Henrique Oswald: Piano Concerto, Saint-Saëns: Piano Concerto No. 5 Clélia Iruzun (piano), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Jac van Steen (Somm)

Henrique Oswald: Piano Concerto, Saint-Saëns: Piano Concerto No. 5 Clélia Iruzun (piano), Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Jac van Steen (Somm)

You can never have enough of Saint-Saëns’ Piano Concerto No. 5, a piece tailor-made to soothe and delight during stressful times. It gets better and better with repeated listenings. Where to start? With the opening bars – a few seconds of perfumed incense, before the piano’s innocent, unadorned entry. We’re a long way from the Brahms D minor. Clélia Iruzun gets the work’s playfulness and charm, knowing exactly when to inject some adrenalin or pull things back. Sample her tenderness in the first movement’s tender second subject, or her pulling the stops out in the development. Saint-Saëns’ slow movement is a treat here, Iruzun’s opening flourish ear-catching, her impersonations of frogs, crickets and Javanese gamelan wholly convincing. Ships’ propellers rumble away in the motoric last movement, one of the most joyous concerto finales out there. It’s a genuinely marvellous piece. We’re not short of good recordings, but this one is excellent, and Jac van Steen’s Royal Philharmonic provide extrovert support.

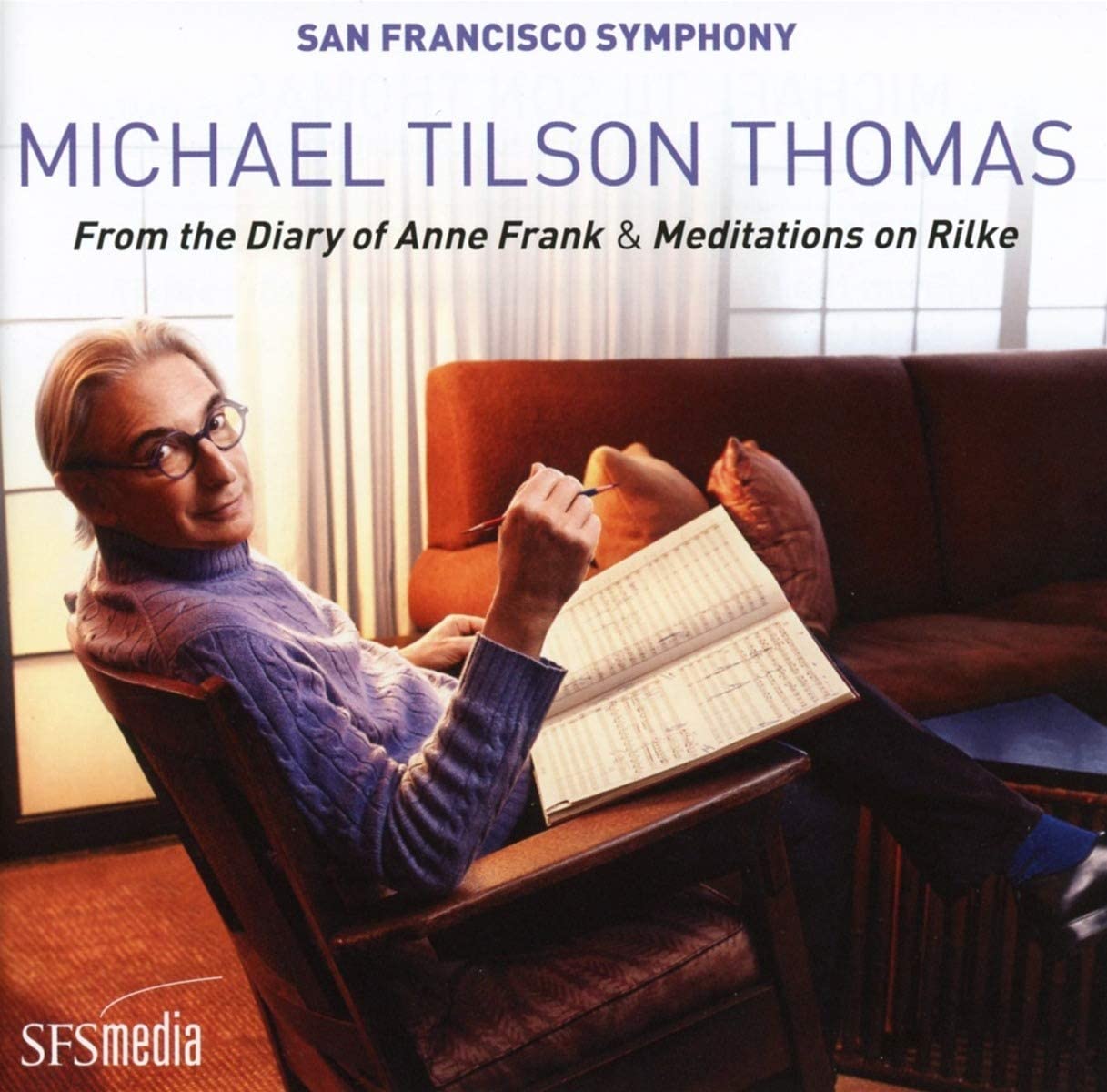

It’s coupled with two rarities. Henrique Oswald was born in Rio de Janeiro in 1852, travelling to France as a teenager to continue his musical studies. He became a friend of Saint-Saëns in the late 1880s and enjoyed a similarly long and productive career. Oswald’s Piano Concerto takes a while to start warm up, its long first movement heavily indebted to European models. The Adagio is far more individual, and there’s a quirky virtuoso finale, Iruzun letting rip. She also throws in another Brazilian novelty, Alberto Nepomuceno’s little Suite Antigua. Modelled on Grieg’s Holberg Suite, and written while the composer and his Norwegian wife (the splendidly named Walborg Rendtler Bang) stayed with Grieg in 1893, it’s modest, undemanding fun. The closing “Rigaudon” is catchy, but I keep returning to the little third movement “Air”. An enjoyable anthology. Michael Tilson Thomas: From the Diary of Anne Frank, Meditations on Rilke Isabel Leonard (narrator), Sasha Cooke (mezzo-soprano), Ryan McKinny (bass-baritone), San Francisco Symphony/Michael Tilson Thomas (SFS Media)

