When Riccardo Chailly (b 1953) left the Royal Concertgebouw for the Leipzig Gewandhaus, Richard Morrison said it was as if Bill Gates had ditched Microsoft for Aeroflot. The Gewandhaus has since become one of the lustiest of orchestral beasts in the world. Chailly and his orchestra make a rare appearance at the Barbican next Thursday and like all his previous visits it's likely to be a pretty unmissable event.

I met up with Chailly in 2008 in his vast Gewandhaus office that overlooks the square where the first stirrings of East German revolt were witnessed 20 years ago. Chailly became chief conductor of the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 2004 after a 16-year stint at the head of the Royal Concertgebouw. Before that, he had a spell at Bologna's Teatro Comunale and at the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra. He's also had a close relationship with La Scala since his debut there at 25.

We spoke about his love of contemporary music, his flirtations with rock and jazz, his stormy relationship with his father, composer Luciano Chailly, his disastrous 1985 debut at the Concertgebouw, his ringside seat at the Alagna La Scala walkout, how Karajan took him under his wing (and frightened the life out of him) and his concert at the Gewandhaus the night before, which included a blistering performance of Beethoven's Eroica.

IGOR TORONYI-LALIC: Your Beethoven last night was extremely fast, very vigorous.

RICCARDO CHAILLY: [Laughs.] It was. Yes... What we are trying to achieve with the Leipzig Gewandhaus - which has its roots in Beethoven’s time - is to do something parallel to what conductors with period instruments have attempted. That is to go back to Beethoven's score. Which is a very daring operation and a great challenge for this orchestra. Like Maestro [John Eliot] Gardiner would say, playing Beethoven’s symphonies, you choose to live dangerously. It is really edgy stuff. But the orchestra shows this incredible will to go with it.

As I was listening to the performance, I couldn't help but think about your love of speed. You used to own a motorbike and speedboat. You now ski. Do these things ever cross your mind when you're trying to blow wind into an orchestra's sails?

Well, this is a secondary thought. My fanatical relationship is to the text. I wanted to adopt the old Peters edition that contains some small differences to the later printed and critical editions. The tempi, so often discussed and criticised, are almost always extremely clever and not at all unrealistic or naïve, as is too often said. Sure, they are edgy, edgy to make your life impossible! But the music still has space to breath. Therefore you need to have the courage and focus to go with this. It is too easy to indulge in the traditional way, to say, it has always been done like that so let's continue and make everybody happy and leave everyone in peace, without any kind of turbulence.

Well, this is a secondary thought. My fanatical relationship is to the text. I wanted to adopt the old Peters edition that contains some small differences to the later printed and critical editions. The tempi, so often discussed and criticised, are almost always extremely clever and not at all unrealistic or naïve, as is too often said. Sure, they are edgy, edgy to make your life impossible! But the music still has space to breath. Therefore you need to have the courage and focus to go with this. It is too easy to indulge in the traditional way, to say, it has always been done like that so let's continue and make everybody happy and leave everyone in peace, without any kind of turbulence.

But it's not only a question of fast speed because when I conduct Mahler and Bruckner I tend to go the other way, to a slowness. The point is that the dramaturgical text of the Beethoven symphonies demands an edgy, dangerous way of playing. This orchestra is grenzenlos; it is boundless, border-less. Even when you think they might have these borderlines, they prove you wrong by playing Beethoven in a completely different approach, like this Eroica. Their capacities are unlimited. Two weeks ago we had a similar experience with the Fifth - another case of living dangerously, I assure you. I attempted to do the Fifth not only with the prescribed tempi but also, as it is written, with no rallentando whatsoever before the fermatas (pictured left: autograph score of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony showing no rallentandos before the fermatas). For over a century, it has been done the other way round. You cannot imagine how strong the struggle is to try to whip out the... I won't say bad habits but different habits, logical traditions that have been accumulated over a century. I feel it is about time to question those accumulations and introduce something different, something fresher.

People were saying last night that these were Toscanini speeds.

Well, Toscanini was unique. That was unrepeatable. Certainly in the 1930s he was pioneering Beethoven. Everyone knows the cycles of the 1940s and 1950s with NBC Orchestra. But much less is known about the early Beethoven cycle he did in the 1930s, though it is fortunately documented on live recordings. There you really see the courage of this man who must have been thought a complete nut. But when you go back to the roots of what the text dictates, then you get many answers in Toscanini’s favour.

You seem to balance textual faithfulness, however, with a spontaneity.

I'm trying to combine the two elements of music making. One thing I cannot do without is energy. You need the energy to describe your impulses. You need to give in your conducting gestures an impulse that includes the joy of music-making. If you don’t have this element - this eternal fire - then the whole thing has no reason to exist. Your eternal fire should be the fire that your orchestra has to express. So yes it was a pretty inflamed concert I have to say. I am still vibrating inside. This is what I have been trying years long to achieve: a balance between these two elements.

Let's go back to the beginning. Where did you get the bug to conduct?

Let's go back to the beginning. Where did you get the bug to conduct?

It was against the wishes of my father (pictured right: composer Luciano Chailly with Pope Paul VI). He had seen too much disillusion in his life as a teacher of young musicians who wanted to be conductors. My first teacher of piano thought I was a very talented pianist. But there was nothing that more bored me than playing the piano in terms of daily practising. I liked playing the piano but only for the pleasure of it. I hated the technical necessity of daily, hour-long application. Therefore, my fascination with conducting from an extremely young age was very clear to my piano teacher from the beginning - whatever my father, who was my first teacher in composition, thought.

I don’t recall when I first heard a live performance. Probably when I was eight or nine. It was probably one of my father's operas. I remember one very early rehearsal in the early 1960s in Rome, which had a big impact on me because this was a rehearsal of the Rai Orchestra of Rome in the Fore Italico. My father had no time to stay with me because he was working in Rai as a general programme office for classical music. He left me for one and a half hours in the rehearsal in the upper part of the Rai Rome hall in the last row. This was a rehearsal, I would discover later, of Gustav Mahler's First Symphony, at the time a totally unknown name to me, with a young Indian conductor making his Italian debut, Zubin Mehta. I will never forget the impact of that rehearsal. I analysed what I could - this was 1963 so I was maximum 10 years old, maybe younger – and I remember the indescribable feeling of hearing the spectrum of this gigantic instrument, the symphony orchestra. Since that rehearsal, I always thought that this would be the dream instrument for me to work with.

Did you practise conducting at home?

I did. While my fellow friends were playing football I was listening to opera recordings, my father’s collection of old records, and sweating in my room conducting in my own way - which way, I don’t know. I was also spending hours and hours studying and listening. My parents were extremely worried. They said that there must be "something wrong with our son, who stays indoors instead of doing sport and being in the open air with the other kids, playing tennis or football". My early interest in music provoked not a little worry in my parents.

And there was an interest in jazz then too.

At that time, yes.

Was there an equal fascination?

Equal, no. I always had a tremendous attraction to classical music. Though always a music with borderlines. I had no preconceptions, no prejudices or ideas about genres, about classical music, jazz, rock, whatever, country music etc. There were no barriers for me. I was totally ready for the musical universe. That of course brought me to playing the guitar, electric organ and the drums. I experienced being in a rock band, singing and playing along with these three different instruments. This was devoted to the summertime where I wanted to have this special experience with friends. Regularly every summer we would meet and play together.

Were there any recordings of you singing?

Were there any recordings of you singing?

No. Public performance, yes. In dancing clubs, yes.

Then you landed this incredible job assisting conductor Claudio Abbado.

