Is Steptoe and Son the platonic ideal of the British sitcom? Two men trapped in eternal stasis, imprisoned by class and bound together by family ties as if by hoops of steel, never to escape: it’s what half-hour comedy should be. Posterity would seem to agree, because since the sitcom ended in 1974 the two rag and bone men have never been out of work, appearing in the cinema, on stage and radio. For 30 years they made and reran the show on Swedish television, underpinning the widely held theory that Steptoe is but a step from Strindberg.

Half a century after its creation, last summer Steptoe and Son dragged their horse and cart down to Cornwall, home of the experimental company Kneehigh. Their adaptation of four episodes of the show for the stage has now pulled up at the Lyric Hammersmith. When director Emma Rice sent Steptoe’s creators Ray Galton and Alan Simpson the script, the opening page proposed to introduce a sort of female guardian angel who would allow audiences to see father and son through “the lens of femininity”. She didn't mention that her cast would use Cornish accents. So this incarnation of Steptoe and Son is certainly different.

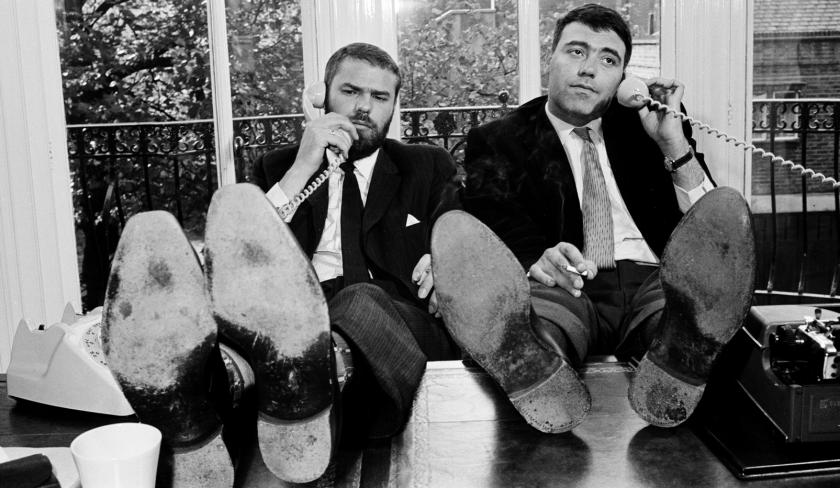

The episode Rice begins with is “The Offer”, the first ever Steptoe script, which was written as a one-off for Comedy Playhouse in 1962. This was a series gifted to Galton and Simpson after years of sterling service writing Hancock’s Half Hour, from whose star they had just acrimoniously split. Steptoe and his son Harold, played by Wilfrid Brambell and Harry H. Corbett (pictured below), took up residence in Oil Drum Lane for the next three years. The show came to a halt in 1965 and then returned in colour for another four years in 1970.

I meet the two great masters of television comedy in Ray Galton’s splendid Georgian home next to Bushy Park in south-west London. Portraits of the pair – paintings and photographs - fill the hallway. Now both in their early eighties, they’ve known each other for 65 years, having first met in a TB isolation ward as teenagers. Both long since widowed, they complete each other’s sentences.

JASPER REES: Could you take us back to the moment these two men sprang into being?

JASPER REES: Could you take us back to the moment these two men sprang into being?

ALAN SIMPSON: We were stuck for an idea for show number four in Comedy Playhouse. To pass the time I remember coming up with ludicrous ideas just to make us laugh. It was always two of everything. Two rat-catchers in Buckingham Palace. Ray said, “Two rag and bone men.” I went, “Oh yeah...” I didn’t realise he was serious. I thought he was joking. I couldn't think of anything myself and suddenly I thought, "What about these two rag and bone men?" He said, “What about them? I thought you didn’t like the idea.” We were getting to the stage where we had to start writing something. I said, “Let’s give it a go.” So we started writing. We didn’t have any names: first rag and bone man, second rag and bone man. Ten pages of arguing. They’ve come in off the round. It was flowing very nicely. We got what would have been halfway through the script and we couldn’t go on like this for half an hour. So we had to decide who were they, what they were doing and what their relationship was, were they brothers, related in any way? It was obvious one was older than the other and the one who stuck in the yard was moaning because he couldn't get out and about any more. And then the idea came they were father and son and that solved everything. If they’d just been cousins or even brothers it wouldn’t have worked, or not in the same way. And it was the fact that the younger one was 37. He wasn’t 27. He was 37 and he was trying to get away. As soon as that crystallised we finished writing the script.

