Karl Ove Knausgaard: So Much Longing in So Little Space review – smiles more than screams | reviews, news & interviews

Karl Ove Knausgaard: So Much Longing in So Little Space review – smiles more than screams

Karl Ove Knausgaard: So Much Longing in So Little Space review – smiles more than screams

Norway's epic self-analyst paints a refreshingly ego-free portrait of Munch

Around the works canteen, a dozen huge wall-paintings depict, in bright cheerful colours spread across radically stylised forms, happy scenes of women and men at work and play beside a sunlit sea. They till, pick, dance, chat, dream, wander or water flowers.

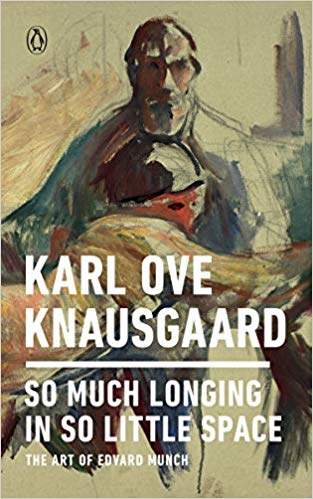

Painted by Edvard Munch in 1922 after a commission from an idealistic tycoon, the heart-lifting frieze that runs around the lunch room at the Freia chocolate factory in Oslo isn’t normally open to visitors and does not figure in Knausgaard’s wholly absorbing book about Munch’s art. I was lucky enough to see it during the eye-opening surveys of the Norwegian artist’s prolific output that, in 2013, marked the 150th anniversary of his birth. Yet, as Knausgaard shows, art of this kind that registers and celebrates ordinary joy and toil, and that “tends to his immediate world” almost as “a form of cosmology or caretaking”, is fairly typical of Munch. Over the 65 years of his active career, it vastly outweighs the comparatively brief spasm of Symbolist anguish in the 1890s that gave us “The Scream”, “The Vampire”, “Jealousy”, “Evening on Karl Johan Street” and those other “iconic” images that have devoured his legacy ever since. In fact, between the 1880s and the 1940s (he died in 1944 and, in a calculated snub to the Nazi-controlled wartime puppet regime, left his works not to the Norwegian state but to the City of Oslo), Munch returned repeatedly to the same motifs. Although his repertoire of images may persist, their meaning often changes drastically. Even the serene Freia cycle enlists themes familiar from those too-famous paintings of solitude, terror and yearning that made up his 1890s “Frieze of Life”. Knausgaard (pictured below by Sam Barker) often notes how much of Munch’s art turns on “seriality”, repetition with variation, but not solely as a neurotic return to sites of grief and trauma (though, certainly, that impulse drives him too: witness the various versions of “The Scream”). Multiple iterations also serve him as a way to capture time, art, and life itself, as a “work in progress”, and to revisit that ever-changing “fluid zone between the world in itself and our image of it”.  So Much Longing in So Little Space – which has its roots in an exhibition that Knausgaard curated at Oslo’s Munch Museum in 2017 – succeeds on its own terms as a searching, shrewd and jargon-free interpretation of the artist’s art and life. Knausgaard writes clearly and candidly, as a fellow-pilgrim partnering the reader through Munch’s inner landscape rather than a preacher or teacher. Ingvild Burkey’s fine translation carries that unpretentious intimacy into English with total assurance. Knausgaard is aware of the weight of scholarship that presses down on Munch, but keen also to respect not just his own more idiosyncratic insights but those of other artists he consults. They include painters Anselm Kiefer and Vanessa Baird, photographer Stephen Gill, and film-maker Joachim Trier.

