The music Britten composed in his twenties occupies a special place in his output. Even among his detractors there are some who begrudgingly concede that this early period is somehow different: fresher, more extroverted and daring, perhaps less driven by serving a purpose (or “being useful”, in the composer’s words).

As a Britten fan since my teens, I’ve always been captivated by the expressive depth, technical brilliance, and sheer beauty of practically all his music. His handling of the orchestra has, in particular, had a big influence on how I’ve approached my own works in this medium over the last decade or so. When, last year, Roger Wright at Britten Pears Arts commissioned an arrangement of Our Hunting Fathers, I was understandably delighted – though also slightly cautious: Britten’s technique was fully formed by the age of 20, and to reduce this shimmering, exquisite, and at times explosive orchestral score down to 12 instruments presented an entirely new challenge.

The work, a 30-minute “symphonic cycle for high voice and orchestra” with a text devised by WH Auden, was written in 1936 when the composer was 22 and counts among a handful of early masterpieces, including the Sinfonietta, Night Mail, and A Boy was Born, one the most sophisticated choral works in the repertoire. Though ostensibly a work about man’s relationship with animals – as pests, pets and prey – on a deeper level it is an uncompromising and impassioned expression of the pacifist principles Britten and Auden would maintain throughout their lives, written when fascism was erupting throughout Europe.