That was when I was still a student in the conservatory of Milan. It was a great day for me when Claudio called. Not only was I able to be close to him daily at work in La Scala, but he also gave me the chance to work often with the La Scala orchestra, to prepare programmes of his, as well as of those of the guest conductors. That gave me the opportunity of listening to the rehearsal of some of the greatest conductors of those years. I cannot forget Claudio in primes when he did the Brahms Cycle or when he did the contemporary music of Luigi Nono. But I also met figures on the podium like Barbirolli the year before he died. I remember asking him, "Maestro, could I do anything for you? Could I rehearse for you?" He said: "No. But you are welcome to stay in my rehearsals." He was doing Mahler Five. It was an unforgettable experience.

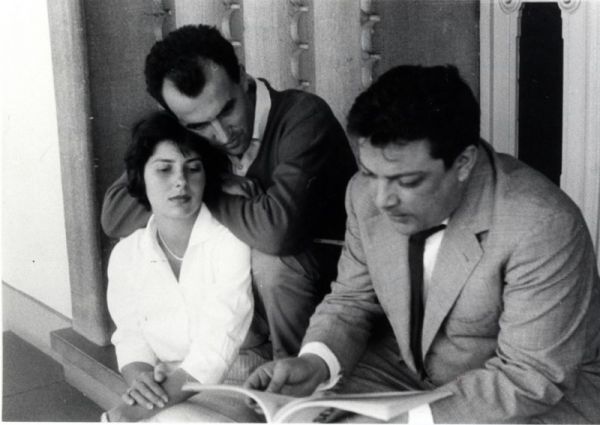

Another man I will never forget was Bruno Maderna (pictured left: left to right, Nuria Schoenberg, Luigi Nono and Bruno Maderna); he guest conducted there. I remember a Schubert Maderna programme. Those were unforgettable things. When Seiji Ozawa came in at an early stage and conducted Mahler Eight. It was part of the complete cycle Abbado wanted. And this was for me an icebreaker in the universe of the vocal Gustav Mahler works. I was absolutely overwhelmed when I slipped out into the night to discover such a miracle existed. It’s full of memories for me those years.

But it must have been terrifying. You were just out of your teens. Then you had your professional debut at 21 at the Chicago Lyric Theatre and at 25 you debuted at La Scala.

I am probably the youngest to have conducted at La Scala. It was unnatural. I always say that I have no regrets about all the many things I've done except that I sometimes feel that the major issues came to my life too early. That includes in my private life. My first marriage lasted three years, which is not by chance; it came in life too early. Things like my La Scala debut or my other debuts in England with the LSO in the 1970s or at Covent Garden very early in the late 1970s. When you are a kid still, doing this pushed me through the barrier of doubt. Should I or should I not? There was no time to think. Just go. Take the chance and see how it goes and try to do your best. It was not always right to say yes.

But I think you have to have the courage to do these things. I remember Maestro [Wolfgang] Sawallisch telling me one thing: "Remember Chailly, you should try to make all your debuts in opera, chamber, orchestral, choral before you're 50. If you dare to do that, you will always have the benefit after 50 to correct your mistakes. If you don’t do that, you will miss your chance." At the time, I thought this was a bit dogmatic. Thank you for the advice, Maestro, I thought, but is it that serious? Now I’m 55. And bloody hell, if I look back, how right was the advice of Maestro Sawallisch. I really see the benefit having done the mistakes and having taken so many risks.

Herbert von Karajan took you under his wing too.

Herbert von Karajan took you under his wing too.

This was a great joy and privilege to get to know Karajan in the last five or six years of his life.

And I read somewhere that he would sometimes turn up unexpectedly at your concerts and flumux you.

It was so difficult, especially when I was with the Royal Philharmonic in the Philharmonie. We are talking the early 1980s. I was still young (pictured above right: a young Chailly). I was about to start Strauss's Don Juan and who comes to see me while the orchestra was tuning up? Karajan. Who I had never met before. "Maestro! How nice to meet you. What an honour. What are you doing here?" [Chailly says through clenched teeth] "I’m going to listen to you?" he says. "What?!" "Yes!" he continues, "What are you conducting?" "Unfortunately, Strauss's Don Juan, one of your pieces." [Laughs.]

