Generation Jihad, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

Generation Jihad, BBC Two

Generation Jihad, BBC Two

Important series on the enemy within

For a number of years I used to live opposite Abu Hamza. You didn’t see him much. I remember a Mercedes spilling devoutly robed football fans who had come to watch the game round his place when Iran played the USA in the 1998 World Cup. After 9/11, the street would occasionally fill with swooping fleets of police vehicles. Once they decanted a squad of space-suited forensics looking, presumably, for incendiary devices.

Britain has a bit of history in the business of nurturing revolutionaries. The author of the Communist Manifesto is famously buried in Highgate. There’s a blue plaque in King’s Cross bearing the name of Lenin. Among Joseph Conrad’s shady cadre of continental agitators in The Secret Agent, the means of imposing their will was also the bomb. But they look positively cosy compared to the radicals under consideration in Peter Taylor’s new series. Watching Generation Jihad made you almost nostalgic for the good old days of mutually assured destruction, when there was a final guarantee against apocalypse: the ideological enemy was just as terrified of death.

This series on the radicalising of a small portion of Britain’s Muslim youth needed to be made, and it needed to be made by Taylor, who has been behind definitive films on Northern Ireland and, three years ago, Age of Terror. Most relevantly in the circumstances, in 1988 he reported from the streets of West Yorkshire on the incandescent reaction to The Satanic Verses and the catalystic fatwa. It was this event, it was explained, which prompted many British Pakistanis to re-examine their faith and promote religion above ethnic identity.

More than two decades on, Taylor returned to the county's post-industrial towns with their enclosing hills and broad steeples to meet two men who have run up against Britain’s stringent anti-terror laws. Jihadis don’t regularly give interviews to the BBC, but then neither of these were proved to be terrorists. Born and bred in Halifax, both have served two years in prison not for plotting terrorist acts but for harbouring material that could be seen to support it. One is the first person to be sentenced in this country for glorifying terrorism. “I don’t think I’m going to be the last,” he said. The police noted his lack of shock on being arrested. “Why would I look shocked?” he said. “This is happening all the time.”

Not all the time. But this was the final point of the first episode: that the effort to nip terrorism in the bud is being so forcefully pursued that it will inevitably have the counterproductive effect of seeding more radicals. Needless to say, Taylor's two interviewees came across as ordinary, even personable young men who made the expected arguments about Palestine, Afghanistan and Iraq. “As Muslims we don't have loyalties to wherever we’ve been born and bred,” explained one. “We have loyalties to Islam and the Muslims and that’s where our priorities now lie.” When one of them came home from prison, for three months there was a stream of gift-bearing well-wishers, evidently unconvinced of his jihadist ambitions. “He couldn’t kill a fly,” said a proud father. “He’s not a terrorist, he’s my son.”

Taylor explained that there need to be more jigsaw pieces in place for a radical to turn terrorist: disaffection converts to murderous intent when radical imams are allowed to fill a space vacated by parents. For disaffected young white men, argued one Muslim youth worker who knew one of the 7/7 bombers, it might be the National Front. For young black men it’s gang wars and knife crime. For the disaffected young Muslim, the replacement family is the local jihad soc preaching seductive certainties about a literal interpretation of Islam and a khalifat under sharia law uniting a worldwide Islamic state.

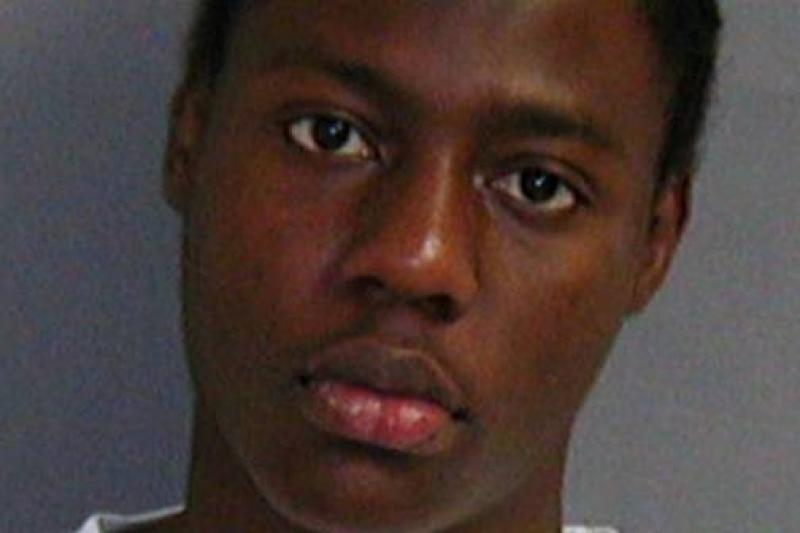

For both the underpants bomber Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, who spent three years at UCL, and Germaine Lindsay, one of the 7/7 terrorists, this was precisely the siren wail they answered. The youth worker who had Lindsay under his wing for a couple of years was satisfied that he had done all he could to help him. But a “bizarre cult that you’ve got to follow the societal cultural protocols of a sixth century Arabia” had proved more seductive. Generation Jihad’s success as a piece of psychological profiling can only be judged at the end of its run. It is produced and directed by Fatima Salaria.

- Generation Jihad continues next Monday on BBC Two.

- Watch part one on BBC iPlayer.

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

Black Rabbit, Netflix review - grime and punishment in New York City

Jude Law and Jason Bateman tread the thin line between love and hate

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

The Hack, ITV review - plodding anatomy of twin UK scandals

Jack Thorne's skill can't disguise the bagginess of his double-headed material

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Comments

...