We found that sometimes it’s a blessing to be restricted

Who came up with the name Steptoe?

RAY GALTON: We both used to spend a lot of our time in Richmond in a gang of guys. We had a place we rented and we all used to congregate there. There was a place opposite.

AS: A photographic shop that sold old cameras called Steptoe and Figge.

RG: We didn’t want Fygge.

AS: The idea “and Son” had already occurred to us. Dombey and Son. We tried Figge and Son. Steptoe and Son? Ah that’s it. I always said two syllables is better than one.

RG: We knew when we finished it that it was good. Tom Sloan - [the BBC's head of comedy] who had given us this marvellous opportunity to write what we liked every week, cast it, be in it, direct it, everything, which had never happened before to writers and never will again I’m sure - first came down to rehearsals and was saying, “You know what you’ve got here?” We were playing it dumb. “No no no, what Tom?” “It’s a series.” After 10 years of doing Hancock, this star vehicle, we had different actors every week and thought, we don’t want to go back on that treadmill again. In the end we ran out of excuses but played our trump card. We said it, “If Harry Corbett and Wilfrid Brambell want to do it, we’ll do it.” Thinking, they’ll never want to do it. They jumped at it. It was a big hit and right after the first series the BBC repeated it immediately, which is very unusual. To had a run of 12 weeks instead of six.

'You dirty old man': Harry H Corbett as Harold Steptoe

AS: We’d just come off nine years of working with Hancock and we thought it would be like a breath of fresh air to have the world as our oyster. The problem as we found out very quickly is when you can pick from anything it’s very difficult to choose what you want to do. And we found that sometimes it’s a blessing to be restricted. At least it gives you parameters to work within.

Why did you alight on those two actors?

RG: We knew exactly the actors we wanted. Harry Corbett was a method actor and was an actors’ actor. They used to rush home to watch him on telly. He also had a group called the Langham Players on radio, and of course he was Joan Littlewood’s crown prince at Stratford. Wilfrid Brambell we’d seen in Shaw plays and Clive Exton’s plays. We said, “Could you put out an availability check for them?” Corbett was down in Bristol Old Vic doing a Shakespeare and the old man I don’t think was working at that time. The script went down to Harry and he read it - "Oh, god, must do this" - and managed to persuade the Bristol Old Vic to give him a week off. We had other people in mind if they hadn’t been able.

Can you remember the impact of "The Offer"? How did it go down out in the real world?

AS: It was certainly different to anything we’d done. It was more of a drama than a comedy. When we got into the studio there was a wonderful set. And Harry H. Corbett said, “Never mind the set, what are all these seats doing here?” We said, “That’s for the audience?” he said, “Audience? Nobody told me about an audience. I’m going to have to rethink my entire performance.” And we thought, "Christ, we’ve got an actor here." Harry played it as a drama.

Real tears, that’s the point. Comics wouldn’t have done that

He famously and – unprecedently for a comedy - cried at the end.

RG: I remember at the end of "The Offer" when Harold says to the old man he’s leaving, he can’t stand any more of this, and he starts loading the cart up with his few possessions, the gold bag with one golf stick in it, things like that, and when he was ready for off, “I’ve got to go, Dad, I’ve got to go”, and then he goes to the stables to get the horse out and the old man says, “You can’t have the horse, that’s mine, you can’t have that.” So he gets between the shafts himself and starts to pull it and he can’t move. And gradually he starts to cry. And he did cry. And the old man says, “Don’t go now, son, go in the morning. Come in and I’ll make you some coffee. Go in the morning, there’ll be less traffic about then.” And he takes him into the house, Harry still protesting about how he’s going – “I’ve got to go.” And the door closed and the old man came out and nicked a barometer or something that he coveted and took it into the house. When Harry started crying I thought, “Oh my God, we really have got actors here.”