So Much Longing in So Little Space – which has its roots in an exhibition that Knausgaard curated at Oslo’s Munch Museum in 2017 – succeeds on its own terms as a searching, shrewd and jargon-free interpretation of the artist’s art and life. Knausgaard writes clearly and candidly, as a fellow-pilgrim partnering the reader through Munch’s inner landscape rather than a preacher or teacher. Ingvild Burkey’s fine translation carries that unpretentious intimacy into English with total assurance. Knausgaard is aware of the weight of scholarship that presses down on Munch, but keen also to respect not just his own more idiosyncratic insights but those of other artists he consults. They include painters Anselm Kiefer and Vanessa Baird, photographer Stephen Gill, and film-maker Joachim Trier.

Still, every potential reader will know that he’s not just another critic but a global literary phenomenon. His own work (above all, in the six-volume confessional “auto-fictions” of My Struggle) has branded him as the most celebrated Norwegian virtuoso of private agony and ecstasy to flourish on the world cultural stage since – well, Edvard Munch himself. All credit to this celebrity self-analyst, then, for not transforming his Munch study into another offcut slice of semi-disguised autobiography. For sure, he slips in some dryly comic Knausgaardian episodes. He feels acute “shame and anxiety” when he worries that sneery Munch experts think he has chosen duds from the vaults as the centrepieces for his Oslo show; he tells us about the sitcom snags of a trip back from southern Sweden to Norway to lecture on the artist; traces the suspense of his online bidding war at an auction site for a genuine Munch print (when his house and children need some much more basic purchases); or sets the stage for his interviews as a magazine profile-writer would. And, inevitably, he does use his ideas about Munch as a means to hammer out a sort of personal manifesto for the processes and purposes of art that has integrity. It “lives by transgressing boundaries”, must free itself from “doubt and shame” in order to thrive, may sanctify everyday human existence but, equally, must sometimes dissolve the noisy self to honour “the separate reality of things”. All of which we might expect from the author of My Struggle: which, in spite of its reputation as a narcisstic epic, is not principally an ego-fest but a mission to escape from selfhood too.

So Knausgaard looks at Munch much as, in his reading, Munch looks at the world. Yes, he paints himself into the scene, as a hesitant, even bumbling, figure plunged into the roiling waters of art theory, and gallery politics, far outside his comfort zone. At the same time, he does try to get out of the way of the art and to practise the same creative “self-effacement” that he finds and likes in Munch.

So Knausgaard looks at Munch much as, in his reading, Munch looks at the world. Yes, he paints himself into the scene, as a hesitant, even bumbling, figure plunged into the roiling waters of art theory, and gallery politics, far outside his comfort zone. At the same time, he does try to get out of the way of the art and to practise the same creative “self-effacement” that he finds and likes in Munch.

The best artworks, he argues, balance “a great openness to the world” with the ability “to bring out one’s own vision”. Hence his nagging uneasiness with those youthful “Scream”-era landmarks painted by the tormented “iconographer of strangeness”, so subjective yet (as he acknowledges) oddly universal. In contrast, Knausgaard directs his gaze mostly onto lesser-known and later paintings – of Munch’s sister Inger, a cabbage field, an elm forest, a winter night, a house-painter on a ladder – that count as “still uncanonised, still undecided”. He loves the modest, workmanlike artisan-painter who, as a youngish man, passed thorough the kind of existential crisis that killed Van Gogh, lived past eighty, and created 1,789 paintings in addition to a huge array of graphic works. Knausgaard salutes the restless ageing artist who succeeded in “breaking down all notions of his own greatness” to craft free-form compositions, often consciously sketchy or “imperfect”, but imbued with “the joy of living, humour and a faint undercurrent of melancholy”. Surprisingly, at least for those art-lovers who have encountered only the febrile Munch of myth rather the artist Knausgaard sees, he discovers a thoroughly workaday visionary: one who invokes not merely, or not mostly, the drama of the solitary self but “the presence of the world on the world’s terms”. Meeting Knausgaard’s dogged, inspired grafter makes you glad and grateful that the screaming had to stop.

- So Much Longing in So Little Space: the art of Edvard Munch by Karl Ove Knausgaard, translated by Ingvild Burkey (Harvill Secker, £16.99)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Help to give theartsdesk a future!

Support our GoFundMe appeal

Add comment