Colourise London Choral Sinfonia/Michael Waldron, with Roderick Williams (baritone), Andrew Staples (tenor), Elena Urioste (violin) (Orchid)

Colourise London Choral Sinfonia/Michael Waldron, with Roderick Williams (baritone), Andrew Staples (tenor), Elena Urioste (violin) (Orchid)

Colourise, the latest album from by the London Choral Sinfonia, proved revelatory: I came for the Vaughan Williams, but got unexpectedly drawn in by the Lennox Berkeley. His Variations on a Hymn by Orlando Gibbons gets its premiere recording and is a piece I am very pleased to know: it grows engagingly from a humble beginning, solo strings quietly mimicking viols, before growing to fill its 19-minute duration without feeling a moment too long. Commissioned for the 1952 Aldeburgh Festival, the Variations subsequently disappeared – perhaps because of a substandard performance. This is a shame, as it is a great find by Michael Waldron, the musical director of the LCS. Tenor Andrew Staples stands in for Peter Pears in a charming solo section – there is also a spot for organist James Orford. But the true heroes are the choir, featuring a crack squad of choral voices, and if the Berkeley is unlikely to get many more performances (not least because of its instrumentation) it is very good to have it out there.

Even the more familiar Vaughan Williams is heard in unfamiliar garb. The Five Mystical Songs were premiered at the Three Choirs Festival in 1911 for solo voice, choir and orchestra but is most commonly heard for solo voice and piano (there are also other instrumentations). This recording is yet another, an arrangement made by the composer for solo voice (the incomparable Roderick Williams), choir, string orchestra and piano. This makes for a wonderful start to the disc as the choir piles up a glorious chord on “Rise heart; thy Lord is risen” – but the moments of choral grandeur don’t preclude some wonderfully intimate moments. There is no better enunciator of a text than Williams, who persuades with every note he sings. The rest of the disc has a vigorous and colourful Capriol Suite (which, as Michael Waldron says in his excellent liner notes, is not actually very well represented in the catalogue) and the version of The Lark Ascending in Paul Drayton’s arrangement for solo violin and choir. Here, violinist Elena Urioste floats above a bed of sustained harmonies provided by choir in place of the usual strings, completing a delightfully familiar-cum-unfamiliar album. - Bernard Hughes

Céline Moinet: Lumière – Works by Poulenc, Ravel, Debussy, Saint-Saëns Céline Moinet (oboe and cor anglais), Florian Uhlig (piano), Sophie Dervaux (bassoon) (Berlin Classics)

Céline Moinet: Lumière – Works by Poulenc, Ravel, Debussy, Saint-Saëns Céline Moinet (oboe and cor anglais), Florian Uhlig (piano), Sophie Dervaux (bassoon) (Berlin Classics)

This record of French music for oboe/piano duo and oboe/bassoon/piano trio reached me late and by a round-about route, but is worth a visit for the glorious playing from two French-born wind players, both of whom have principals’ chairs in top-flight orchestras in the German-speaking world... orchestras which, coincidentally and for historical reasons, happen also to function as the orchestras of their cities' respective opera houses. Céline Moinet has been principal oboe of the Dresdner Staatskapelle since 2007, appointed at the age of 23; Sophie Dervaux was appointed principal bassoon of the Wiener Philharmoniker at the age of 24 in 2015. I was tempted to conjecture whether these opera duties make their wonderfully lyrical playing more natural...but that’s probably a slightly pointless case of “I can see it works in practice...but does it work in theory?”. Wind playing at this level speaks for itself.

A highlight is definitely Moinet and Dervaux’s superb account of Poulenc’s lively, witty 1924-26 Trio for oboe, bassoon and piano, with the fine pianist Florian Uhlig. The work was dedicated to De Falla, and the young Poulenc received advice he valued to help him complete it from Stravinsky. This great recording of the piece is as persuasively idiomatic as any on record. Pure joy. We are altogether in a more attractive sound-world than, say, with Pascal Rogé/ Maurice Bourgue/Amaury Wallez. I was also completely persuaded by the balance, the rightness, the honesty of Moinet and Uhlig's Saint-Saëns oboe sonata. There's more feeling than empty bravura and speed, and it really works. Moinet's cor anglais playing in Debussy's saxophone "Rhapsodie" (arranged) has fireside warmth. On the other hand I know I will be going back far less often to a curious Schmitt/Riou arrangement of Ravel’s Le Tombeau de Couperin, based on the composer's partial orchestration of 1919. In fact it sent me straight back to the utterly irreplaceable delights of Vlado Perlmuter’s 1973 solo piano reading. With the possible exception of that well-intentioned near-miss, this is a very recommendable record. Céline Moinet has said that the album represents “my truth, my honest interpretation of French music as a Frenchwoman'', a sentiment which rings very true. Beautifully recorded too. - Sebastian Scotney

