theartsdesk in Bradford - Leeds International Piano Competition 2024 finalists shine in St George's Hall | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Bradford - Leeds International Piano Competition 2024 finalists shine in St George's Hall

theartsdesk in Bradford - Leeds International Piano Competition 2024 finalists shine in St George's Hall

A clear winner, but all pianists worked superbly with a great conductor and orchestra

How do you make a two-part final featuring five piano concertos work as a couple of totally satisfying programmes? First, give a wide list of concerto options, ask each pianist for two choices, settle on what will make the best contrasts – and then engage the brilliant Domingo Hindoyan and the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra of which he has been chief conductor since 2021 as partners

The fact remains that, despite differing levels of interpretation, the five finalists, all in their twenties, were as one with their fellow players and their conductor. It takes both elements to pull that off, but without Hindoyan’s constant conjuring of magic from his orchestra, the impact would not have been quite so dizzying.

Before a summing up of the finalists’ very different merits, though, why Bradford? Because the Town Hall in Leeds is currently undergoing renovation (earlier rounds were held at the university there, a stalwart partner). St George’s Hall (pictured below) was the first people’s pleasure palace to raise the tone of what was in 1850, according to my excellent guide to the best and worst of the city’s architecture, George Sheeran’s Bradford in 50 Buildings, “an unwholesome amalgam of factories, foundries, breweries, beerhouses, dram shops and poor back to back housing”.

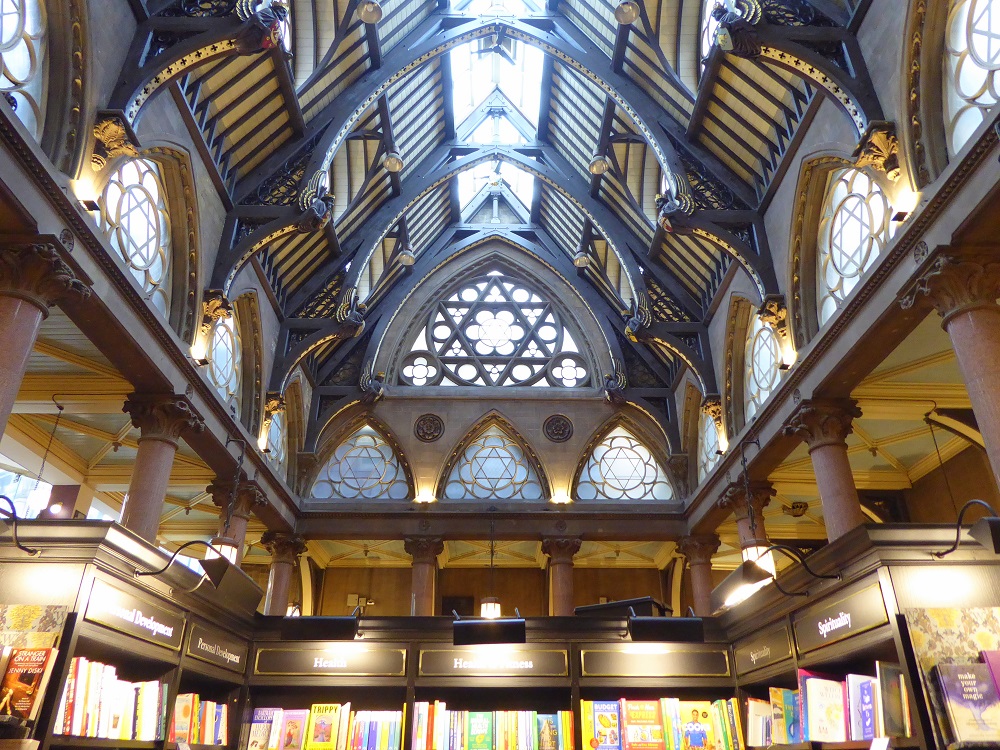

Other edifices converted to their former magnificence in Bradford include the later, Venetian Gothic style Wool Exchange by the same architects, now housing the most strikingly located Waterstone’s in the UK (pictured below). And if you think that’s not a bad bookshop, part of the jawdropping conversion of the main mill building in the model village of Saltaire, four miles from the city, has another, alongside huge exhibition spaces partly showcasing the works of Bradford lad David Hockney, whose financial support helped create a miracle (admission free).