AS: Real tears, that’s the point. Comics wouldn’t have done that. We loved it. It enabled us to do subjects which you couldn't do with comedians. For example we did one called "Steptoe and Son and Son" where a girl turns up on the doorstep eight months' pregnant. In those days you couldn't have that with Hancock or Frankie Howerd. They weren’t allowed to have sex lives. Nowadays it’s all changed.

Was the sadness something that you built into it from the very start and talked about with each other?

AS: We didn’t have to do out and out comedy for the sake of it. This is all part of the terms of reference of Comedy Playhouse. We could do what we liked. We could do a comedy that wasn’t all about laughter, that had something else in it, and you could go a page or two without a laugh and have nobody looking to see where the next funny line is.

How long did it take you to write an episode?

RG: We allowed a week to do it. We’d start beforehand and may have three or four in hand when you start but round about episode four or five you get caught and they’re waiting for it.

Why did it end?

RG: We ended it twice. Once for real and once for four years. We just thought, that’s it.

AS: A lot of things had changed. Colour had come in. People said, “That’s going to ruin it.” Completely wrong. It made it look even more grotty. Both times we thought we’d exhausted it and started repeating ourselves. The second time they hadn’t fallen out but the relationship was getting a little bit frayed around the edges and apparently in Australia it collapsed entirely. But we weren’t party to that. They were touring a cabaret script that we’d written and they brought in songs and dance routines.

RG: They were probably a bit fed up with each other.

AS: They had different approaches as well. Harry was always more of a method actor whereas Wilfrid was the old-fashioned learn-the-lines-and-say-them type actor.

How much involvement did you have with the BBC drama The Curse of Steptoe, which argued that Harry H Corbett felt imprisoned by the role of Harold Steptoe and detested Brambell? (Pictured: Jason Isaacs and Phil Davis as Corbett and Brambell)

How much involvement did you have with the BBC drama The Curse of Steptoe, which argued that Harry H Corbett felt imprisoned by the role of Harold Steptoe and detested Brambell? (Pictured: Jason Isaacs and Phil Davis as Corbett and Brambell)

AS: We had a day here with the writer and the producer and gave our side of the story and they took no notice of it. It was totally untrue. It’s quite well written, extremely well played, but it wasn’t true, none of it happened – not as far as we were concerned. They had it that on the first day of rehearsals they couldn’t stand the sight of each other from the word go. Totally untrue. On the contrary they got on like a house of fire. Wilfrid admired Harry and Harry admired Wilfrid. Two totally different types of actor but Harry used to direct Wilfrid.

So it was seen through the prism of that Australia tour.

RG: Which was so long after it. They must have been aware they were getting near the end of their careers.

You felt trapped into doing it, the characters are trapped. Did Harry H. Corbett feel trapped by the role in the way that the drama suggested? That he wanted to be a serious actor and he ended up being a vaudevillian?

RG: The funny thing with Harry was his accent and when he did "Now is the winter of our discontent" he would sound like Steptoe doing it. And people laughed.

AS: Before when he did it they’d think, "What an interesting reading." But after Steptoe it was, “Ah it’s Steptoe doing Richard III.” His natural accent was Mancunian and the old man was from Dublin although he’d lost his Irish accent. We saw Harry played an American once and he sounded like Steptoe doing an American accent.

Did it in any way irk him?

AS: I think he was very philosophical about it and he decided to milk it.

Wilfrid Brambell pays tribute to the late Harry H Corbett

Did you ever come across anyone saying, "That’s my life you’ve put on the telly?"

RG: We got a letter from the Federation or Iron and Steel Merchants representing rag and bone men saying how much they enjoyed the show but would we take heed that our prices are way out and the rag and bone men are saying that all their customers are complaining because Steptoe and Son pay much more for old junk than they do. We did take it to heart.

Did you feel like sadists keeping Harold there? You inflicted pain on this character for many years.

AS: We never made it clear to ourselves even whether Harold stayed because he felt that he owed a responsibility to his father or the fact that deep down he was incapable of going out and fending for himself, and he used the father as an excuse not to have to prove himself. In a way we sided with the young man. We used to make the old man more of a bastard. When he’s won again he’s “got him again”. If we wrote it now we would side with the old man. In those days we were younger than the young man.

