The Secret Life of Rubbish / The Toilet: An Unspoken History, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

The Secret Life of Rubbish / The Toilet: An Unspoken History, BBC Four

The Secret Life of Rubbish / The Toilet: An Unspoken History, BBC Four

The history, and complexity, of getting rid of things

Is scatophilia on the loose at the BBC? After The Secret Life of Rubbish, billed as "a view of the history of modern Britain - from the back end where the rubbish comes out", creatively programmed with a repeat of The Toilet: An Unspoken History on the same night, you might be forgiven for thinking so. Both reach, so to speak, the parts that most other television documentaries don’t.

I’ll leave the toilet, or rather its energetic presenter Ifor ap Glyn (pictured by a privy, below right), to speak for himself. Ap Glyn covers familiar and not-so-familiar historical ground, from Thomas Crapper to the architectural glories of Victorian public conveniences, from ancient Rome to a comedy night celebrating the lavatorial. Who would have thought there was so much international mileage here? From the delicate add-ons of Japanese sanitation (heated seats and direct-from-the-pan washing facilities), through to challenges being met in Bangladesh where communities are being taught to stop shitting by the roadside through innovations that promise great improvements on the sanitary, if not the especially aesthetic front. There’s even an international conference on the subject, which ap Glyn caught in China. But the toilet seems to be telling an essentially one-directional narrative, where progress continues – the way down being, essentially, on the way up. Once it’s down the dunny, as long as we don’t have to wade around in the stuff, it's out of sight, out of mind.

Rubbish is somehow, well, more multivalent, and director Chris Durlacher’s two-parter The Secret Life of Rubbish restricts itself to our own not-so-sceptred isle from World War Two through to the end of the Eighties. It’s a period that catches the contrasts of a society moving from thrift to consumption, and until more recently not much concerned whether, as long as it’s not in our own back yard, the rubbish goes up in smoke, or into someone else’s back yard (in the case of Packington Hall, one of the country’s largest landfill locations, a very aristo one). But its lingo has words like "waste" and "salvage" that have almost biblical associations, so there’s more at stake than meets the eye.

Rubbish is somehow, well, more multivalent, and director Chris Durlacher’s two-parter The Secret Life of Rubbish restricts itself to our own not-so-sceptred isle from World War Two through to the end of the Eighties. It’s a period that catches the contrasts of a society moving from thrift to consumption, and until more recently not much concerned whether, as long as it’s not in our own back yard, the rubbish goes up in smoke, or into someone else’s back yard (in the case of Packington Hall, one of the country’s largest landfill locations, a very aristo one). But its lingo has words like "waste" and "salvage" that have almost biblical associations, so there’s more at stake than meets the eye.

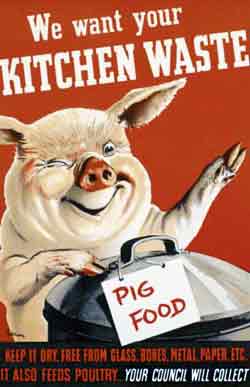

Secret Life… manages a number of omissions: not a mention of that pioneer on the subject, Charles Dickens (though his golden dustman assumed a new meaning when the Thatcherite Eighties brought privatisation). It’s (thankfully?) light on Marxist history, though we get Scottish philosopher John Scanlan, whose On Garbage has been credited as “the first book to examine the detritus of Western culture in full range”, as one of the relatively few talking heads. The real hero here is archive, from news clips and period interviews through to fascinating public information material, posters and cartoons included (the mere existence of archives presupposing a non-throwaway approach). The lack of a credited narrator heightens the sense that we're watching public service stuff.

We don’t even seem to get a credited narrator, which heightens the sense that we're watching public service stuff

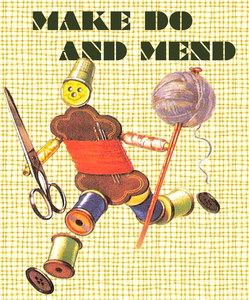

Wartime privation and post-war rationing meant that a use had to be found for everything – the philosophy of “make do and mend”. The notion of “mobilise your scrap” found bones becoming glycerine used for bombs raining down on the Nazi enemy. What you just had to throw away went into the “pig bins” – “how you’ll all save your bacon” (pictured below right). Birmingham was ahead of the national game, with a philosophy of waste that ended up with almost zero throw-away, and dustmen picking potential recycle material off the conveyor belt for overtime – the rest was burnt in Enronic “destructors”.

Then, predictably from across the pond, came a lifestyle of the new, and the appeals of consumption (including, at its most blatant, planned obsolescence). The metal dustbin was followed by the plastic bag, and eventually the wheely bin – the increasing ease of each brought increased volumes of waste. Birmingham became proud of the Bullring, where shopping for the new meant more dumps for the old, the "wastelands of abundance”. It took the dustmen's strike of early 1979, when Leicester Square in London was filled almost to overflowing, to remind us of the consequences – though earlier scares, like the (then completely legal) dumping of drums of cyanide outside Nuneaton in 1972, played their part.

Then, predictably from across the pond, came a lifestyle of the new, and the appeals of consumption (including, at its most blatant, planned obsolescence). The metal dustbin was followed by the plastic bag, and eventually the wheely bin – the increasing ease of each brought increased volumes of waste. Birmingham became proud of the Bullring, where shopping for the new meant more dumps for the old, the "wastelands of abundance”. It took the dustmen's strike of early 1979, when Leicester Square in London was filled almost to overflowing, to remind us of the consequences – though earlier scares, like the (then completely legal) dumping of drums of cyanide outside Nuneaton in 1972, played their part.

There are a few happier stories, such as the first bottle bank, set up in Barnsley in 1977, proving that money could be made through recycling. “Cash from trash” had its own laws. Perhaps the saddest speaker here was longtime waste scientist John Barton, still going strong at Leeds University’s Solid Waste Management Group, who established a pioneering recycling factory outside Doncaster. It lost the war on waste to landfill, because it ran at a loss of around three per cent on turnover, despite virtually nothing being thrown away.

Whether there’s a moral imperative to waste management is a question that’s probably come to the fore only after Durlacher’s cut-off point, though the tone of a BBC presenter in a clip from 1960 sounds distinctly censorious when he empties a bin with all of two days' worth of throw-away. It seems to ask - should we be doing better?

In short, is it in human nature to discard wantonly, or do we derive pleasure from ordered re-use? We get some vintage human faces to illustrate the old days: from 90-year-old dustman Ernie Sharp (the first of many who remind us, if we needed to be, of the dignity of the job; one of them even enjoys a spot of rubbish collecting on his overseas hols), to the lovely Eileen Mead, who's snipping away in “make do and mend” mode (pictured above left) today as if the country's survival still depended on it. At one point, she was challenged to “find a use” for even the smallest piece of discard cloth - if only we'd seen what she came up with. If she's one of the saints of rubbish, you could find their fictional opposite numbers, the Cavalier sinners of throw-away, in the likes of the period's Mr Creosote, John Self or Viz magazine. So it's little surprise that no one steps up here to admit to just loving creating a bit of mess. Perhaps, as with Ifor ap Glyn's beloved toilets, we all do it - just we never talk about it.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

theartsdesk Q&A: director Stefano Sollima on the relevance of true crime story 'The Monster of Florence'

The director of hit TV series 'Gomorrah' examines another dark dimension of Italian culture

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Monster of Florence, Netflix review - dramatisation of notorious Italian serial killer mystery

Director Stefano Sollima's four-parter makes gruelling viewing

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Diplomat, Season 3, Netflix review - Ambassador Kate Wyler becomes America's Second Lady

Soapy transatlantic political drama keeps the Special Relationship alive

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

The Perfect Neighbor, Netflix review - Florida found-footage documentary is a harrowing watch

Sundance winner chronicles a death that should have been prevented

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Murder Before Evensong, Acorn TV review - death comes to the picturesque village of Champton

The Rev Richard Coles's sleuthing cleric hits the screen

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

Comments

I've tried those Japanese

Secret life of rubbish was

but what was it that Eileen