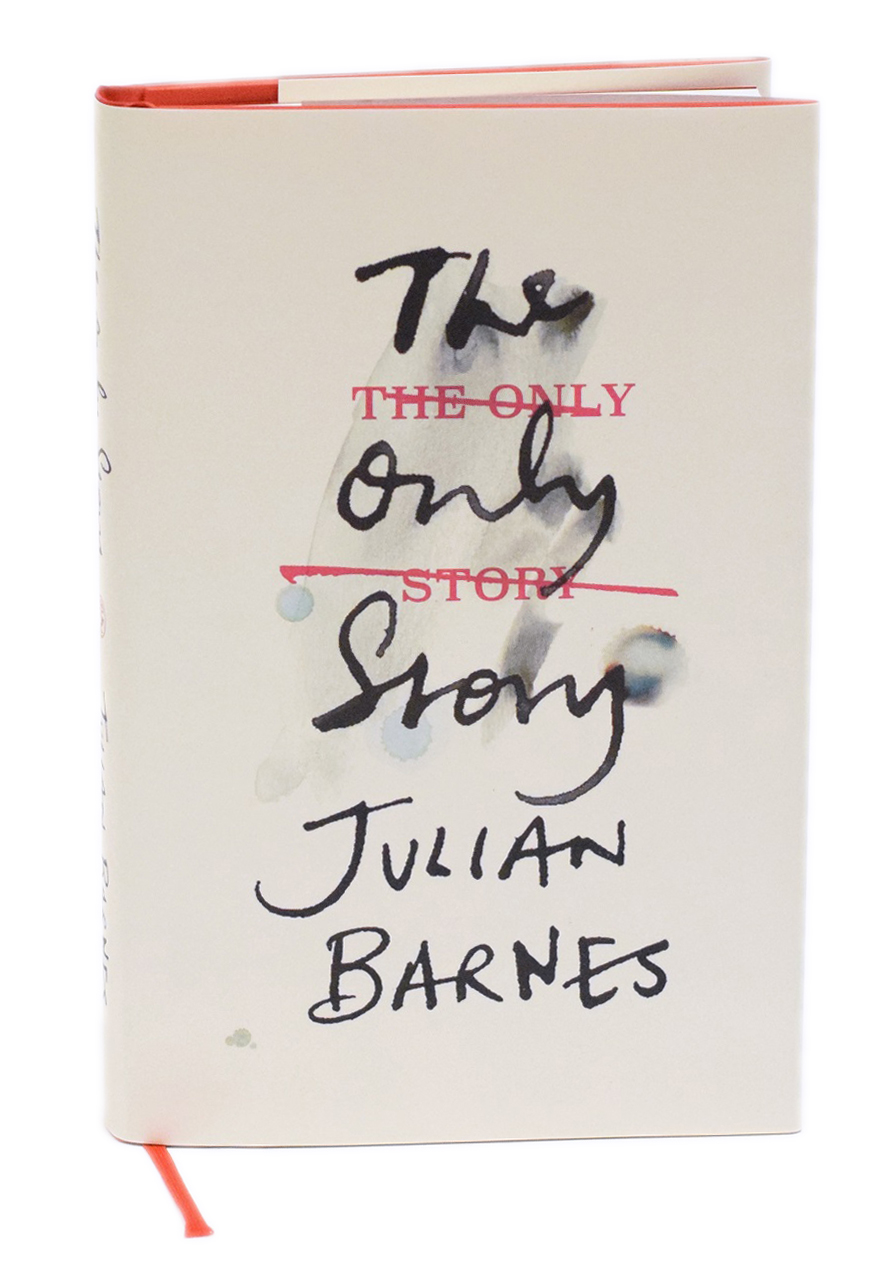

- The Only Story by Julian Barnes (Jonathan Cape, £16.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment