Certain places and times are a vortex of creativity for music, collective fever points of innovation. Paris in the 1920s was one, New York in the 1970s another. Within a few years within a mile or two in Manhattan several music forms were essentially invented that went global – including disco, hip hop, punk and New York’s variant of salsa. It was also when the Minimalism of the likes of Philip Glass and Steve Reich began to find a large audience. As in Paris in the 1920s, uptown mixed it with downtown, the Talking Heads played art galleries and classicists hung out at CBGBs. In the middle of this mélange was one Julius Eastman, a composer who was also a choreographer and singer.

Eastman had some success at venues like The Kitchen, and his Stay On It was premiered in the UK the day after Steve Reich’s Clapping Music at the Royal Festival Hall in 1974, but seemingly he ended up (reliable biographical details in the latter part of his life being sketchy) suffering periods of homelessless, sleeping rough at times in Tompkins Park, taking drugs and abusing alcohol, while many of his manuscripts were scattered when he was evicted from his flat. He died in 1990 alone in hospital, of cardiac arrest, aged 49. A solitary obituary appeared eight months after his death.

How much of Eastman's work is lost and how much remains to be found?

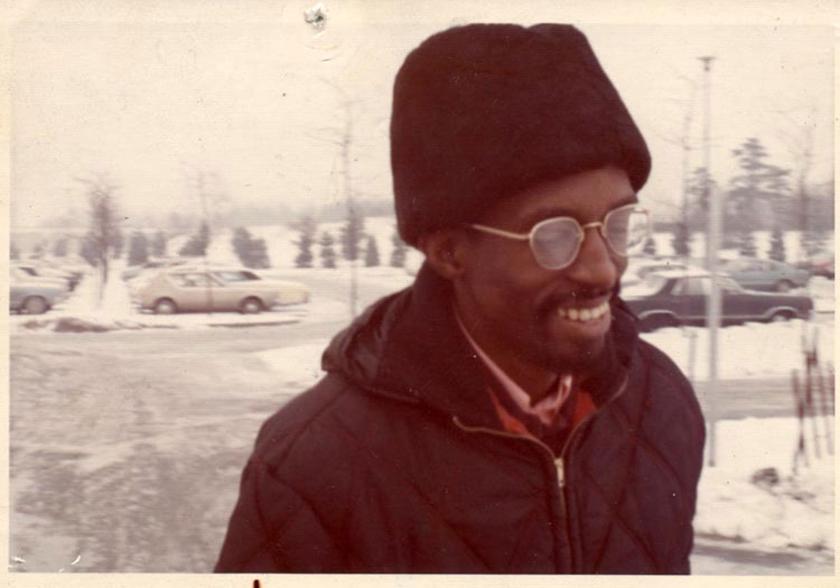

It wasn’t just because there was so much going on that he was overlooked (whole careers are dedicated to reviving lost African pop from the 1970s). He felt himself to be a misfit, declaring his ambition to be “black to the fullest, a composer to the fullest, a homosexual to the fullest.” It is fair to say that at the time both Punk and Minimalism were white forms. Rock may have developed from the blues, and Steve Reich may have studied in Ghana (and Philip Glass with Ravi Shankar), but the resultant Minimalism was initially austere and, unlike Eastman, containing almost no swing or funk. Eastman was kicking against the (white) pricks.

But the Julius Eastman revival is now up and running, partly due the considerable efforts of composer Mary Jane Leach. Albums have been released, and an article New York Times this October wrote of how he is “crashing the canon”. A significant boost was last weekend’s annual and ever-adventurous London Contemporary Music Festival, which was dedicated to his works and took place at Second Home in Holland Park (the venue where Antonioni filmed Blow-Up and which served as architect Richard Rogers's first offices). It had something of the feel of a 1970s New York art venue, complete with pre-Health and Safety sitting on stairs. A packed audience was drawn to a selection of Eastman's works, performed by Apartment House with guests, with some added poetry and a piece by fellow misfit Arthur Russell.

The event got under way with the reading by Christopher Kirubi of his own and others' poems, by turns tender and provocative, including one expressing a wish that there could be a gay or trans President, and another which celebrated oral sex with an angel. The evening’s finale of Eastman’s earliest piece here, 1973's Stay On It, was instructive in that there was an ecstatic, messy, organic element missing from, say, Reich's music of the time. It reached back to Terry Riley and La Monte Young and at the same time presaged post-Minimalism, making it feel way ahead of its time. The percussion-only ending of the piece could have been from Reich, but the rest was glued together with a seductive riff, more soul or latin music than anything from the classical world.

Another reason for Eastman’s lack of career progress was no doubt his provocative attitude – one of his most successful, fully realised pieces is entitled Evil Nigger, which requires a bold programmer for its title alone. That was performed on Saturday night (the LCMF series In Search Of Julius Eastman was a three-night event). An almost equally successful piano piece performed last night. Gay Guerrilla (see video, below) also dates from the late 1970s, when he really found his most distinctive voice, by turns playful and deeply elegiac, ending in cool transcendence. All the pieces here had a wonderful forward propulsion and energy, as opposed to the only non-Eastman piece on the programme, by his friend and colleague Arthur Russell (who also died young and whose career has been revived recently). The Russell piece, an excerpt from Tower Of Meaning, arranged by Kerry Young, seemed tentative and lukewarm in comparison to Eastman’s works. The most recent work of Eastman, Hail Mary from 1984 (a world premiere after it was recently found in a letter), felt like a fragment and a cry for help, a despairing prayer.

The event tantalised as much as satisfied – how much of Eastman’s work is lost and how much remains to be found? Can his choreography be performed again? At the very least, the enterprising LCMF made an intriguing case for a significant, overlooked voice. If only Eastman could have seen it himself.

- Read more New Music reviews on theartsdesk

- Watch the video for Julius Eastman's Gay Guerrilla, below

Add comment