Michael Tilson Thomas: From the Diary of Anne Frank, Meditations on Rilke Isabel Leonard (narrator), Sasha Cooke (mezzo-soprano), Ryan McKinny (bass-baritone), San Francisco Symphony/Michael Tilson Thomas (SFS Media)

Michael Tilson Thomas’s Meditations on Rilke draws you in within seconds, its saloon bar piano noodlings seamlessly melding into a Mahler quote. The transparent scoring also echoes Mahler’s own, Tilson Thomas setting six Rainer Maria Rilke poems for male and female voices. There’s an overt nod to Das Lied von der Erde, the verses here describing simple earthly pleasures and the joy and sadness felt as autumn passes. “Whoever is alone now will remain alone,” sings bass-baritone Ryan McKinny in the first song. Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke is superb in the short second number, an appealing blend of European art song and 20th century Americana. The fifth, “Imaginary Biography” is a propulsive duet, and “Autumn” provides a bittersweet coda. By which time you’re aware of Tilson Thomas’s huge debt to his mentor Leonard Bernstein, the highbrow and lowbrow elements brilliantly mingled.

It’s coupled with From the Diary of Anne Frank, first performed in 1990 with Audrey Hepburn as speaker. Tilson Thomas acknowledges that the work was inspired as much by its original narrator as by Anne Frank, Hepburn’s role taken on by mezzo Isabel Leonard in this 2018 live performance. Frank’s bleak but gripping diary extracts rightly occupy the foreground, Tilson Thomas neatly reflecting their progression from naïve optimism to tragedy, Frank’s final utterance of “…in spite of everything, I still believe people are really good at heart”, accompanied by music implying that there’s still some hope. Performances of both works are as authoritative as you’d expect, and SFS media provide full texts and translations.

