Sharon Dolin: Hitchcock Blonde: A Cinematic Memoir review - a poet’s life filtered through Hitchcock’s lens | reviews, news & interviews

Sharon Dolin: Hitchcock Blonde: A Cinematic Memoir review - a poet’s life filtered through Hitchcock’s lens

Sharon Dolin: Hitchcock Blonde: A Cinematic Memoir review - a poet’s life filtered through Hitchcock’s lens

Life imitates art in a memoir that struggles to lead a life of its own

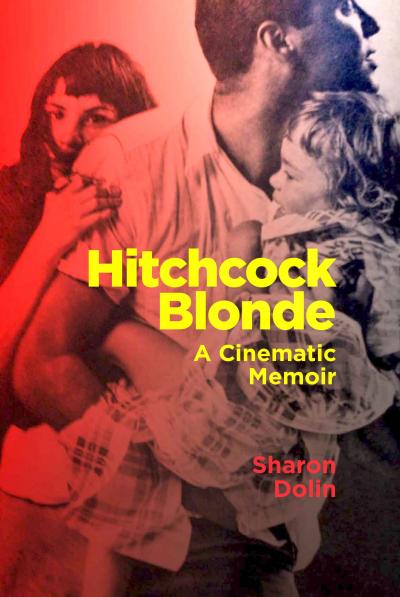

Poet Sharon Dolin’s memoir Hitchcock Blonde ends (no spoilers) in the same way as the famous English director’s Vertigo begins: with a cliffhanger. Of sorts.

This show-stopping stunt is symptomatic of the sort of relationship Dolin claims to have had with Hitchcock throughout her life. She has found herself in situations resembling those in his films, on which she was weaned from an early age, often watching the flicks while sandwiched between her parents on their marital bed. It’s an appropriately Freudian image for a writer and a book so well attuned to those films’ obsession with desire, danger, death and the irrational life of the mind. These preoccupations seem to be as much Dolin’s as they are Hitchcock’s, and just as they were as much Hitchcock’s as they are his characters’.

Like Hitchcock, too, Dolin is constantly questioning whether the narrative she traces is as simple as it seems. She recognises the element of fabrication in any attempt to present the past. “I am the director behind the camera each time I conjure up and reconstruct a scene”, she admits. This shadow of doubt does not stop her, though, from insisting on a certain amount of natural chemistry between her stories and the films’, which can prove hard work at times. There are points when she drops the juggling act altogether, which is just as well, because it leads to her to draw some less than convincing parallels.

In other hands, someone like Geoff Dyer, Hitchcock Blonde might have turned into one of those “successful books about failure”: making good out of a project gone wrong. Dolin does have some misgivings about hers – “Am I giving my experience greater depth and nuance this way? Or am I distorting the view?” – but her self-awareness is not quite enough to make up for the shortcomings. Overall, the performance feels a little bit too earnest for that. This is her life, after all. She can only play around with it so much.

The book’s first half is dedicated to Dolin’s childhood and adolescence, defined by downward mobility, body dysmorphia and a dysfunctional marriage. Rewatching Rear Window, set in 1950s Brooklyn, she comes to consider the relationship between the travelling salesman and bedridden wife, spied on by the photographer with the broken leg (James Stewart again), as a “darker version” of her parents’ own.

The correspondence is fairly uncanny, as far it goes: Dolin was raised, or mis-raised as she sees it, in an overlooked Brooklyn apartment in the 60s and 70s by a travelling salesman (moustachioed “Irv, the funky father”) and a heavily sedated college dropout (“Sellie”). The comparison feels fruitful until Dolin begins to press it. “Like Jeff in Rear Window, my mother had broken her leg”, which leads her to recount that episode. So, wait – who’s who now?

If she occasionally overcomplicates, seeing too much in the films, Dolin can also oversimplify, seeing too little. In the second part, she premises the story of her talent for finding and sticking with mendacious men – two lying, cheating husbands, one abusive fiancé and a few other unfortunate flings – on the films Spellbound and To Catch A Thief, which she dilutes to being about two women who just won’t give up on damaged or distrustful love interests.

Viewed from a certain angle, these narratives are there, but the idea risks robbing them of their character, their defining characteristics, as it does her biography. When she compares the leading man in To Catch A Thief with her first husband, it does not seem to matter that the former was an American ex-cat burglar, pretending to be a American tourist on the French Riviera, while the latter was an ex-acrobat pretending to be an Italian (who was actually Spanish), holidaying on the Catalan coast.

The waiving of details is a shame because Dolin is at her best when she hones in on them, producing some interesting idiosyncratic readings, like when she notices the strangely unquestioned age difference between Stewart and Grace Kelly in Rear Window, or the almost Shakespearian need for “ocular proof” in The Lady Vanishes, or how Madeleine, the femme fatale in Vertigo, is the namesake of the cake that sent Proust’s memory into overdrive. This sort of attention can enliven Dolin’s memories, too, particularly the meditation on her first marriage which she writes in Barcelona (she tells us) where her duplicitous, thieving first husband Carlos was from. It is one of the best passages in the book, as well as one of the longest stretches without reference to Hitchcock. At one point, Dolin watches a soap bubble artist blow “more and more elaborate yet transitory shapes … whose skin catches the multicoloured lights” in a city square. As she does this, she is reminded of “the kind of beautiful, yet ultimately illusory, world I had tried to create for myself with Carlos.” Dolin started “writing these memories, aided by Hitchcock, in order to give shape” to her life, but here is one (of many) memories, suggestive and fanciful but emerging from tangible, living detail. Just like they do in the movies.

Strangely, in embarking on this project, it feels as if Dolin has stepped into a peculiarly Hitchcockian trap. Trying to fit into or being made to fit into ready-made moulds or archetypes often proves foolish, if not fatal for nearly all of his leading ladies, that infamous string of peroxide-blonde blondes (whom Hitchcock cast because, in his own words, they made “the best victims”). Zoom in closer, dig a little deeper, his films seem to say, and you find that what you thought was a perfect match, in fact, was not. Of course, we never do – not until it is too late.

- Hitchcock Blonde: A Cinematic Memoir by Sharon Dolin (Terra Nova Press, $26.95)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment