Extract: Tim Lawrence's Hold On To Your Dreams | reviews, news & interviews

Extract: Tim Lawrence's Hold On To Your Dreams

Extract: Tim Lawrence's Hold On To Your Dreams

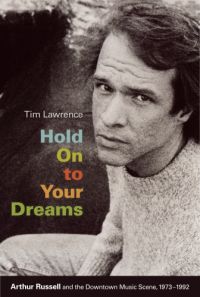

A chapter from the biography of Arthur Russell, New York downtown music guru extraordinaire

Linked to Joe Muggs' interview with Tim Lawrence on theartsdesk, this is extracted from the introduction of Hold On To Your Dreams: Arthur Russell and the Downtown Music Scene, 1973-1992.

Arthur Russell hailed from the Midwest, yet felt at home in downtown New York. Outwardly normal to those who observed his checkered shirt and acne-scarred face, he trod the maze-like streets that ran from the battered tenements of the East Village to the abandoned piers on the West Side Highway for hours at a time, and on a daily basis.

The labyrinthine infrastructure and contrasting neighborhoods of lower Manhattan suited his purpose: equipped with a portable tape recorder or, when it became available, a Sony Walkman, Russell would play Abba alongside Mongolian throat music, or Bohannon back-to-back with Terry Riley, or Peggy Seeger followed by Grandmaster Flash - selections that were drawn from the global spectrum of sound and summoned the disjunctive backdrop of the city. Stopping only to offer his headphones to a friend, or to note an idea on one of the score sheets he stuffed into his bulging pockets, or to watch the sunset over the Hudson, Russell was a musical nomad who had downtown imprinted onto his sneakers.

The labyrinthine infrastructure and contrasting neighborhoods of lower Manhattan suited his purpose: equipped with a portable tape recorder or, when it became available, a Sony Walkman, Russell would play Abba alongside Mongolian throat music, or Bohannon back-to-back with Terry Riley, or Peggy Seeger followed by Grandmaster Flash - selections that were drawn from the global spectrum of sound and summoned the disjunctive backdrop of the city. Stopping only to offer his headphones to a friend, or to note an idea on one of the score sheets he stuffed into his bulging pockets, or to watch the sunset over the Hudson, Russell was a musical nomad who had downtown imprinted onto his sneakers.

New York, a hub for sonic invention, hosted a spell of particularly manic productivity during the 1970s and 1980s, and Russell, who lived in the city from 1973 to 1992, became one of its most audacious musicians. Striving for a level of sonic mobility that matched his winding walks and unpredictable tape selections, Russell wrote and recorded folk, pop, new-wave, dance, and orchestral music while composing songs for the cello, all in a rush of scene-hopping simultaneity that carried him through many of downtown’s most vital spaces. Disco at the Loft, the Gallery, and the Paradise Garage; new music at the Kitchen Center for Video and Music (better known simply as “the Kitchen”) and the Experimental Intermedia Foundation; country at Sobossek’s and the Lower Manhattan Ocean Club; new wave and experimental pop at CBGB’s and Danceteria; hip-hop and electro at the Roxy; poetry at St Mark’s; salsa on the streets of the East Village - skipping between these sounds and scenes with the nonchalant ease of a kid playing hopscotch, Russell embodied the creative mayhem of an era in which parties shimmered with energy and gigs brimmed with intent. A roamer at heart, Russell’s performances and recordings made him uniquely qualified to navigate the baroque complexity of the downtown music scene during this period.

It would have been forgivable if Russell’s music sounded like the work of an amateur idealist, such was the scope of his migrant hike, but in fact his contributions were consistently notable. As an orchestral musician he worked as the music director at the Kitchen, the groundbreaking venue for experimental composition, and recorded pieces for the pioneering composer Philip Glass and the avant-garde theatre director Robert Wilson. In the pop/rock sphere Russell put together demos for Columbia Records’ legendary A&R executive, John Hammond, who believed Russell had the potential to become the next Bob Dylan, and he also played with the Necessaries, a new-wave band signed to Sire Records. Exploring the outer reaches of dance, he recorded a series of twelve-inch singles that blazed a trail between disco and house, working with pioneering engineers, producers, and remixers such as Bob Blank, Walter Gibbons, François Kevorkian, and Larry Levan. As he deepened his work, he cultivated a critically acclaimed voice-cello aesthetic that drew on orchestral music, dub, folk, and dance. Along the way he co-founded Sleeping Bag Records, one of the most influential independent labels for hip-hop and club music in the 1980s.

Russell recognized that the new-music compositional movement, minimalist rock, and disco/dance shared an interest in stripped-down instrumentation, trancelike repetition, and affective intensity, and so he worked between genres; while many of his contemporaries found his vision unconvincing, history has demonstrated he was simply ahead of his time. As a composer, Russell helped pioneer the eventually prolific dialogue between orchestral music and pop/rock, and he reached out to black dance with more energy than any of his downtown peers. His use of classical Indian, Western orchestral, and jazz techniques helped establish the future coordinates of mutant disco, or disco-not-disco. And although some deemed his introduction of a skittish syncopation into his twelve-inch repertoire to be undanceable, the sound went on to be popularized by brokenbeat and then dubstep years down the line. Anticipating the emergence of indie music, Russell also developed a strand of folk-oriented pop that was emotionally honest and delicately vulnerable. By the time indie had established this style as its own, he was busy introducing a black funk and hip-hop sensibility into his electronic pop - a combination that remains a leap too far for most guitar bands to this day.

Russell recognized that the new-music compositional movement, minimalist rock, and disco/dance shared an interest in stripped-down instrumentation, trancelike repetition, and affective intensity, and so he worked between genres; while many of his contemporaries found his vision unconvincing, history has demonstrated he was simply ahead of his time. As a composer, Russell helped pioneer the eventually prolific dialogue between orchestral music and pop/rock, and he reached out to black dance with more energy than any of his downtown peers. His use of classical Indian, Western orchestral, and jazz techniques helped establish the future coordinates of mutant disco, or disco-not-disco. And although some deemed his introduction of a skittish syncopation into his twelve-inch repertoire to be undanceable, the sound went on to be popularized by brokenbeat and then dubstep years down the line. Anticipating the emergence of indie music, Russell also developed a strand of folk-oriented pop that was emotionally honest and delicately vulnerable. By the time indie had established this style as its own, he was busy introducing a black funk and hip-hop sensibility into his electronic pop - a combination that remains a leap too far for most guitar bands to this day.

Despite his itinerant sensibility, Russell has been recognized largely for just one set of recordings, his dance productions, which charted an aesthetic escape from the commercial cul-de-sac of late disco. Featuring David Byrne’s highly-strung rhythm guitar, the twelve-inch single “Kiss Me Again” contained enough dissonance for it to become Sire’s first foray into the disco arena. Remixed by Larry Levan, “Is It All Over My Face?” supplanted the polished aesthetic of late seventies disco with the bumpier atmosphere of the downtown dance floor. The equally pivotal “Go Bang! #5” featured a combination of orchestral and R&B musicians as well as the studio trickery of François Kevorkian. Even “Let’s Go Swimming” and “School Bell/T reehouse,” which failed to impress DJs when they were released, have resonated with gathering force over time. Russell’s twelve-inch dance singles outsold his nondance releases by some distance, and this trend continued for several years after he died, during which time they appeared with gathering frequency on compilations that explored the less commercial recordings of the disco era as well as its mutant aftermath. Yet they also reverberated beyond dance, for Russell was set on taking the marginalized aesthetics of disco and even hip-hop into the heart of down-town.

Quirky, fragile, and pensive, Russell’s songs didn’t have anything like the same kind of impact as his dance productions, in part because so few of them were released, but a series of posthumous albums have highlighted this side of his craft. “I don’t think there’s any other songwriting where the music and the lyrics are of the same order, ” says the bass player and song-writer Ernie Brooks, who worked with Russell across the better part of two decades. “Musically Bob Dylan was not nearly as advanced as Arthur. John Lennon comes close. There are songs and there are songs, but Arthur’s songs are the ones I always want to listen to. ” Unsure of his looks as well as his voice, Russell was always on the lookout for a vocalist who could deliver his compositions to a wider audience, yet most of the candidates ended up deferring back to Russell, whose agile technique enabled him to sail across his hieroglyphic lines. Invention came easily to him, and in May 2004 the Wire included Russell among its list of sixty writers who have contributed to the reinvention of the song form.

Quirky, fragile, and pensive, Russell’s songs didn’t have anything like the same kind of impact as his dance productions, in part because so few of them were released, but a series of posthumous albums have highlighted this side of his craft. “I don’t think there’s any other songwriting where the music and the lyrics are of the same order, ” says the bass player and song-writer Ernie Brooks, who worked with Russell across the better part of two decades. “Musically Bob Dylan was not nearly as advanced as Arthur. John Lennon comes close. There are songs and there are songs, but Arthur’s songs are the ones I always want to listen to. ” Unsure of his looks as well as his voice, Russell was always on the lookout for a vocalist who could deliver his compositions to a wider audience, yet most of the candidates ended up deferring back to Russell, whose agile technique enabled him to sail across his hieroglyphic lines. Invention came easily to him, and in May 2004 the Wire included Russell among its list of sixty writers who have contributed to the reinvention of the song form.

The ability to move without inhibition - to record and listen without prejudice - was pivotal to Russell. When asked how his voice-cello album World of Echo (1986) related to earlier dance releases, he replied, “I think, ultimately, you’ll be able to make dance records without using any drums at all,” forgetting to mention that choreographers were already working with his acoustic songs. As if to demonstrate the mutability of sound, Russell enjoyed rolling the same set of lyrics over a range of instrumental back-drops, and he ended up moving with such freedom it became impossible to associate him with a single style. This set him apart from other radically open-minded downtowners, such as Rhys Chatham, Philip Glass, Peter Gordon, and Peter Zummo, who worked across art music, pop, rock, and jazz, yet were ultimately rooted in the compositional scene, as well as from Laurie Anderson and David Byrne, whose eclecticism could be located in experimental pop. No navigation system could pinpoint the whereabouts of Russell. “He was way ahead of other people in understanding that the walls between concert music and popular music and avant-garde music were illusory, that they need not exist, ” comments Glass, who participated in the exploration of rock while remaining rooted in orchestral music. “He lived in a world in which those walls weren’t there.”

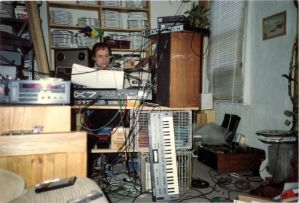

It’s tempting to believe that each time Russell picked up a musical instrument or entered a recording studio, he paused to wonder what would happen if he tried to do things differently. Russell devolved the responsibilities of the conductor to his musicians during rehearsals for an orchestral performance; he shepherded a bunch of percussion-happy dancers into Blank Tapes Studios in order to capture their energy on vinyl; he opened windows to let the “musicianship of the street” feed into his mixes; he encouraged gospel-trained vocalists to unlearn what they had been taught in order to become more expressive; and when he spotted an old school friend playing a broken guitar, he whisked him into the studio because, as Donald Murk (a companion from that moment) notes, he believed that “everybody has a voice.” As Russell explored the limits of musicianship, accomplished collaborators gleaned ideas about how they could develop their practice. “Arthur played a ‘classical/acoustic’ instrument, yet embraced and experimented with every new electronic gadget he could afford or get his hands on,” explains the percussionist Mustafa Ahmed. “Whenever he learned about a new drum machine or synthesizer, he would tell me about it. In spite of my initial opposition, he purchased electronic drum pads and gave them to me to use when I performed with him. That forced me to learn the new technology, and I eventually came to incorporate these new devices into other aspects of my music.”

In the end Russell spread himself across too many scenes and worked with too many musicians to build up a major reputation in a single genre, yet his lack of commercial success cannot be attributed solely to the music industry’s distrust of eclecticism. Russell’s perfectionism was peppered with obstinacy – on one occasion he spent a whole day fine-tuning the sound of a kick drum while his co-musicians waited to begin - and collaborators became so accustomed to his protracted methods they learned to stop asking what they were working on, or when a certain piece might be finished. The Walkman contributed to Russell’s indecisiveness inasmuch as it enabled him to switch between two versions of a demo recording again and again as he tried to decide which was superior. But although Russell found it easy to become embroiled in a cycle of introspection, his recordings rarely suffered from the attention to detail. Like that of an accomplished improviser, the ease of his sound masked the prodigious amount of work that went into its making.

There was something beautiful about Russell’s reluctance to decide on a final mix for many of his works. Playing, recording, and mixing amounted to a process of possibility, with every route a choice almost too tempting to resist, and the step of deciding on a final version - when a song would become static and therefore experience a form of death - often too painful to take. Instead Russell preferred to see music as a process that could re- produce itself in infinite ways and, in so doing, hint at the complexity and innate possibility of the universe. When he wrote orchestral music, Russell was drawn to the “generative” or “open form” approach championed by Christian Wolff (one of his mentors) because it allowed the musicians to embark on an uncharted exploration of sound. Dance music appealed in part because the practice of remixing allowed songs to experience several lives. Opportunities to release multiple versions of the same song were otherwise scarce, yet Russell generated something like a thousand reel-to-reel tapes of unreleased recordings. Because much of that music was unfinished, it contained the promise of future life.

Nevertheless Russell’s perfectionism and philosophical resistance to finishing shouldn’t obscure the fact that his output was substantial before he died in 1992 of complications arising from AIDS. In addition to his twelve-inch singles, Russell released four albums of his own music and two albums with the Necessaries, even though he didn’t release any of the music recorded during the last five years of his life - a period of deliberate procrastination that risks overshadowing the years in which he was notably more successful (in terms of delivering an end product). “In those days it was hard to get a record released, and Arthur released more records than any of us,” notes Ned Sublette, a downtown collaborator. “That was part of his mystique. Despite everything, he was visibly in the process of creating a body of work on record. ” Russell also laid down enough electronic pop, folk-oriented rock, acoustic songs, and off-the-wall dance tracks to fill four posthumous albums of previously unreleased material - Another Thought (1994), Calling out of Context (2004), Springfield (2006), and Love Is Overtaking Me (2008) – while another posthumous release, First Thought Best Thought (2006), included previously unreleased compositional pieces.

Nevertheless Russell’s perfectionism and philosophical resistance to finishing shouldn’t obscure the fact that his output was substantial before he died in 1992 of complications arising from AIDS. In addition to his twelve-inch singles, Russell released four albums of his own music and two albums with the Necessaries, even though he didn’t release any of the music recorded during the last five years of his life - a period of deliberate procrastination that risks overshadowing the years in which he was notably more successful (in terms of delivering an end product). “In those days it was hard to get a record released, and Arthur released more records than any of us,” notes Ned Sublette, a downtown collaborator. “That was part of his mystique. Despite everything, he was visibly in the process of creating a body of work on record. ” Russell also laid down enough electronic pop, folk-oriented rock, acoustic songs, and off-the-wall dance tracks to fill four posthumous albums of previously unreleased material - Another Thought (1994), Calling out of Context (2004), Springfield (2006), and Love Is Overtaking Me (2008) – while another posthumous release, First Thought Best Thought (2006), included previously unreleased compositional pieces.

With more albums of fresh material promised, Russell is beginning to look prolific, especially for a so-called serial procrastinator. Whether they nestled within or between the coordinates of genre, these recordings always sounded particular. “Russell’s work is stranded between lands real and imagined: the street and the cornfield; the soft bohemian New York and the hard Studio 54 New York; the cheery bold strokes of pop and the liberating possibilities of abstract art, ” wrote Sasha Frere-Jones in the New Yorker in 2004. “Arthur Russell didn’t dissolve these borders so much as wander past them, humming his own song.” Innocent yet sophisticated, light yet serious, smooth yet angular, Russell’s sonic identity contained seemingly irreconcilable contradictions, something that the Loft host David Mancuso captures when he describes him as being “Dylan and Coltrane rolled into one.” The guitarist Gary Lucas, who has worked with the “trailblazers” Captain Beeheart and Jeff Buckley, remains captivated by Russell, with whom he worked in the 1980s. “There was the Corn-Belt-transplanted-to-New-York sensibility, the gay sensibility, the Buddhist sensibility - everything was in the mix,” he comments. “That’s what the best artists do. They give you a striking sense of personality.”

