The Chaser Years, Maverik Gallery, London | reviews, news & interviews

The Chaser Years, Maverik Gallery, London

The Chaser Years, Maverik Gallery, London

Catch this brief but extraordinary show of music photographer Peter Williams

“Hot sweaty tight jammed in can’t breathe heart pumping centre of the universe Monday night action in town. Racing down to Bar Rumba at midnight through the blaring siren wailing darkness of south London to the tinsel town wet streeted fakeness of the West End and the That’s How it Is sessions, Gilles Peterson, James Lavelle, UFO, Patrick Forge, Roni Size spin…” [sic] Peter Williams, London, 1994.

That was written by the photographer whose 70 black-and-white photographs are showing at a blink-and-you-miss-it gallery in east London until Saturday. Since the heyday of London’s New Jazz scene in the 1980s and Nineties, his work has become an archivist’s treasure trove, preserving that too often overlooked strand of British music history. And as the above reveals, Williams is also something of a jazz poet - inspired, he says, by Hunter S Thompson and The Last Poets.

Almost as important as the photographs, Williams’s captions illuminate the thrill of clubs like the dark, moody dive La Prison in Stoke Newington where Courtney Pine practised his Coltrane riffs in 1988, and the West End’s Bar Rumba where Gilles Peterson introduced his eclectic tastes to his generation of jazz lovers and the new jazz dancers.

For Williams, the joy of photographing the icons of bebop and American jazz (Yusef Lateef, Herbie Hancock, Don Cherry) alongside new young British faces (Courtney Pine, Andy Sheppard, IDJ [I Dance Jazz] Jerry, Roni Size, Soweto Kinch) was matched by the way his photographs were used in the magazine Straight No Chaser, mouthpiece for the new scene.

For Williams, the joy of photographing the icons of bebop and American jazz (Yusef Lateef, Herbie Hancock, Don Cherry) alongside new young British faces (Courtney Pine, Andy Sheppard, IDJ [I Dance Jazz] Jerry, Roni Size, Soweto Kinch) was matched by the way his photographs were used in the magazine Straight No Chaser, mouthpiece for the new scene.

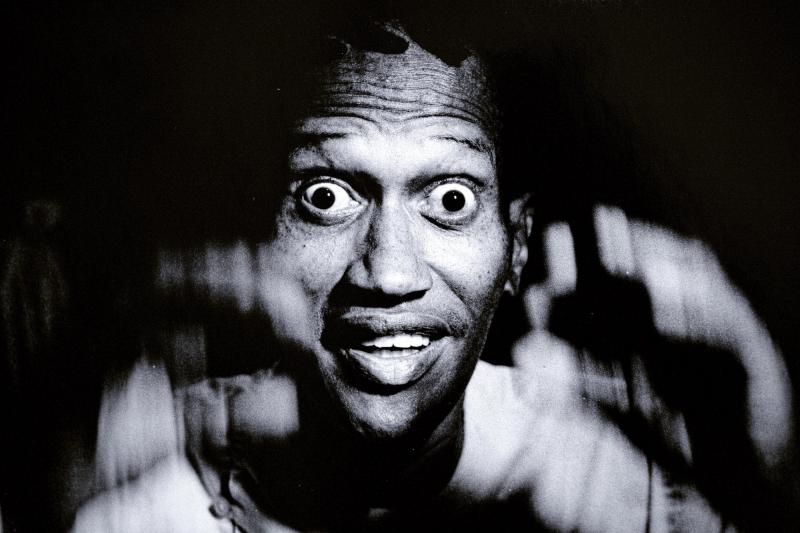

Williams on IDJ Jerry, London 1988 (pictured right): “My first Straight No Chaser shoot, and I used the Baroque elegance of the ex-Yugoslavian embassy to capture the extraordinary jazz dancer with IDJ Jerry exploding energy, uncontainable brilliance, the space becomes a theatre... Jerry spirals over a checked marble floor.”

Paul Bradshaw, the magazine's publisher and editor, created a wall of covers and inside spreads and explains, “Hanging them in a gallery alongside Peter’s photographs illustrates how they were employed in a graphic context.” Chaser was many times awarded for its radical originality in the pre-digital era and its influence on many young artists who understood the connection between the music and the images.

The exhibition is a showcase for Williams's recent prints of the originals used in the magazine, and it separates them away from the thrilling cacophony of layouts with custom-made jazzy hip-hoppy typography and audaciously colourful overprinted pages – the magazine’s identity – and into the world of white-walled galleries where they now belong, and work as preservers of historical moments.