Andy Akiho: Seven Pillars Sandbox Percussion (AKI Rhythm Productions)

Andy Akiho: Seven Pillars Sandbox Percussion (AKI Rhythm Productions)

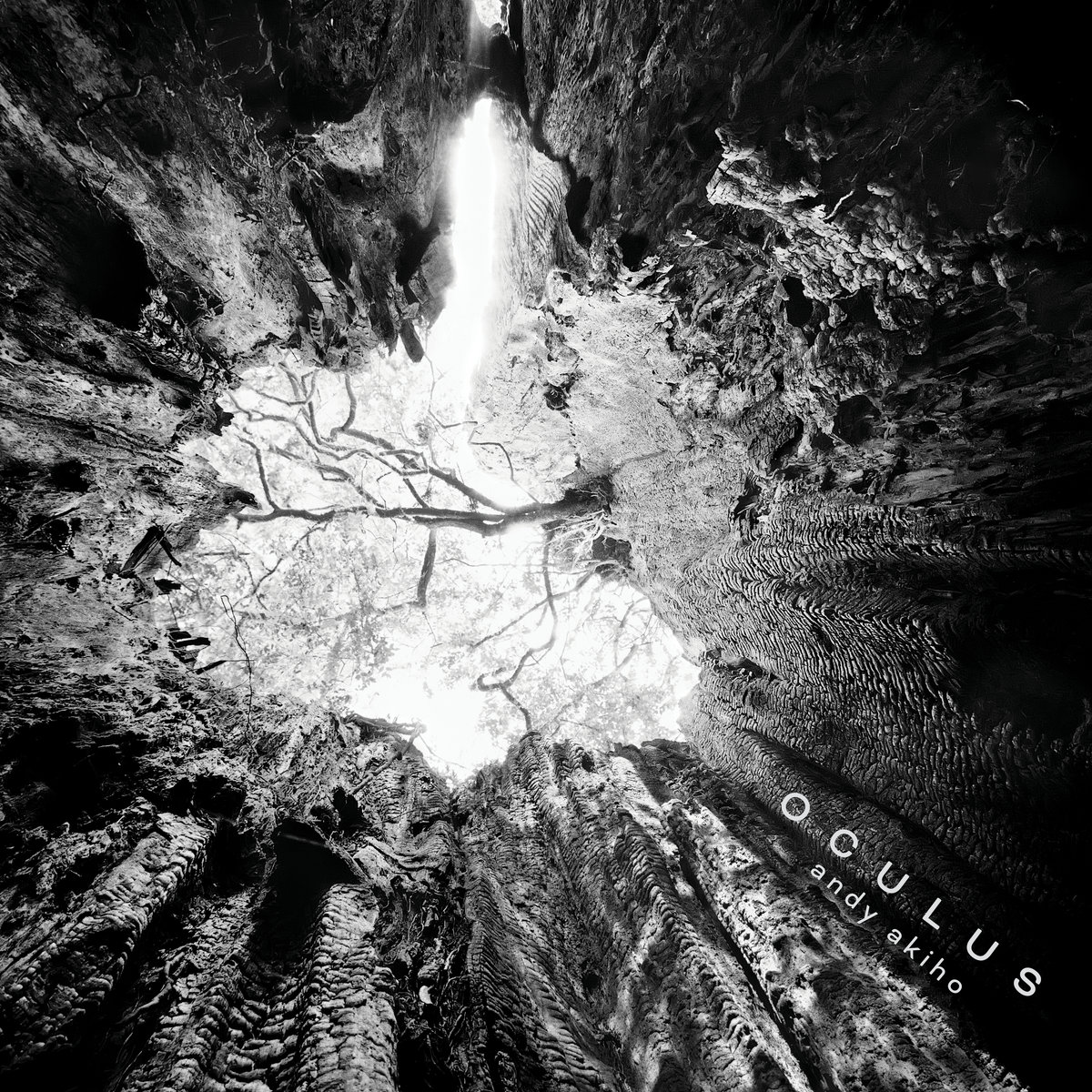

Oculus (AKI Rhythm Productions)