Another time, he came backstage to where there is a small space to watch the performance through a glass door. The stage-hand people thought, oh, he wants to walk through, so they opened both doors. And there he was. The public saw him - because everything was quiet - and a big applause started in the hall. I thought, why did they have to do that. Shit! I have to come out now and conduct. And then Karajan said, "Was machen sie das?! Ne. Bitte, nicht..." And they closed the doors. So it was like a vision of Karajan. Applause. Close doors. And with this I had to go and conduct. The next morning, 9am, he calls. "Maestro, I want to talk to you," he says. I thought, this is the end! But strangely enough the comments were on the positive side. He didn’t know the Royal Philharmonic at the time. He was telling me interesting comments, positive comments, about the concert and also about the rest of the programme.

And you were soon invited to Salzburg, becoming the first Italian to do so.

Then we met regularly in Berlin. I had the privilege to be allowed to listen to his rehearsals and recordings. And very soon after that came my debut at Salzburg in 1984. He wanted me to open the season with a new production of Verdi's Macbeth. That was as a consequence of this Berlin anecdote.

In 1988 you began a hugely successful 16-year tenure as chief conductor of Amsterdam's Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra. But your 1985 debut wasn't so auspicious.

There was a bit of an empty hall. You would have thought that this was the most disastrous concert of anyone's life. In a hall of 2,000 seats, I remember 150 people. I had programmed three very interesting different generation 20th-century Italian composers: Berio, Bussotti, and Petrassi. Strangely enough it was something that turned on the orchestra. And they asked me to become their music director.

The Concertgebouw used to be a pretty traditional orchestra. Didn't your interest in slightly obscure 20th-century repertoire concern them?

They wanted it. They wanted this contemporary shower programme. Perhaps because I did it with total belief and devotion. I love to do contemporary music. It is one of the reasons for me to be a conductor. It wouldn’t make sense enough for me to just perform the classic repertoire without having the constant possibility to perform new music. And they felt that they wanted to change their own repertoire and their own identity into something more contemporary, something more linked to the new music. This was a very important point when they appointed me.

There were some brilliant recordings made from that era. But then you moved to the Leipzig Gewandhaus and some didn't understand what you were doing.

Yes I remember. "Chailly’s collapsing!" [Laughs.]

Someone said that it was like Bill Gates going from Microsoft to Aeroflot.

Someone said that it was like Bill Gates going from Microsoft to Aeroflot.

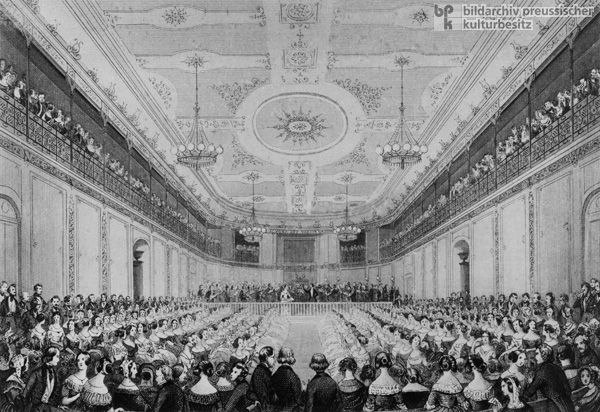

I am up to date with those things. I have to say, it was not very well received from an orchestra that is one of the oldest in history (pictured above, the original Leipzig Gewandhaus hall). This year is its 228th anniversary. So things should be looked at in the right perspective. First of all, the reason why I'm here is as a consequence of Karajan. Because Karajan wanted this combination - Gewandhaus and Chailly - in Salzburg in 1986. I had not even thought about it. But he spent an afternoon telling me a great deal about the orchestra, the sound, the identity, the tradition and history that had played such an unavoidable part for Germanic culture. It is after all considered the mother of all symphony orchestras. Karajan had an enormous respect for it. Therefore he wanted this to happen. That was the turning point between me and the Gewandhaus, but it was exactly the time I took over the Concertgebouw.

They kept for years asking me and I was never available to take it up because of my commitment in Holland. Up to 2001, when I decided to guest-conduct the orchestra again here in the Gewandhaus and I found the same warm, bravura playing, the same fascinating sound, their own discipline, their own human warmth, untouched from my years there in 1986. That concert provoked the whole thing to be asked again: would I be the new Gewandhaus Kapelmeister? That was a crucial moment when I had to decide whether to stay another period of time in Amsterdam or not – because it was getting close to 16 years there. And the idea of an orchestra that had this broad besetzung, the largest orchestra in the world, 185 musicians. In the DDR it was 200. Because we are serving, weekly, the opera house, the Gewandhaus and the Thomaskirche [where Bach was Cantor]. We need to cope with the demand of a whole city. So an orchestra that plays the whole year operatic music, symphonic, Baroque - especially the music of Bach - is something unrepeatable in the world. And that’s the point that I wanted to stress when I took over. The role that Leipzig had played centuries long. When you speak to Henze he always reminds us that this was the city of reference for what musical activity in Germany was, more than the great capitals.

Even in the DDR?

Yes. This makes this city unique even today. This was the reason. Of course the outside world does not know how much is going on here and in which way and at what level. That's understandable. But for three years we have been undertaking an intense line of touring. And the success that every concert abroad provokes brings back the subject of the reason, why are we making music together? But this time without the question mark.

Everyone's said you've transformed the orchestra. Was the orchestra that you took over in poor shape?

No. Maestro Blomstedt who stayed before my time for seven years at the helm left me the orchestra in the best shape. He's an excellent orchestral trainer. He was working with all the sections to deliver an orchestra in the best of form. This is exceptional. Normally in the world of music, the delivery between chief conductors is not this way. Normally it is the other way round. It can be embarrassing, disappointing and easily come to polemics.

You must be a good negotiator, too. Because in March 2009 it will be the first time that the Thomaskirche choir [Bach's choir] goes on tour.

You must be a good negotiator, too. Because in March 2009 it will be the first time that the Thomaskirche choir [Bach's choir] goes on tour.

That will be difficult to repeat. When we come to London we have three choral programmes, which is a very original thing. On January 1 [2009] it will be Beethoven's Ninth. Curiously enough the Barbican asked me to conduct the work twice. But I thought this would be a bit extreme. For a week I thought about it. "We'll give a couple of hours in between the two performances," they said. But I think the Ninth has so much emotional power that to do it twice and to be able to recharge in between would be very difficult.

And on January 1 as well.

Will have done it three times already of course. Because that maestro on the left [he points to a photo of a stern-looking man with a broad moustache] is Arthur Nikisch (pictured right: former chief conductor of the Gewandhaus). He wanted this tradition of doing the Ninth on December 29, 30 and 31 every year. So this is a major tradition.

In spring [2008] you had a spat with the opera house over the appointment of controversial theatre director Peter Konwitschny and you ended your relationship with the opera house. Why did they decide to appoint him without telling you?

That was a secondary reason actually. There were two or three reasons. I'd say the Hausregisseur [company director] was the third reason. The first reason was the success of this orchestra on tour. Which was so tremendous that we had to give more to that activity. There's so much demand over the next few years that we have to add extra weeks. That means I couldn't any more maintain the music directorship of the opera house even though I was doing only one opera every year there. I wanted to do at least the minimum given the amount of weeks I spent in the symphonic field in Leipzig. Reason number two was that I had a cardiological problem in January, which was a warning. I had to watch how much I was doing during the year. My Doctor said things are under control but that this was a warning, you should balance things, do less, instead of more. Point number three. They appointed this Hausregisseur, Konwistchny. A person I do not know. So I don't want to even start to judge him. But the procedure I found untakeable and wrong because it might not have worked and he could have been a disaster because of not knowing the person. Therefore I decided to interrupt my opera relationship. At the moment I have prolonged my Gewandhaus relationship to 2015. So in one sense there is a sign of withdrawal, on the other, a will to continue to the future. That is the situation.

