John Martin: Apocalypse, Tate Britain | reviews, news & interviews

John Martin: Apocalypse, Tate Britain

John Martin: Apocalypse, Tate Britain

An apocalyptic visionary is brought out of storage, at last

John Martin is heaven. Well, as many of his contemporaries would have pointed out, John Martin is also hell, or The Last Judgement, or, as the Tate’s show title would have it, the Apocalypse at the very least. For John Martin was, after Turner, the 19th century’s premier painter of catastrophe. Unlike Turner, however, he was not much rated by the more respected critics, and his work, frequently oversized, tends to spend more time in storage than on the walls of public galleries.

The “of his day” is important, for Martin was, I agree with the Victorians this far, not the world’s best painter. He was pretty good – very good sometimes – but it is the ideas he was interested in, how he created his work, and what his work represents to us today that is the story.

John Martin was, first of all, not a Victorian at all. Born in 1789, under George III, there were two more kings to go before Victoria came to the throne when Martin was already nearly 50. This matters not merely as a pedantic point, but to understand his vision: Martin grew up when the Romantics were sweeping all before them, and much of his vision is that of a Romantic.

Born in Northumberland to an artisan father who was more frequently out of work than in it, Martin was briefly apprenticed to a coach painter in Newcastle, but he soon moved over to work for a drawing master, arriving in London as a china and glass painter (one of the two known examples of his china painting that has survived is on exhibition here). He made his living also by painting charming little views and scenes in a typically Regency style, with neat, manicured landscapes showcasing neat, manicured people (Kensington Gardens, 1815, pictured right). They are delightful, and most unexpected for those who only know his later work, and it is good to see them here. They showcase the new world of commercial leisure that Martin so astutely tapped into.

Born in Northumberland to an artisan father who was more frequently out of work than in it, Martin was briefly apprenticed to a coach painter in Newcastle, but he soon moved over to work for a drawing master, arriving in London as a china and glass painter (one of the two known examples of his china painting that has survived is on exhibition here). He made his living also by painting charming little views and scenes in a typically Regency style, with neat, manicured landscapes showcasing neat, manicured people (Kensington Gardens, 1815, pictured right). They are delightful, and most unexpected for those who only know his later work, and it is good to see them here. They showcase the new world of commercial leisure that Martin so astutely tapped into.

For once he started painting his grand apocalyptic visions, aiming to startle at exhibitions, the etchings and mezzotints that were created were then reproduced, in magazines, in books, and were themselves displayed in printshops and even schools. Martin was one of the earliest artists to rely on mechanical means of reproductions, and the Industrial Revolution’s new world of trains, newspapers, books and commerce, to promote and sell his work.

Martin's tidy, Jane Austen-like world of Kensington Gardens (notably, the year Emma was published, dedicated to the Prince Regent at his own request) soon gave way to the biblical or mythological scenes of destructive grandeur for which he is now known. Yet some of the Regency tidiness always remained: Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still Upon Gibeon (1816) shows the cracking sky as the sun screeches to a halt, but Joshua (flashing a very nice pair of legs in quasi-Roman get-up) could, with more clothes on, have been one of Kensington Garden’s neat little pedestrians, while the armies he commands are tin-soldier tidy, complete with romping, prancing white charger.

The more famous Belshazzar’s Feast (1820, and then several later versions) has hissing snake statuary, dazed and terrified crowds, a reddish-orange doom and a violent right-leaning composition to indicate terror. It also has a nicely set table on which the plate and fruit shines brightly (nothing is even knocked over, despite sprawling bodies abounding).