Two discs of music by American contemporary composer Andy Akiho have caught my ear in recent months. Born in 1979, his biography states that “he spent most of his 20s playing steel pan by ear in Trinidad and began composing at 28,” the physicality and theatricality involved in playing steel pans an essential element of Akiho’s music. Have a look at “Pillar IV” from the vast percussion piece Seven Pillars on YouTube; watching three members of Brooklyn’s Sandbox Percussion in action (look out for the wine bottles) is absorbing. Seven Pillars is a huge, eleven-movement opus, written for Sandbox between 2018 and 2019, and described by one of the group as “the culminating project of our first decade as an ensemble.” “Pillar IV”, was conceived first as a standalone work, Akiho later adding six more quartet movements and interspersing them with solo sections, each one introducing a new instrument that becomes part of the ensemble.

Buy the physical album and you'll be bowled over by the elaborate presentation, the individual movements introduced by Akiho on a beautiful fold-out sheet full of unexpected creases and cut outs. Don’t try and open it outdoors on a windy day. Packaging apart, this release is a remarkable achievement; my advice would be to clear 80 minutes and listen to the whole thing in a single sitting, marvelling at the players’ collective virtuosity and feats of coordination in the denser sections. The solo movements are enthralling. I especially enjoyed the extended glockenspiel and vibraphone numbers, and who wouldn't want to hear what a bowed marimba sounds like? “Cartograph”, the tenth movement, is stunning. Find the YouTube performance and look out for how Victor Caccese manages to play the bass drum while standing a metre away from it, almost oblivious to what’s happening around him. This is as much high-end sport as music making. An extraordinary, unclassifiable work, and the recording captures every tiny detail.

Photographer Stuart Rome’s haunting photographs of giant redwood trees prompted Oculus, he and Akiho bonding while working at the American Academy in Rome. Akiho’s five-movement LigNEouS Suite (the word meaning made of or resembling wood) is scored for string quartet and marimba, Sandbox Percussion’s Ian Rosenbaum joining the Dover Quartet in music that’s consolatory and violent by turns, the beautiful Bartokian night-music of “LigNEouS IV” rebuffed by the driving rhythms and irregular accents of the final movement. Deciduous is a duet for violinist Kristin Lee and Akiho on steel pan, Akiho making two seemingly incompatible voices sing together. Who’d have thought that a steel pan could be played with such grace and agility, Akiho’s rippling, harp-like accompaniment allowing Lee to soar above. Speaking Tree features an 11-piece ensemble and was prompted by Akiho’s nocturnal schleps around Princeton, NJ. The musical material was sketched after he’d fallen asleep under a favourite tree in the town’s cemetery. A winning mixture of introspection and exuberance, it’s a beguiling work, with some wonderful writing for chattering trumpets and a doleful tuba. As with Seven Pillars, track down the stylishly-produced physical album, the booklet containing a selection of Rome’s monochrome photographs.

Photographer Stuart Rome’s haunting photographs of giant redwood trees prompted Oculus, he and Akiho bonding while working at the American Academy in Rome. Akiho’s five-movement LigNEouS Suite (the word meaning made of or resembling wood) is scored for string quartet and marimba, Sandbox Percussion’s Ian Rosenbaum joining the Dover Quartet in music that’s consolatory and violent by turns, the beautiful Bartokian night-music of “LigNEouS IV” rebuffed by the driving rhythms and irregular accents of the final movement. Deciduous is a duet for violinist Kristin Lee and Akiho on steel pan, Akiho making two seemingly incompatible voices sing together. Who’d have thought that a steel pan could be played with such grace and agility, Akiho’s rippling, harp-like accompaniment allowing Lee to soar above. Speaking Tree features an 11-piece ensemble and was prompted by Akiho’s nocturnal schleps around Princeton, NJ. The musical material was sketched after he’d fallen asleep under a favourite tree in the town’s cemetery. A winning mixture of introspection and exuberance, it’s a beguiling work, with some wonderful writing for chattering trumpets and a doleful tuba. As with Seven Pillars, track down the stylishly-produced physical album, the booklet containing a selection of Rome’s monochrome photographs.

Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde (chamber version arr. Schoenberg and Riehn) Le Balcon/Maxime Pascal, with Stéphane Degout (baritone) and Kévin Amiel (tenor) (B Records)

Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde (chamber version arr. Schoenberg and Riehn) Le Balcon/Maxime Pascal, with Stéphane Degout (baritone) and Kévin Amiel (tenor) (B Records)

I’ve enjoyed scaled-down performances of several Mahler symphonies, particularly Michelle Castelletti’s arrangement of the 10th on BIS; the sparer textures found in Mahler’s late output lose less when arranged for smaller forces. Schoenberg began adapting Das Lied von der Erde for his Society for Private Musical Performances in 1921, the project left unfinished when Austrian hyperinflation forced the group to shut up shop. German composer Rainer Riehn completed the arrangement in the early 1980s, the finished score using just twelve musicians. I miss the orchestral trumpets, particularly the high solo in the “Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde”, but the reduced scoring sounds very idiomatic, conductor Maxime Pascal rightly praising Schoenberg’s talents as an orchestrator and lauding his subtle use of a harmonium. Issues of balance simply don’t arise in this 2020 live performance, tenor Kévin Amiel really taking flight in the first song. Pascal’s Paris-based Le Balcon (named after a Jean Genet play) are magnificent throughout, the solo winds especially impressive. Having baritone Stéphane Degout take on the role usually allotted to an alto works well, his deep, rich voice an ideal match for the lean, bright textures. Pascal brings out the humour in “Von der Jugend”, and the noisy central section of “Von der Schönheit” is a blast.

Degout is outstanding in “Der Abschied”. Mahler’s funereal opening is a real chiller, and pianist Alphonse Celim convincingly impersonates a mandolin in the 3/4 section. The overlapping cross-rhythms are dispatched with flair and the whole-tone scale in the final minutes should induce shivers. The coda, gentle and intimate, is blissful. It’s a winner; if you’ve not heard this arrangement of Das Lied, start here. The acoustic of the Basilique royale de Saint-Denis in Paris is just resonant enough. A word about the packaging; this performance comes in a chunky box. Inside are six separate inserts containing the texts for each song, each adorned with Raphaël Serres’s bonkers but intriguing artwork (“… monsters, trees and architecture inhabit six zones connected by a strange perspective…”), the whole thing included as a foldout poster. You won’t get that with a download.

Sibelius: Orchestral Songs Marianne Beate Kielland (mezzo-soprano), Norwegian Radio Orchestra/Petre Popelka (Lawo Classics)

Sibelius: Orchestral Songs Marianne Beate Kielland (mezzo-soprano), Norwegian Radio Orchestra/Petre Popelka (Lawo Classics)

Sibelius’s symphonies tend to obscure the rest of his output. He was far more prolific than most of us realise; BIS’s highly covetable Sibelius Edition consists of 68 discs spread over 13 volumes. Most of his songs were originally written with piano accompaniment, and this CD contains 18 of them in orchestral garb. Four were rescored by Sibelius himself, the rest by a variety of hands including the composer’s son-in-law Jussi Jalas. You’d never suspect: each song sounding like idiomatic Sibelius. The majority set Swedish texts, though two in the Op. 17 set includes a pair of Finnish songs. Many are like miniature tone poems, the composer’s own arrangements of three of the Opus 38 songs (dating from 1903) pack an incredible punch, the mournful clarinets at the start of “På verandan vid havet” look forward to The Bard and the 4th Symphony, mezzo Marianne Beate Kielland singing of “the melancholic light shining from heaven’s immortal stars… their destiny to burn out and die.”

“Sov in!” from the op.17 set asks a sick child to rest (“…my little patient, just sleep!”) in heart-breaking fashion, and “En slända” bids a sweet farewell to a dragonfly. The texts may be downbeat, but the settings have the chilly radiance so typical of Sibelius. “Säv, säv, susa” is a bleak tale of a young girl’s drowning, but the music is exquisite. “Var det en dröm?” recalls a long-gone love affair, “a dream like a wildflower’s life/so brief in the verdant meadow.” Norwegian mezzo-soprano Marianne Beate Kielland’s characterful performances are matchless, each song’s distinct character apparent, and it’s nice to read her heartfelt thanks to her pronunciation coach, Barbro Marklund. Petre Popelka’s Norwegian Radio forces provide stylish support. Texts and translations are provided, and Lawo’s engineering is rich and detailed. One of my discs of the year.

Add comment