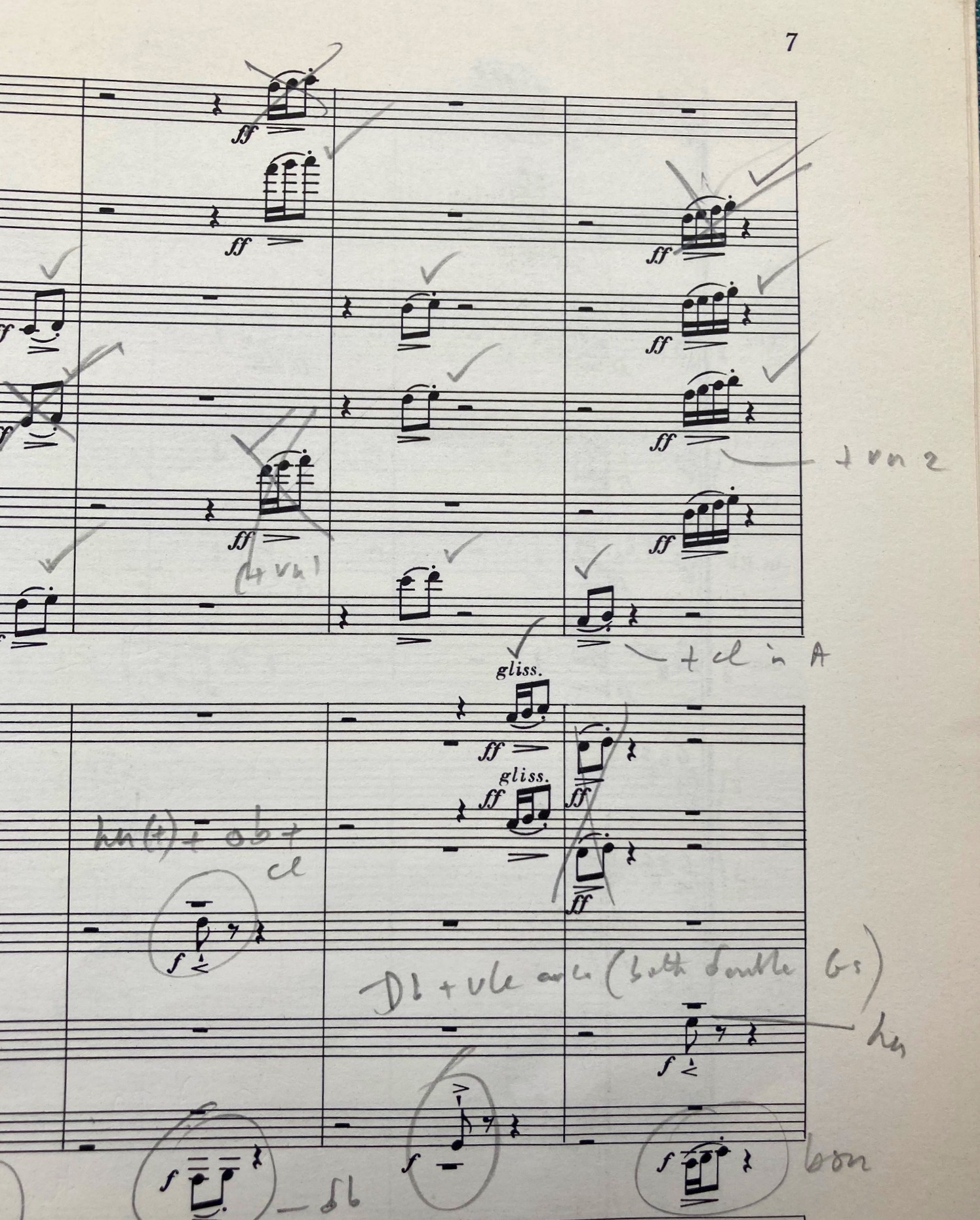

Britten’s score [a page of which pictured left with Phibbs' annotations] is full of unusual effects for the time, and it’s no wonder many in the audience – among them his publisher Ralph Hawkes and teacher Frank Bridge – were left baffled following its premiere at the Norwich and Norfolk Festival. In one of the most radical sections, “The Dance of Death”, a hair-raising display of virtuosity features whooping orchestral glissandos and trilling vocal effects, the solo soprano left stranded at the end to mutter “German” and “Jew” (names of dogs in a hunting pack) with chilling prescience. Later on, in the closing Funeral March, a disembodied, spectral xylophone, played in its lowest range, slowly marks time before being overwhelmed by an array of contorted wind lines, the result sounding a little like experimental jazz (it was this section that most worried Bridge).

Britten’s score [a page of which pictured left with Phibbs' annotations] is full of unusual effects for the time, and it’s no wonder many in the audience – among them his publisher Ralph Hawkes and teacher Frank Bridge – were left baffled following its premiere at the Norwich and Norfolk Festival. In one of the most radical sections, “The Dance of Death”, a hair-raising display of virtuosity features whooping orchestral glissandos and trilling vocal effects, the solo soprano left stranded at the end to mutter “German” and “Jew” (names of dogs in a hunting pack) with chilling prescience. Later on, in the closing Funeral March, a disembodied, spectral xylophone, played in its lowest range, slowly marks time before being overwhelmed by an array of contorted wind lines, the result sounding a little like experimental jazz (it was this section that most worried Bridge).

The work was duly savaged by many of the critics: “dire nonsense” (The Observer), “orchestral prank” (The Daily Telegraph), and “if it is a stage to be got through, we wish him safely and quickly through it” (The Times). It’s certainly a far cry from the world of Holst and Elgar, who had both died only two years earlier. If Britten is calling to account “Our Hunting Fathers” of pre-war Britain, he is perhaps also challenging his musical ones, whose (in his view) out-dated and at times amateurish methods he found exasperating, as chronicled in the daily diaries he kept up until the war.

There is indeed a certain rebelliousness and ferocity in this work, bolstered perhaps by Auden’s looming presence, which is unusual in Britten. As a student, his imagination had been ignited by European modernism, especially Schoenberg, Berg and Stravinsky, whose music he absorbed avidly at concerts and on the radio. Around 1930 he produced a clutch of pieces which are unrecognisable as Britten, fluent imitations in the mould of the trends that had so excited him – and while he quickly retreated, the influences were assimilated, if not harmonically then through an intricate method of manipulating and combining small melodic shapes, as well as adopting a more nuanced approach to orchestral writing. The often chamber-like intimacy and delicacy of his orchestration is also foreshadowed in Mahler, another of his – and Schoenberg’s – heroes. [Pictured below: The Hebrides Ensemble in rehearsal for the Snape Maltings performance of Our Hunting Fathers] What’s especially striking about Our Hunting Fathers is its fastidious approach to instrumental writing. Every phrase is packed with instructions: specific strings indications, fingering suggestions, and tiny dynamic nuances all compete for space on the page (he once remarked that he wished performers would simply “play what’s written”). One feels a certain frisson of excitement in the very process of scoring, as if Britten is unleashing his entire technical armoury, so assiduously assembled and polished over the previous decade, and setting it out for the world to see.

What’s especially striking about Our Hunting Fathers is its fastidious approach to instrumental writing. Every phrase is packed with instructions: specific strings indications, fingering suggestions, and tiny dynamic nuances all compete for space on the page (he once remarked that he wished performers would simply “play what’s written”). One feels a certain frisson of excitement in the very process of scoring, as if Britten is unleashing his entire technical armoury, so assiduously assembled and polished over the previous decade, and setting it out for the world to see.