Given his dynamic musical personality, it is perhaps surprising that Russell was also a bashful, complicated musician whose career could double as a tutorial in the frustration of narrative - including the tropes of self-made success and self-inflicted tragedy that run through so many biographies of musicians. Subdividing into a series of unresolved tangents, Russell’s life and work lacked a defining arc, and because his overwhelming concern was to get the music right, moments of commercial promise ended in argument or anticlimax. In the end Russell died a marginal figure because he wasn’t sufficiently self-centered, competitive, or coherent to convince the marketing departments of New York’s record companies to embrace his vision. But for those who judged him according to his ability to work collectively, creatively, and with contradiction, all without recourse to materialism and celebrity, his subjugated story suggested an alternative way of working in the world. “This was a musical revolt... and Arthur was part of it, ” Glass noted in a 1995 interview. “We all became accepted except Arthur... He was an underground musician to the end of his life.”

Russell remains a relatively marginal figure, even in accounts of the downtown era. Tom Johnson’s eyewitness account of downtown’s orchestral scene in the 1970s and early 1980s, The Voice of New Music, overlooks Russell, perhaps because the author (in the words of Sublette) “didn’t have a clue what our generation was doing.” Michael Musto was much more open to the innovative possibilities of popular culture, but his book Downtown celebrates the brash, the fashionable, and the extrovert, and Russell, who scored poorly on all of those counts, doesn’t get a mention. Marvin Taylor’s impressive edited collection from 2006, The Downtown Book, emphasizes the primitive anger, anxious nihilism, and postmodern confusion that ran through lower Manhattan between 1975 and 1984, and once again Russell doesn’t quite fit, even though downtown is lauded for having become a home for outsiders. Bringing together the photographs of Paula Court with a series of short essays by downtown players, the Soul Jazz publication New York Noise: Art and Music from the New York Underground, 1978–88 seemed certain to correct the historical record, but Russell was notoriously camera-shy and somehow slips away. A self-declared admirer, Simon Reynolds mentions Russell only briefly in his groundbreaking history of postpunk, Rip It Up and Start Again, because Russell didn’t have a significant impact on postpunk consciousness. Nor did Russell feature in Kyle Gann’s collection of writings on the downtown experimental scene, Music Downtown, perhaps because, as Gann wrote in his obituary of Russell, “he simply vanished into his own music.”

The omission of Russell doesn’t amount to a conspiracy, or even an act of negligence, because he didn’t insist upon being heard or seen. “His importance has not been appreciated as broadly as it should because he left such a small paper trail, ” comments Bernard Gendron, author of Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club, who didn’t include Russell alongside Laurie Anderson, Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham, and Peter Gordon in his list of the key representatives of downtown’ s “borderline aesthetic” because Russell left so little evidence of his work. As with many other histories of U.S. popular music, however, the foregrounding of downtown’s more audible and visible performers has resulted in the masculine and the straight being privileged above the feminine and the queer, as well as the white above the black and the Latin. While there is no disputing the influence of individuals such as Glenn Branca, James Chance, Rhys Chatham, and Richard Hell, as well as groups such as Blondie, the New York Dolls, the Ramones, Sonic Youth, Suicide, the Swans, Talking Heads, and the Velvet Underground, the historical focus on rock and its exchange with the noisier end of compositional music has helped strengthen the reputations of players who were already prominent. Insofar as they are recognized, African Americans have managed to appear on the periphery when they are masculine (such as the breakdancers and DJs of hip-hop, and the intrepid performers of free jazz) or when they have augmented white players (such as the session musicians who performed on [Talking Heads'] Remain in Light). Meanwhile women have appeared, in general, if they reproduced the masculine (e.g., Lydia Lunch, Patti Smith), embraced a boyish techno-coldness (e.g., Laurie Anderson), or played the blonde seductress (e.g., Debbie Harry). Even given these restraints, down-town’ s producers of pop, folk, and - above all – disco haven’t featured at all.