What is your view of modern opera directors? Your good friend Franco Zeffirelli was very rude about them recently in an Italian newspaper. Do you agree with him that they are often too vulgar and incompetent?

What is your view of modern opera directors? Your good friend Franco Zeffirelli was very rude about them recently in an Italian newspaper. Do you agree with him that they are often too vulgar and incompetent?

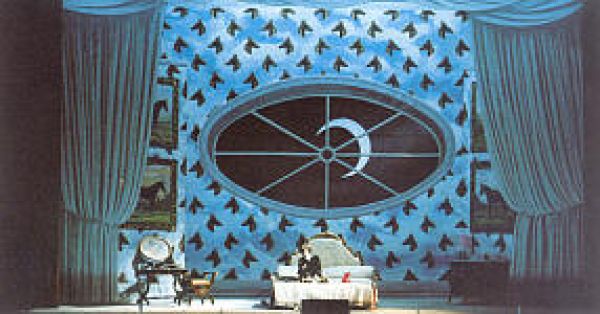

It is a matter of aesthetics and quality. I remember my experiences many years ago with Ken Russell doing The Rake's Progress, which at the time was a revolutionary performance in Firenze (pictured left: Russell's Rake). I remember the two Puccinis with Niklaus Lehnhoff in Amsterdam, Tosca and Turandot; staggering performances with new concepts of opera direction. I did have wonderful results out of those experiences. In Leipzig we had something else. They were more in traditional direction. But what I remember in these three years with the opera house is an excellent orchestra, excellent chorus.

You are famous for having one of the widest repertoires of any conductor working today. You can juggle anything from Rossini operas to Edgar Varèse. How?

I don't know. I know only that I am the only Italian conductor to have ever recoded the Bruckner cycle.

And a very good one.

Well, I don't know about that. But that was a Guiness Book of Records moment in the world of Italian conducting. I was told that by a music critic from Rome.

You haven't spent much time in Italy. Why?

This was just how my life went. My first orchestra was in Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, where I was for eight years and they were unavoidable years to build experience of repertoire as chief conductor. I couldn't have done the Concertgebouw without those precious eight years in Berlin. But I've been doing so much in last 20 years at La Scala when I look back. It has been a regular guest conducting slot in a very intense way with La Scala Philharmonic, including international touring. Berlin, Amsterdam and now Leipzig have been an unavoidable possibility of me continuing along the provision of a distribution of my work in terms of repertoire. I don't think I want to stop expanding my repertoire. Now I'm breaking my brain about Bach's Christmas Oratorio, which I will conduct in Italy, Venice, Zurich Opera, Firenze and in 2010 Leipzig. It's a major step forward for me after the two Bach Passions. This will be my fourth major Bach project with the B-minor Mass. The more I go backwards in terms of compositions the more time I need. It's a long and slow process.

Are you sad that you never got the chance to head up La Scala?

Whenever I'm asked this question I ask the interviewer, would you mind spending some time checking what I did there and how much I did there? It's amazing the amount of things in opera and symphonic music I've conducted at La Scala. It was so beautiful, so fun. In fact in the next years I will not conduct opera in Scala again because I did so much. I like now to concentrate on Leipzig.

