A couple of hours of certainty really were very welcome during referendum week, and Murray Perahia did indeed bring clarity, poise, and an unquestioned masterpiece – Beethoven's Hammerklavier Sonata – to a full Barbican Hall last night. And not a single note of music written after 1893.

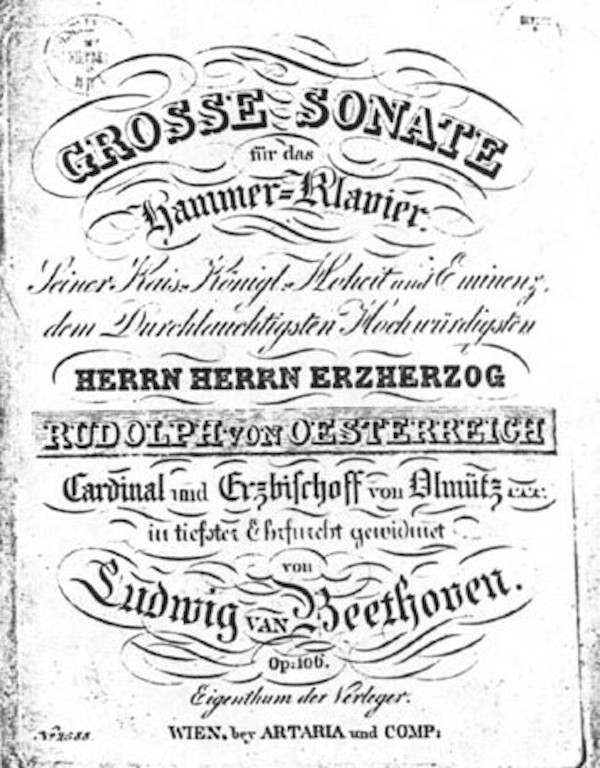

The finest moments of truth and revelation in this recital with a first half of Haydn, Mozart and Brahms, and then the Hammerklavier in the second, were the slow movements. There was a serene beauty about the A major Andante cantabile con espressione of Mozart’s A minor Piano Sonata, a very happy reminder of Perahia’s landmark recordings of the Mozart concertos from the mid-1970s. Later, the vast quarter-hour slow movement of Beethoven’s Hammerklavier (title page of the first edition pictured below; the manuscript is lost) was transcendent – a very great performance indeed. It had a natural flow to it.

These moments aside, the extent to which one enjoys Perahia’s playing, as the pianist approaches the age of 70 next year, is very much a matter of personal taste.

One of his marked characteristics is the way he uses rubato, lingers over cadences. He has described and justified this approach in a recent interview: “I feel music is always rhythmically dependent on voice leading. In other words, a rigid rhythm is not going to help the music because it doesn’t help the voice leading. If you have a suspension, you hold back a little until you resolve — it’s complicated.”

The search for balance and symmetry has its limits. This was evident from the opening work the Haydn F minor Variations. They started slightly ponderously, and at the end of each repeat, the brake was duly and consistently applied, the cadences stretched out, to underline the transition to the next variation. There was also to my ears an extreme reading the first of the Brahms Op. 119 pieces, the B minor Intermezzo. Perahia's delicate, almost obsessive contouring of the right hand phrases negated the bar lines, lost the natural lilt and the pulse of the 3/8.

Another defining characteristic of his playing is a tendency to iron out rhythmic irregularity rather than to bring it to the fore. There were moments when this brought astonishing beauty, such as the beautifully shaped, liquid flow of the semiquavers in the first movement of the Mozart A minor sonata. But the search for balance and symmetry has its limits. There are sections in both Brahms and Beethoven under the shadow of the Czardas, where unstable rhythmic flow is there to be highlighted eather than suppressed.

To me Perahia's playing, though persuasive on its own terms, can come across as unidiomatic. It leaves the impression that it is a deeply thought and personal approach to these works, but, perhaps in the final analysis, one that is too partial.

Add comment