Adaptability is the name of the game for big companies in the music business now. And Opera North’s streamed presentation of Beethoven's Fidelio from inside Leeds Town Hall is a prime example of just how adaptable things need to be.

The orchestra is down to 33: single (hardworking!) woodwind, two horns, two trumpets, no trombones, in a score reduction by Francis Griffin. The chorus numbers 24, and between them that’s going some for a socially distanced ensemble these days. The soloists are spread along the front of the extended platform, with space to act and interact to some degree. Lighting is limited but effective: on screen the orchestra remains almost hidden in the shadows, and there’s enough of a gap between Leonore (Rachel Nicholls, pictured below) and Jaquino (Oliver Johnston), Marzelline (Fflur Wyn) and Rocco (Brindley Sherratt) for it to seem almost credible that she should be taken for a boy and not a woman.

But that’s not all. Mark Wigglesworth conducts in a staging by Matthew Eberhardt that uses David Pountney’s adaptation of the libretto. Less is definitely more here: instead of spoken dialogue dominating much of Act One (and usually putting one in mind of “comic opera” of the Singspiel tradition), there is the neat, and much shorter, device of using Don Fernando (Matthew Stiff) as narrator, reading from his after-the-event report on what happened in the plot. This leaves the Beethoven music in its unalloyed glory and, though it may have been forced by circumstances, to my mind makes the show a much more satisfying one altogether.

But that’s not all. Mark Wigglesworth conducts in a staging by Matthew Eberhardt that uses David Pountney’s adaptation of the libretto. Less is definitely more here: instead of spoken dialogue dominating much of Act One (and usually putting one in mind of “comic opera” of the Singspiel tradition), there is the neat, and much shorter, device of using Don Fernando (Matthew Stiff) as narrator, reading from his after-the-event report on what happened in the plot. This leaves the Beethoven music in its unalloyed glory and, though it may have been forced by circumstances, to my mind makes the show a much more satisfying one altogether.

But haven’t we heard this somewhere before? For anyone present in the Bridgewater Hall, Manchester, back in February, yes. Then, beginning what was going to be a year of Beethoven celebrations, the Hallé gave a concert including Act Two of Fidelio under Sir Mark Elder, presented with the same Pountney narration device. And Elder’s Leonore and Rocco were the same singers, too. There’s a kind of symmetry, after all the lost opportunities of Covid year, in Opera North’s concluding 2020 with the same concept.

The filming presentation (Peter Maniura) is less ambitious than the recent streamed Hallé offerings, but does the job nonetheless (it’s just a pity the orchestra are so faintly lit, and the sound is, unsurprisingly, on the thin side at times). But the soloists do the very best they can as actors: Fflur Wyn, who was Marzelline also in the 2011 Opera North staged production, slots into her role with ease, and the great canon quartet, “Mir ist so wunderbar”, is cleverly presented as well as beautifully sung.

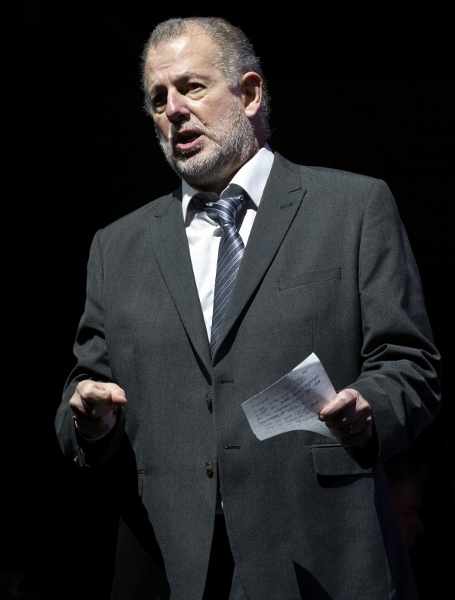

Though most of the soloists are dressed in anonymous matt black, Robert Hayward’s Pizarro (in another reference to the 2011 staging?) wears a lounge suit (pictured right) – anyone in one of those, these days, is clearly a slimeball. And Hayward is in fine, villainous, form, as exemplified in his “Ha, welch ein Augenblick”, with the chorus. He and Sherratt emote with vigour in “Jetzt, alter”. Rachel Nicholls comes gloriously into her own in “Abscheulicher! …” and “Komm, Hoffnung …” (some rewarding camera work here, and a thrilling emotional climax).

Though most of the soloists are dressed in anonymous matt black, Robert Hayward’s Pizarro (in another reference to the 2011 staging?) wears a lounge suit (pictured right) – anyone in one of those, these days, is clearly a slimeball. And Hayward is in fine, villainous, form, as exemplified in his “Ha, welch ein Augenblick”, with the chorus. He and Sherratt emote with vigour in “Jetzt, alter”. Rachel Nicholls comes gloriously into her own in “Abscheulicher! …” and “Komm, Hoffnung …” (some rewarding camera work here, and a thrilling emotional climax).

Toby Spence is an affecting Florestan: not quite in the Heldentenor mould, but singing with passion and cutting a noble figure. And he and Nicholls give a glorious “O namenlose Freude!”.

The chorus are magnificent: thank goodness they found space for them to sing in reasonable numbers, particularly in the Act One’s “O welche Lust” and a leaping, bounding “Heil sei dem Tag” and “Wer ein holdes Weib errungen”, as good finally triumphs. Under Wigglesworth’s direction, there is as much drama in the second act as anyone could ask for: the incisive sound of the reduced band makes an effectively Beethovenian impact here, and as we sweep into the finale, too, with Matthew Stiff finally revealing the rich quality of his singing voice.

Add comment