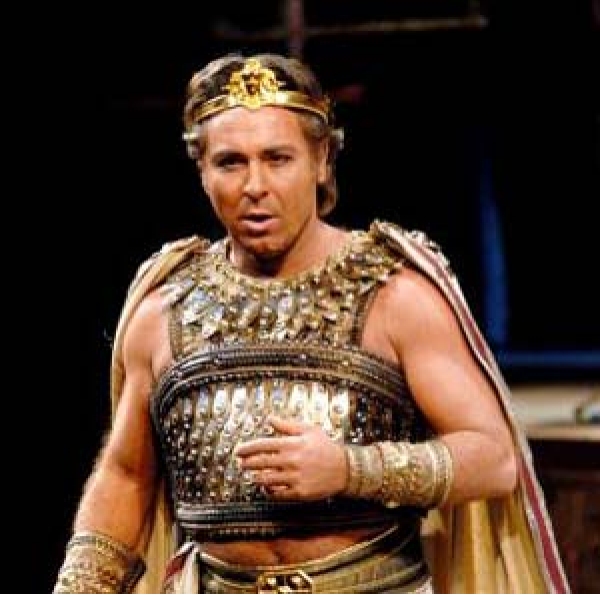

You were conducting during Roberto Alagna's famous La Scala walkout (pictured right: Alagna as Radames in Aida). Had that ever happened to you before?

You were conducting during Roberto Alagna's famous La Scala walkout (pictured right: Alagna as Radames in Aida). Had that ever happened to you before?

No and I hope it won't be repeated. Because, I tell you, it was completely amazing. You won't believe your eyes. The great thing was that we already felt from the previous performances that something in this direction was going to happen. Roberto had given a kind of warning. So somehow we had the substitute tenor on stage that night but without the dress. And it came to the point where he had to be kicked, physically kicked, onto stage in... he was wearing an Armani black shirt I remember.

Physically kicked because he was too nervous?

Physically kicked on to stage. And the other one [Alagna] disappearing. And to my great amazement I could continue without stopping the orchestra. It was unbelievable.

And yet the DVD still came out with Alagna.

Roberto had an over-excessive reaction to this. He did a good performance of it in his own way. He expressed vocally many things in this performance. So I'm glad there is a document that proves that it was a good Radames.

You're surprisingly little known in Britain. Many of us think you should be far more well known here. Do you think you should have done more guest appearances to build up your profile here?

I did an enormous amount of guest conducting in London when I was young in the 1980s with the London Philharmonic and Royal Philharmonic. The London Symphony was the orchestra of my British debut in 1979 at the Edinburgh Festival. I will never forget the beauty of sound and their fast way of working. I hardly think there is an orchestra in the world that can learn a piece faster than the LSO. And how sympathetic an orchestra too. Yesterday I had on my table an official invitation to guest with LSO from Valery who is a dear friend. So things are under consideration. Let's see if we could build something again.

You have an almost unique love of contemporary music among the star conductors. Did that come from your father?

Probably, yes. Contemporary music was a daily element in my family. At night time I was falling asleep listening to my father composing operas at the piano - he composed 14 or 15 operas and a lot of contemporary symphonic music. The language of contemporary music was part of my day. He was an excellent teacher also I have to say.

But then you didn't talk for a while. Why?

That is typical really. In a way to be a pupil and son is an awful dichotomy. It is a quick way to have family troubles. But also this was to do with character and personalities and personal stories which pulled us apart for some years. In the last part of his life things were much better for sure.

Do you now live in Leipzig full-time?

Not full-time. Months here every season are divided by weeks in Rome for a breather.

A few years ago you stopped motorcycling because you nearly had an accident. But you started speedboating and skiing.

When I can do this ascending parachuting on the sea, I like it very much. I was doing that in the Cote d'Azur, where there are beautiful places to do it. Now it's three years since we bought our house by the sea in Genoa where there are no facilities to do this, so I haven't done it for a few years. My wife is very happy; I am very unhappy. The feeling of flying is unbelievable. You are carried by the motorboat but you are 50 metres higher, above the earth, above the sea. You see this enormous landscape of water and the coast wherever you are. And you only hear the noise and power of the wind. It's an indescribable feeling.

Add comment