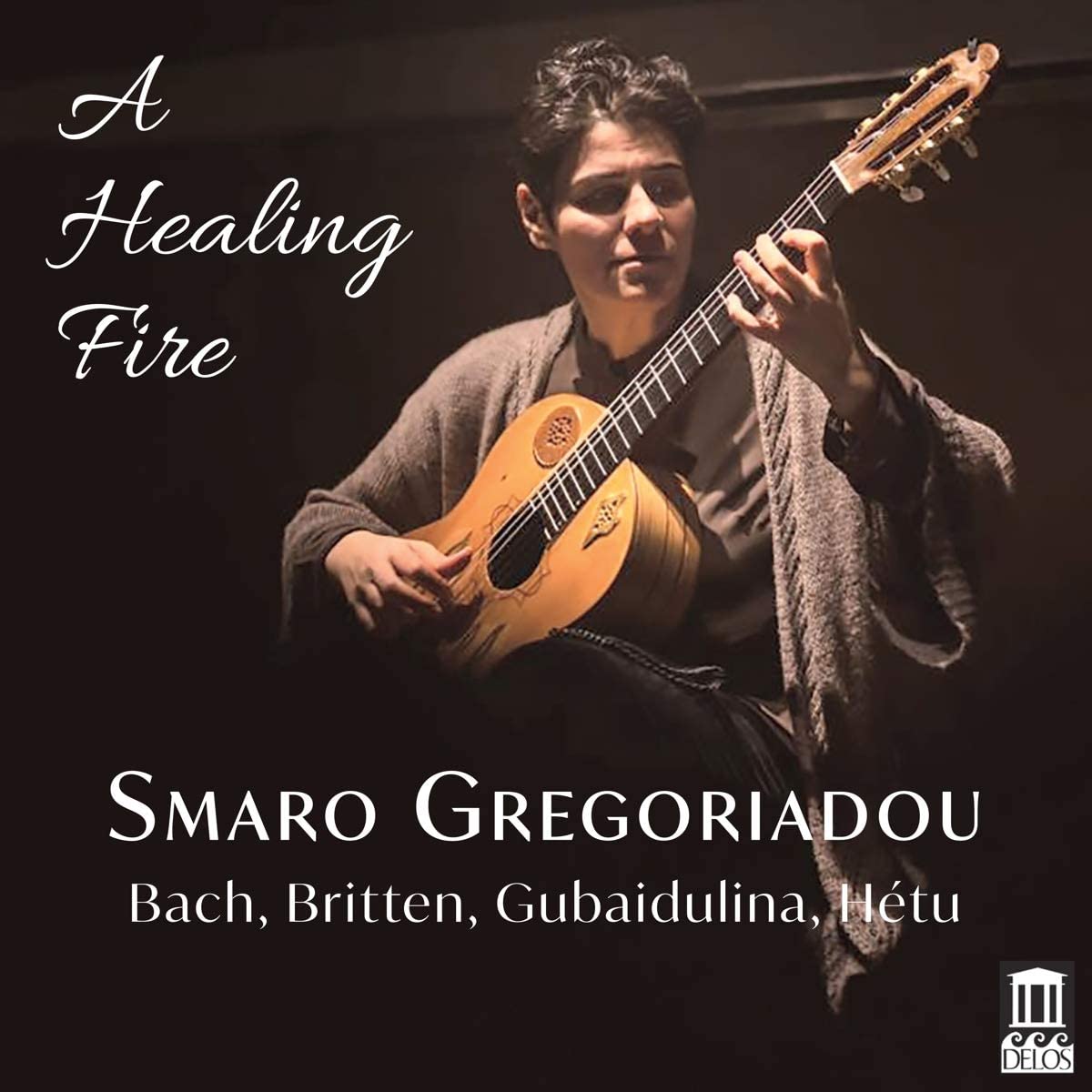

A Healing Fire – music by Bach, Britten, Gubaidulina and Jacques Hétu Smaro Gregoriadou (guitar) (Delos)

A Healing Fire – music by Bach, Britten, Gubaidulina and Jacques Hétu Smaro Gregoriadou (guitar) (Delos)

One interesting aspect of Greek guitarist Smaro Greoriadou’s playing is her willingness to experiment technically, the tunings and instruments chosen to suit the musical requirements of each work. So, her transcription of Bach’s Violin Sonata No. 2 follows the composer’s own keyboard version in switching from A minor to D minor, Gregoriadou using a guitar tuned a major third higher than usual. Her choice pays off, the instrument’s leaner, crisper timbre closer to that of the harpsichord. There’s an intensity and tautness to the sound which heightens the music’s expressivity. Every flourish in Bach’s opening “Grave” tells, followed by a cogent, elegant fugue. And I like the steely power of the final movement, music described by Gregoriadou as “smooth but assertive”. For the rest of the disc we slip back down to conventional tuning, both instruments fitted with pedal mechanisms allowing the sound to be modified by the player. The one familiar work is Britten’s Nocturnal after John Dowland, a sequence of variations based on Dowland’s “Come, heavy sleep”, the theme only appearing at the very end. This is thorny, late Britten, the spare textures easily offset by the warmth of Gregoriadou’s playing, the arrival of the Dowland melody an effective coup de théâtre.

Sofia Gubaidulina’s Serenade dates from 1960, three minutes of arresting but pained musing, ending suddenly and serenely with a G major chord. Rarer still is the Op. 41 Suite by French-Canadian composer Jacques Hétu. He described himself in 1996 as “a rather solitary hiker”, a follower of Dutilleux rather than Boulez. This five-movement work is an accessible treat, Hétu’s language alluding to conventional tonality while remaining distinct and fresh. As with Hindemith, thickets of thorny dissonance have a habit of resolving, magically, onto consonant chords. An enjoyable anthology, beautifully played and handsomely recorded, Gregoriadou’s stated objective to “offer encouragement and hope against today’s dystopia and chaos” accomplished with ease.

Add comment