The omission of Russell doesn’t amount to a conspiracy, or even an act of negligence, because he didn’t insist upon being heard or seen. “His importance has not been appreciated as broadly as it should because he left such a small paper trail, ” comments Bernard Gendron, author of Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club, who didn’t include Russell alongside Laurie Anderson, Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham, and Peter Gordon in his list of the key representatives of downtown’ s “borderline aesthetic” because Russell left so little evidence of his work. As with many other histories of U.S. popular music, however, the foregrounding of downtown’s more audible and visible performers has resulted in the masculine and the straight being privileged above the feminine and the queer, as well as the white above the black and the Latin. While there is no disputing the influence of individuals such as Glenn Branca, James Chance, Rhys Chatham, and Richard Hell, as well as groups such as Blondie, the New York Dolls, the Ramones, Sonic Youth, Suicide, the Swans, Talking Heads, and the Velvet Underground, the historical focus on rock and its exchange with the noisier end of compositional music has helped strengthen the reputations of players who were already prominent. Insofar as they are recognized, African Americans have managed to appear on the periphery when they are masculine (such as the breakdancers and DJs of hip-hop, and the intrepid performers of free jazz) or when they have augmented white players (such as the session musicians who performed on [Talking Heads'] Remain in Light). Meanwhile women have appeared, in general, if they reproduced the masculine (e.g., Lydia Lunch, Patti Smith), embraced a boyish techno-coldness (e.g., Laurie Anderson), or played the blonde seductress (e.g., Debbie Harry). Even given these restraints, down-town’ s producers of pop, folk, and - above all – disco haven’t featured at all.

Russell’s story, which is also a story of his collaborations, counterbalances rather than displaces these versions of the downtown era. Russell lived in a neighborhood that was heavily Latin, went to clubs that were predominantly gay and black, hung out with women who were drawn to the ethereal, and wrote songs with guys who were interested in the sub lime. As he went about his work, Russell recorded rock and orchestral music, and when these scenes appeared to be trapped in a demographic or aesthetic loop, he mixed things up. “Arthur was always the one to bring in people from different backgrounds - blacks, gays, people from Brooklyn and the Bronx,” notes Zummo. “To him there was no question that these people could be drawn into the white downtown avant-garde scene. I would have never met Mustafa Ahmed if it hadn’t been for Arthur.” No other downtowner engaged with the visceral, creative, transcendental world of black gay aesthetics to the same degree as Russell, and the results could be heard in his performances and recordings. “Many New York artists around that time were using aggression and anxiety in their work,” wrote Ben Ratliff in the New York Times in 2004. “Russell’s work had no aggression in it whatsoever, but patience and kindness instead; this is one of the reasons it doesn’t now feel stuck in its time.”

If downtown was violent, poor, dangerous, competitive, and macho - and it’s worth questioning the extent to which the macho element might have overstated the toughness of the conditions—Russell tried to not let it get to him. He lived in the East Village because as well as being hazardous, it was rich in rhythm and community. He frequented the seedy dives where desolation and unease were de rigueur, but preferred to hang out in the celebratory venues of downtown dance. And while a number of downtowners expressed a combination of poetic aggression and anxious frustration, he chose to introduce fun, sensitivity, and humor into his music. Along with Tom Lee, his supportive partner, these factors might have helped Russell survive, for while most of his peers ended up leaving downtown for more moderate climes, he stuck it out until the end of his life. “Downtown was a discourse on the nullification of absolutes that needs the full cacophonous chorus to be heard,” comments the popular-culture critic Carlo McCormick in he Downtown Book. Because his inquisitive ear, light feet, and generous spirit led him to work in so many scenes, Russell offers a rather lovely way to explore the musical elements of this chorus.

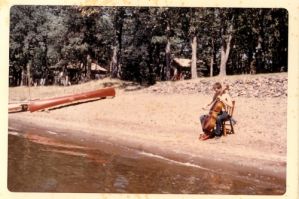

Photo credits: Arthur Russell playing the cello on a beach in Minnesota, circa September 1971. Photograph by Charles Arthur Russell, Sr. Courtesy of Charles Arthur Russell, Sr., and Emily Russell. / Arthur Russell in his home studio, 1990. Photograph by Tom Lee. Courtesy of Charles Arthur Russell, Sr., and Emily Russell. / Arthur Russell in a photo booth. Courtesy of Audika Records. / Arthur Russell in rural Iowa in the mid-1980s. Photograph by Charles Arthur Russell, Sr. Courtesy of Audika Records.

Buy Hold on To Your Dreams on Amazon

Add comment