“I had had a furious argument with Herbie over a soundcheck photo misunderstanding and he didn’t know that I was taking the record label portrait of him next day." Williams on Herbie Hancock, London 1994 (pictured below). "In his hotel room, he shouted, 'Oh, man, it’s you!' I said, 'Yes.' We got talking about the music he wrote for Antonioni’s film Blow Up. Pretty soon he was laughing.”

All around the gallery, we are reminded of how the images were originally used but, at the same time, can relish their quality in isolation from the text. Williams’s background at the Royal College of Art influenced his approach to photography, especially printing. Strictly a dark-room, non-digital man, he uses a 19th-century silver gelatin process: “Wonderfully intuitive,” he describes it. “No print ever looks the same.”

All around the gallery, we are reminded of how the images were originally used but, at the same time, can relish their quality in isolation from the text. Williams’s background at the Royal College of Art influenced his approach to photography, especially printing. Strictly a dark-room, non-digital man, he uses a 19th-century silver gelatin process: “Wonderfully intuitive,” he describes it. “No print ever looks the same.”

He frames each one himself using beautifully treated oak. His personal style operates at all levels, introducing extremes of blackness and contrast as well as exploiting his liking for graininess and blur.

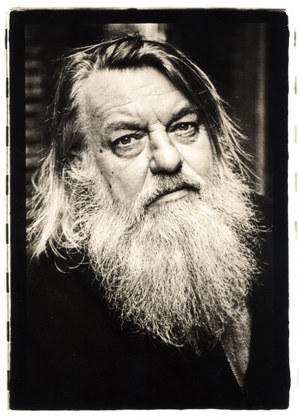

Another feature is the musicality in some portraits – most obviously in his collaboration with the balletic jazz dancer Jerry. For Robert Wyatt (pictured right), he took an entirely different approach, transforming him into a grand but modest 19th-century philosopher, which of course, perfectly captures his spirit.

Another feature is the musicality in some portraits – most obviously in his collaboration with the balletic jazz dancer Jerry. For Robert Wyatt (pictured right), he took an entirely different approach, transforming him into a grand but modest 19th-century philosopher, which of course, perfectly captures his spirit.

As the exhibition was being planned, Jamie Cullum sent the world a message on his blog for Radio 2. He titled it "Straight No Chaser", and paid homage to the late magazine and to Williams’s photographs. Reminiscing about his teen years in Chippenham, he wrote, “It was early on in my world of jazz appreciation.” He describes his passion for NME, Melody Maker, “and one called Straight No Chaser… unlike any other. The magazine shone out at me, printed on gorgeous paper, the front cover proclaimed to have an article about Sun Ra inside. I picked it up and devoured the article about the outerspace jazz planeteer…”

Cullum described Peter Williams’s contributions as “giving the new vibrant world of jazz a fresh image with a strong link to the past. In keeping with the magazine's philosophy of presenting jazz like the club scene it always belonged to.” And he closed with a plug: “There's an exhibition of Pete's work at the Maverik Showroom in London. Check it out and dig out an old copy of Straight No Chaser. It still feels like the future.”

Cullum described Peter Williams’s contributions as “giving the new vibrant world of jazz a fresh image with a strong link to the past. In keeping with the magazine's philosophy of presenting jazz like the club scene it always belonged to.” And he closed with a plug: “There's an exhibition of Pete's work at the Maverik Showroom in London. Check it out and dig out an old copy of Straight No Chaser. It still feels like the future.”

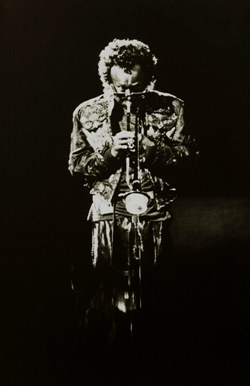

Williams on Miles Davis, London 1989 (pictured left): “An early job for the magazine, I arrived late and a young, nervous stage manager asked me to stand in the wings as it was pandemonium down at the front. I watched Miles walk on stage and start playing… I had little knowledge of his stage choreography in that he would often perform with his back or profile to the audience. He spent the entire gig in profile, staring straight into the wings where I stood. Phenomenal luck.”

- Peter Williams Photography, Maverik Showroom, until Saturday 20 November

- See Peter Williams's website

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Comments

...