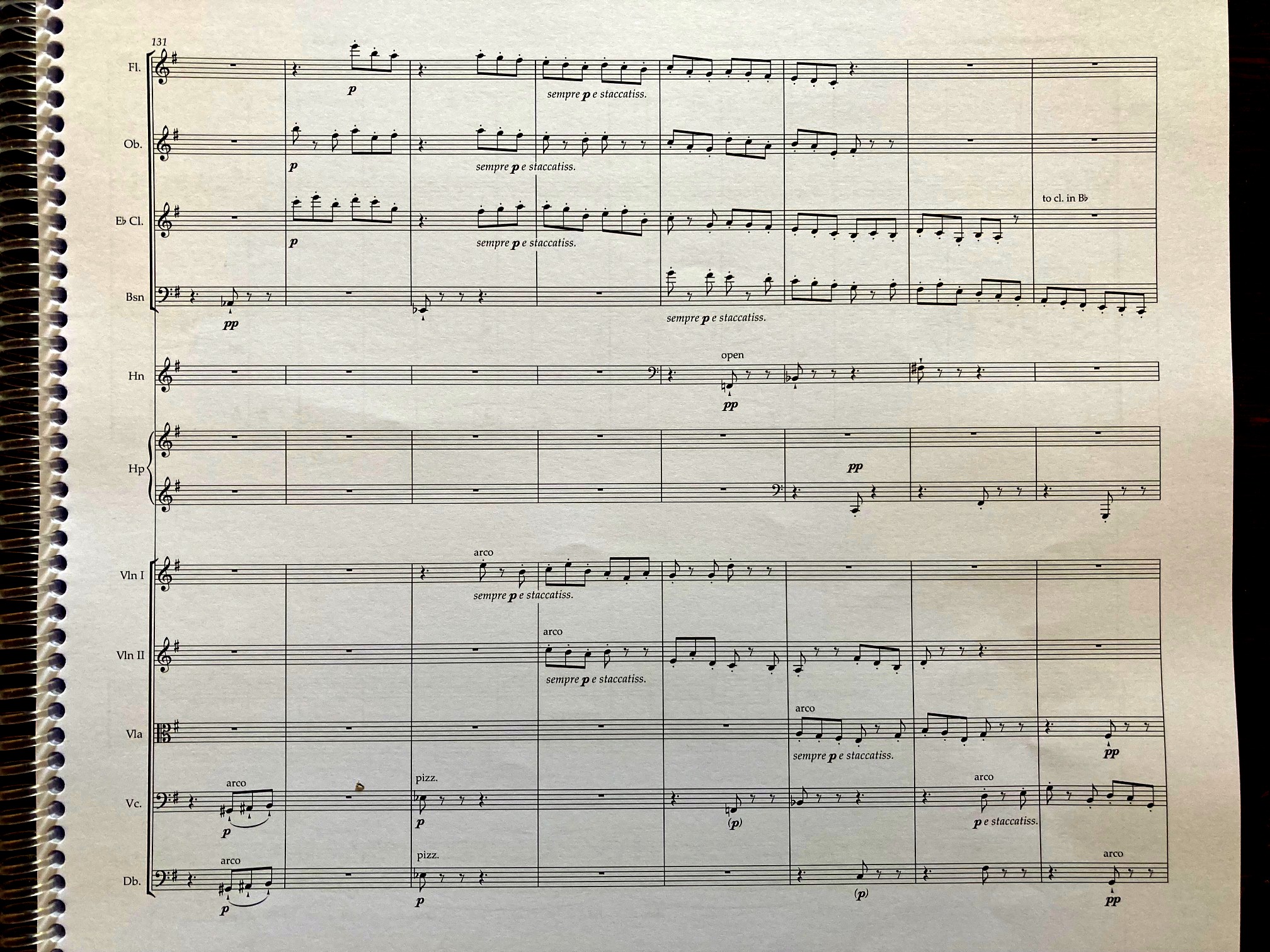

From the outset, I was determined not to regard the arrangement as a “compromise”, but rather as a version in its own right: a distillation, as best I could do, of the composer’s orchestral palette into a smaller instrumental form. My strategy was to keep the original scoring where possible, rather than impose my own style, and elsewhere to imagine what Britten might have done within the limitations of a chamber ensemble. Fortunately the music is fairly transparent, and rarely does a knotty web of counterpoint present serious problems, except (as mentioned earlier) in the closing pages, the toughest challenge of the arrangement. It often became a question of looking at which single instrument might best represent a combined sound (replacing, for example, two flutes and a clarinet with an oboe in my arrangement), and at other points substituting one instrument for another (a timpani with a double bass pizzicato, or a saxophone with a cor anglais). I spent several days rescoring a particularly complicated string passage, only to rip it up and start again, unconvinced that the delicacy of Britten’s original texture, which I’d tried to approximate, would work on a smaller scale.  Trying to get inside the mind of a 22-year old genius was a humbling – and occasionally humiliating – process [Pictured above: a page from Phibbs' rescored work]: Britten would peer nervously over my shoulder (“please don’t be too taxing on the poor horn player…” he might say), though I took some comfort from what I’d read about his pragmatic attitude to instrumental writing. Shortly after the war, Britten almost singlehandedly created the genre of chamber opera in order that new stage works, in a financially crippled England, could thrive and be toured around the country. Later, he would adapt works by Purcell and others to suit particular events at Aldeburgh, and was himself working within tight limitations for the GPO film unit at the very time of Our Hunting Fathers.

Trying to get inside the mind of a 22-year old genius was a humbling – and occasionally humiliating – process [Pictured above: a page from Phibbs' rescored work]: Britten would peer nervously over my shoulder (“please don’t be too taxing on the poor horn player…” he might say), though I took some comfort from what I’d read about his pragmatic attitude to instrumental writing. Shortly after the war, Britten almost singlehandedly created the genre of chamber opera in order that new stage works, in a financially crippled England, could thrive and be toured around the country. Later, he would adapt works by Purcell and others to suit particular events at Aldeburgh, and was himself working within tight limitations for the GPO film unit at the very time of Our Hunting Fathers.

What would Britten make of it all? I like to think that, despite some initial misgivings, he’d be delighted to see one of his most original and neglected early works take on a new lease of life. And for my part, if this arrangement introduces a wider audience to this extraordinarily powerful and relevant work, I’ll consider myself – at least partly – forgiven.

Add comment