Schumann was the first major composer to pair solo piano with string quartet. His 1842 quintet remains one of the best examples of the genre, perched between chamber introspection and public assertiveness. It's full of splendid moments, springing into life with inexhaustible exuberance. Schumann's fiendish piano writing rarely lets up, and one of the joys of this beautifully nuanced performance from the San Francisco based Alexander Quartet is the contribution made by pianist Joyce Yang. She's beautifully integrated into the sound picture, understading that this isn't a concerto in disguise. There's a delicious moment when the first movement's second theme is recalled by cello and viola, Yang's soft, syncopated chords providing flawless support. The movement's close is sensational. I liked the Alexanders' understated treatment of the In modo d'una Marcia, and the Scherzo and Allegro ma non troppo are glorious. The ineffable momentum never falters, especially in the latter's coda, where the first movement's theme makes a surprise return.

Coupling it with Brahms's Quintet makes musical and historical sense. Originally conceived in 1862 as a string quintet, and subsequently recast by Brahms as a work for two pianos, it became a piano quintet in 1864 on the advice of Clara Schumann. The work's darker, weightier cast is nicely caught, and Yang's rhythmic drive propels the music along – the work lasts 41 minutes but feels more compact. The Finale's brilliant contrapuntal writing possesses plenty of clarity, but it's Brahms's expansive opening movement which really grips. Every note counts; it's difficult to imagine this work scored for a different combination of instruments. Classy playing and vivid recording make this a highly desirable CD.

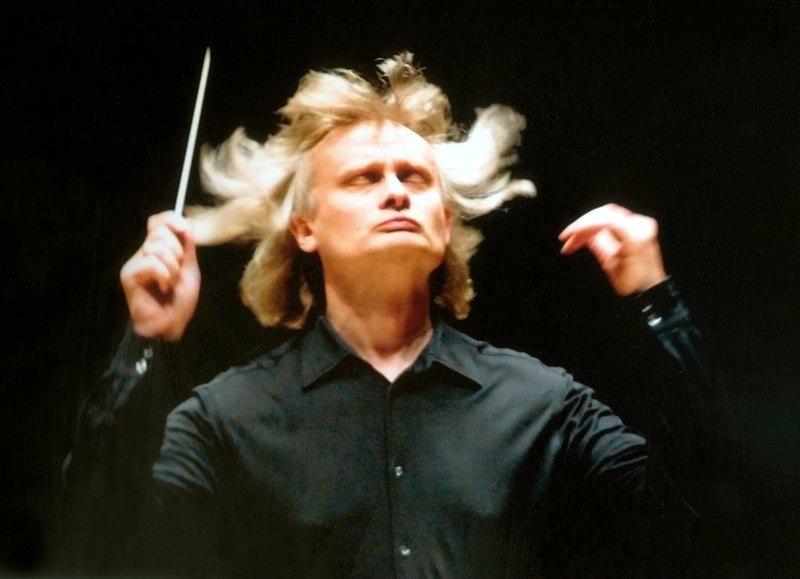

The Polish composer and conductor Paul Kletzki's flourishing career in 1920s Germany came to an abrupt halt in the 1930s. He moved initially to Italy, fleeing to Switzerland in 1941. Before leaving, he packed his manuscripts into a chest which was left in the basement of a Milan hotel. Which was subsequently bombed. Kletzki also assumed that his German publishers had destroyed his scores. He became a well-known conductor in the post-war era, fondly remembered for his work with the Philharmonia in the 1950s. Excavations in Milan in 1965 uncovered the chest containing Kletzki's scores – he, sadly, was afraid to open it, fearing that that the contents would have turned to dust. Kletzki's widow Yvonne had a peek after her husband's death in 1973, and found the scores to be perfectly preserved. One of them, the 1928 Violin Concerto, receives its first recording here. It's a ripe, confident piece; Kletzki's luminous, extravagant scoring and his flexible use of tonality give the work a unique and highly individual flavour. It receives a fantastic performance here; Robert Davidovici's full-blooded tone is just what the work deserves, and Grzegorz Nowak's Royal Philharmonic are fearlessly accurate – listen to those the upper strings at the start of the Allegro giocoso.

The couplings are generous. The opening of Szymanowski's Violin Concerto no 2 sounds as hazy and languid as it's ever been, the orchestral piano nicely audible, but there's plenty of energy in reserve; the concerto's deliriously upbeat final bars really hit home. Davidovici and Nowak close the disc with an unusually entertaining, neo-romantic take on Lutosławski's late Partita. The quieter moments swoon, aided by Roderick Elms's marvellous piano obbligato. Lutoslawski's bustling Presto coda provides an emphatic close to a well-planned release. Brilliant sound too, from the orchestra's Cadogan Hall.