Within St George’s Hall on Friday and Saturday, though, prosperity was on display. Glamour, too, given Hindoyan’s stylish conducting. Barbirolli may have been overstating the mark when he described the auditorium as the best in Europe; it’s a tad dry, but Hindoyan drew silky, atmospheric pianissimos from the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic. The first evening began with outsider (reserve list) British pianist Julian Trevelyan’s splendid choice of Bartók’s nostalgic swansong Third Piano Concerto. His handling of the first movement was too mezzo-fortist, not nuanced enough, but there was magical rapport with the orchestra in the American country idylls of the slow movement, and the quick-change dances of the finale all held together well. (Pictured below: the five finalists: Trevelyan, Khanh Nhi Luong, Jaeden Izik-Dzurko, Junyan Chen and Kai-Min Chang).  Like Vietnamese Khanh Nhi Luong, though, Trevelyan didn’t conjure sufficient tonal magic from the keyboard. With Luong, every element of Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto was perfectly in place, but the work needs a fizzing, occasionally reflective personality to match the composer's. The pianists who followed these two immediately showed more possibilities, Taiwanese-Chinese Kai-Minh Chang is a poet, allowing for total silence before the calm opening chords of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. The work struck me afresh – too often, it’s fine but routine – and that was as much the work of Hindoyan and the RLPO, sounding so natural in the first orchestral tutti.

Like Vietnamese Khanh Nhi Luong, though, Trevelyan didn’t conjure sufficient tonal magic from the keyboard. With Luong, every element of Prokofiev’s Third Piano Concerto was perfectly in place, but the work needs a fizzing, occasionally reflective personality to match the composer's. The pianists who followed these two immediately showed more possibilities, Taiwanese-Chinese Kai-Minh Chang is a poet, allowing for total silence before the calm opening chords of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. The work struck me afresh – too often, it’s fine but routine – and that was as much the work of Hindoyan and the RLPO, sounding so natural in the first orchestral tutti.

Luong’s successor, Canadian Jaeden Izik-Dzurko (pictured below in performance with the RLPO), found an upper-register brightness she’d missed. And he ran the total gamut of Brahms’s Second Piano Concerto, which if judged rightly shows ever facet of a pianist’s art – lyrical reflection, something of the thunder of the First Concerto and, in the finale, sparkling wit. Some would argue that Izik-Dzurko was too cool, but surely only in presentation; the actual results gave us both balance and excitement in a performance you’d be happy to hear in any concert hall in the world, complemented by the sheen and sweep of the RLPO, and consummate solos from principal horn and cello (sadly the players weren’t listed in the programme).  This grand finale left many of us in no doubt of who deserved the first prize. But there was also a good chance that it would go to the most audience-engaging of the five, Chinese Junyan Chen, who chose the unorthodox fireworks of Rachmaninov’s Fourth Piano Concerto (praise be, no Second or Third, no Chopin, no Liszt!). The vivacity was outstanding, but the greatest joint achievement of soloist, conductor and orchestra was to convince us that the noodling central movement can be profoundly involving with the right cowled colours and expressive intensity; what often sounds threadbare theme-wise came across as vintage Rachmaninov in its obsessive melancholy.

This grand finale left many of us in no doubt of who deserved the first prize. But there was also a good chance that it would go to the most audience-engaging of the five, Chinese Junyan Chen, who chose the unorthodox fireworks of Rachmaninov’s Fourth Piano Concerto (praise be, no Second or Third, no Chopin, no Liszt!). The vivacity was outstanding, but the greatest joint achievement of soloist, conductor and orchestra was to convince us that the noodling central movement can be profoundly involving with the right cowled colours and expressive intensity; what often sounds threadbare theme-wise came across as vintage Rachmaninov in its obsessive melancholy.

That was the big surprise of the two evenings, and given this year’s festival move to highlight gender equality, I wouldn’t have begrudged Chen the top place. But in the end the very distinguished jury – chair Imogen Cooper, artistic director Adam Gatehouse, Eleanor Alberga (whose Piano Concerto the 2021 winner, Alim Beisimbayev, recently premiered with Hindoyan and the RLPO), Mariam Batsashvili, Adrian Brendel, Sa Chen, Till Fellner, Ingrid Fliter and Pavel Kolesnikov – went for Izik-Dzurko, with Chen (pictured below) taking second place.  Trevelyan came fifth, Chang fourth and Luong third. I’d have reversed the order of the last two mentioned, but then I wasn’t present at earlier rounds, and have a lot of catching up to do watching the semi-finals, which matched solo repertoire (plenty of contemporary music, another vital emphasis) and chamber music with distinguished members of the Kaleidoscope Chamber Collective. Other prizes are listed on the excellent competition website, with plenty to watch; all I can do is repeat my gratitude for two evenings which worked dazzlingly well as concert programmes on the highest level.

Trevelyan came fifth, Chang fourth and Luong third. I’d have reversed the order of the last two mentioned, but then I wasn’t present at earlier rounds, and have a lot of catching up to do watching the semi-finals, which matched solo repertoire (plenty of contemporary music, another vital emphasis) and chamber music with distinguished members of the Kaleidoscope Chamber Collective. Other prizes are listed on the excellent competition website, with plenty to watch; all I can do is repeat my gratitude for two evenings which worked dazzlingly well as concert programmes on the highest level.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Add comment