RG: He desperately wanted to leave but he didn’t have any faith in himself. Nothing going for him outside in the big bad world. He would pick on all the things he couldn’t possibly do or be now: just leave home and be a scientist or a doctor. He was driven by fantasies, but it was desperation. He really wanted to go.

AS: In some respects it was an extension of the Hancock character: daydreaming and delusions of grandeur. The only thing is Hancock was more pompous and more middle-class.

Did the situation grow out of post-war changes and the growth in social mobility?

AS: He was aware that there was a world out there he was missing out on. But the whole point about it is there was no social mobility for them. Mobility for them was get on the horse and cart and go out for a couple of hours.

How much did you know about rag and bone men?

RG: The family next door to me, the father worked very hard for himself but he didn’t have a job. His son was about the same age as me had a horse and cart and I went out with him a few times until my mother found out and I got a right walloping. If you asked people about rag and bone men, they’d probably think they were all owning a fortune. Like you mustn’t give money to beggars in the streets because their Rolls Royce is waiting round the corner. We all believed that all these people were just scrounging off of us. But it was breaking down. By the time rock’n’roll came in Britain was a different place.

AS: You used to have rang and bone men going up the King’s Road when I was a kid. What Steptoe is about is summed up to a certain extent in the end of one of the scripts that Emma Rice has picked for this play. We called it “Two’s Company”. The old man goes out every week down to the bingo and he’s met a younger woman, about 20 years younger than himself, who goes there to provide the teas, and he’s started taking her out. When they get back home he introduces her to Harry and they can’t believe it: she used to go out with Harry 20 years earlier. Harold was very much in love with her and she left. We get as much out of that situation as we can and right at the end the two of them are arguing and when they stop they look around and she’s gone. A little note that she’s left: “I can’t marry you, Harold. You’re already married.” And the old man says, “What does she mean by that, silly cow?” And they both start insulting her. “Didn’t see much of her anyway. See the size of her legs?”

AS: You used to have rang and bone men going up the King’s Road when I was a kid. What Steptoe is about is summed up to a certain extent in the end of one of the scripts that Emma Rice has picked for this play. We called it “Two’s Company”. The old man goes out every week down to the bingo and he’s met a younger woman, about 20 years younger than himself, who goes there to provide the teas, and he’s started taking her out. When they get back home he introduces her to Harry and they can’t believe it: she used to go out with Harry 20 years earlier. Harold was very much in love with her and she left. We get as much out of that situation as we can and right at the end the two of them are arguing and when they stop they look around and she’s gone. A little note that she’s left: “I can’t marry you, Harold. You’re already married.” And the old man says, “What does she mean by that, silly cow?” And they both start insulting her. “Didn’t see much of her anyway. See the size of her legs?”

Why has the show stood the test of time?

AS: I think it’s because it’s about a situation, a relationship that has no time setting. It’s as old as the human race.

There have been many versions of Steptoe, most overseen by yourselves. What did you make of the approach from Kneehigh? (Kneehigh's Steptoe and Son pictured above by Steve Tanner)

AS We were intrigued more than anything. It didn’t occur to us that it could be used in that sort of production. She said that it would be a new slant and she’d like to use our scripts as a basis. She picked three or four scripts and stitched them together. It would be her view of the relationship. We were happy to let her do it. It’s very flattering when people who have got such talent are interested in your work, albeit it’s 50 years old. She sent this treatment and it was even more fascinating because it was something we would never have done. She’s brought in an extra character, a guardian angel type thing in and out of the narrative in different guises, different ages, and she’s brought music of the time in. She’s just turned it into a musical version and a female view. This character comments on the relationship between two men. We’ve never looked at it that way. The nearest we got is the failed romances with Harry and one or two with the old man.

RG: I don’t think we would have allowed anybody else to bugger about with it like she is. But that’s what’s making it interesting.

What did you both think when you read the phrase, “the lens of femininity”?

AS: Hello, we’ve got an intellectual here.

Watch the whole of 'The Offer'

Add comment