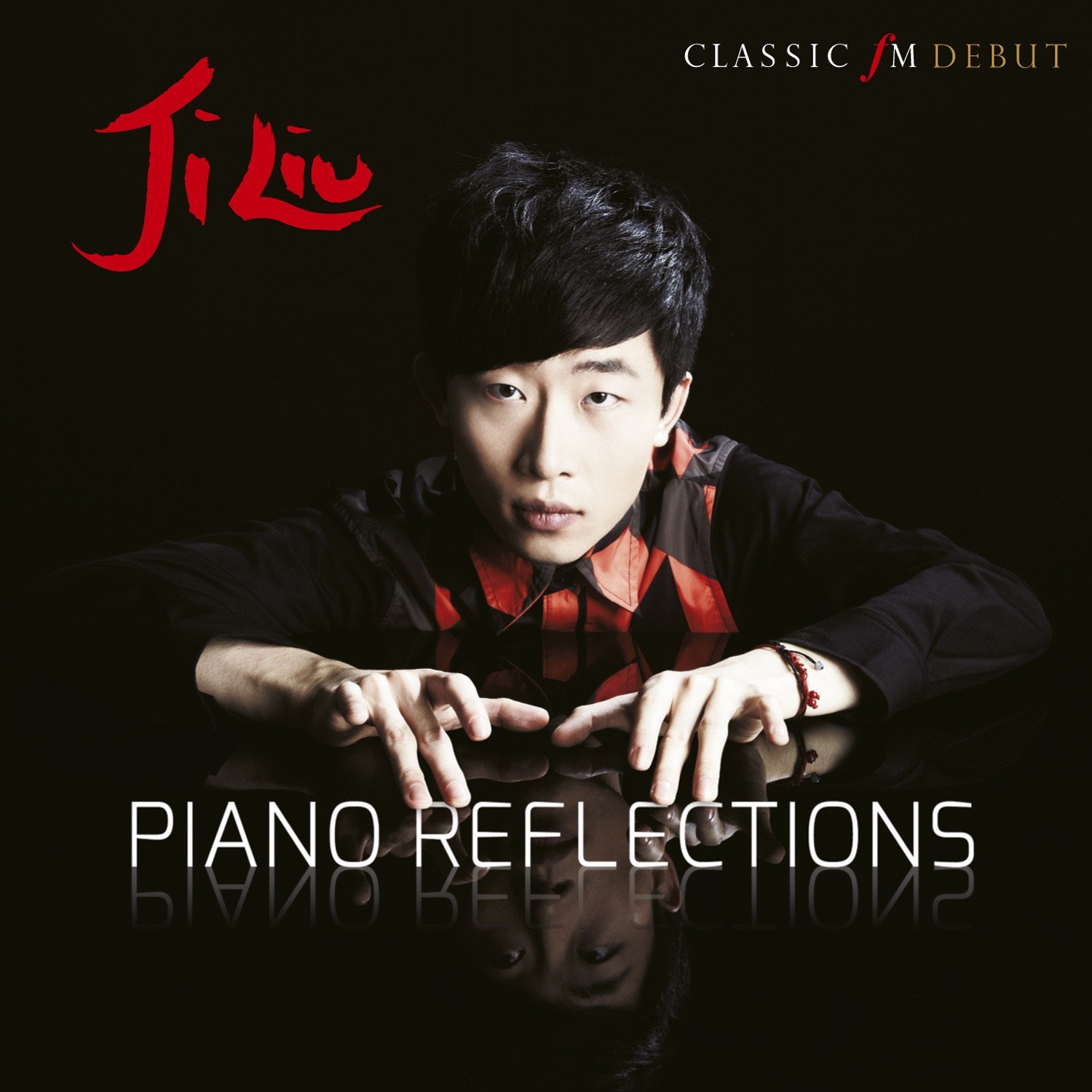

It's tempting to be sniffy about a CD like this before you've removed the shrinkwrap. Young Chinese pianist Ji Liu's debut album has been riding high in the UK classical top 20 for weeks. It's heavily promoted by Classic FM. Search for information about Liu's choice of repertoire in the CD booklet and you'll find naff-all, but we do get some suitably moody photos as compensation. The album deservedly credits producer Andrew Cornall and engineer Philip Siney, but gives equal billing to the team responsible for Liu's outfits, hair and make up. Ignore one's inner snob, and there's loads to admire and enjoy here – and what's wrong with anyone trying to popularise classical piano music, as long as they've got the technique and the soul? Liu bravely attempts to have it both ways, including some weighty music alongside the fluff. Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata is rather nicely done, particularly a flowing Adagio sostenuto and a hair-raising Presto agitato. Debussy's Suite Bergamasque has plenty of wit, and Liu's left hand work in the Passepied is dazzlingly in its clarity. Schubert's Ständchen, transcribed by Liszt and Horowitz, has the requisite lilt. Liszt's Liebestraum no 3 is played straight, and avoids cheesiness. A pair of Chopin nocturnes don't quite plumb the depths though; there's the niggling sense that Liu is skating over the surface emotionally.

Rachmaninov's transcription of the Scherzo from Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream is fleet and fun. Saint-Saëns's Danse Macabre is technically brilliant, though Liu's noisy bravura comes close to sounding oppressive at several moments. An enjoyable if overblown arrangement of Lü Wencheng's Autumn Moon over the Calm Lake offers welcome respite.

Add comment