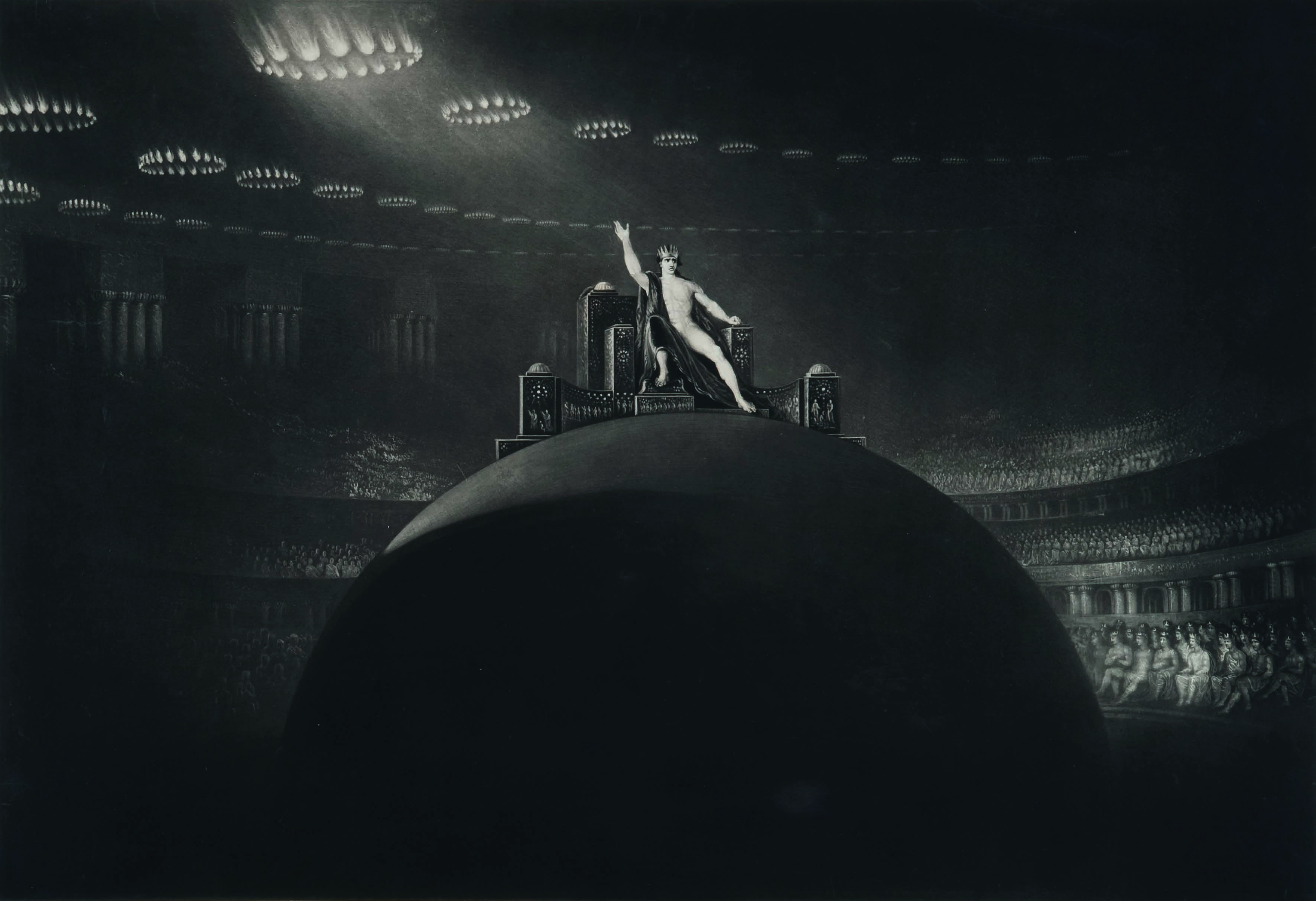

By the mid 1820s, Martin was making a speciality of mezzotints, a form of reproduction via an inked plate which gives a velvety deep-black background. In this he excelled, first finding fame (and fortune) with his illustrations to Milton’s Paradise Lost (Satan in Council, 1831, pictured left). The scraped-out white areas whirl in vortexes around the mezzotints darkness, suiting both the dreams of grandeur of the artist, as well as the poem’s great subject. These were followed by a series of prints of Bible subjects, which made Martin famous across the country and beyond, taking his prints into homes, shops and Sunday schools everywhere.

By the mid 1820s, Martin was making a speciality of mezzotints, a form of reproduction via an inked plate which gives a velvety deep-black background. In this he excelled, first finding fame (and fortune) with his illustrations to Milton’s Paradise Lost (Satan in Council, 1831, pictured left). The scraped-out white areas whirl in vortexes around the mezzotints darkness, suiting both the dreams of grandeur of the artist, as well as the poem’s great subject. These were followed by a series of prints of Bible subjects, which made Martin famous across the country and beyond, taking his prints into homes, shops and Sunday schools everywhere.

His paintings, too, were not confined to the homes of the rich and the Royal Academy. He used travelling exhibitions, often set up in luxury shopping districts, in London and in the new industrial cities, where paying customers queued to see his visions, and read his interpretations in handbooks specially printed: The Deluge, The Fall of Nineveh, The Fall of Babylon – all these subjects precisely met with the taste of the emerging middle classes, now with a little cash in hand as the Industrial Revolution brought entertainment to the masses.

Pandaemonium and The Celestial City and River of Bliss (both 1841), once more illustrating Paradise Lost, were Martin’s calling cards when they were exhibited at the Royal Academy, one fiery red, showing the destruction of a range of buildings that were clearly, to Londoners’ eyes, based on the great Adelphi terrace beside Waterloo Bridge, as well as prefiguring the new Houses of Parliament that were currently being built a little further down the river. The frame, designed by Martin too, has dragons and snakes curling around its borders: the monsters are seeping out of the river and into our world.

If the masses loved it, could it be art, worried the critics?

This escape of horrors into our world is the key to the picture. Martin was deeply involved with a subject that was close to every Londoner’s heart, the problem of sewage disposal. Today it sounds comic, and a bit odd, but as the city grew ever larger, and more and more effluent was dumped daily into the river, this was no trivial subject. Martin even produced his own plan for an intercepting sewer. (It was seriously considered, but the political will to cleanse the great sewer that was the river was not found for nearly two decades more, after a summer that was so hot the water of the Thames actually fermented.) No one at the Royal Academy would have missed the reference to that stinking horror, however, which would have made the sweet pinky-blues of The Celestial City next to it all the more desirable.

Martin’s final work was the great triptych of The Last Judgement (1845-53). Once more he exhibited the paintings in London, and then toured them across the country and even, after his death, to New York and Australia. As with so much of Martin’s work, however, the canvases were derided by the art world. (Ruskin dismissed Martin as commerce rather than art, although his sneering reference to him as a “workman” does suggest that class condescension came into the equation too.)

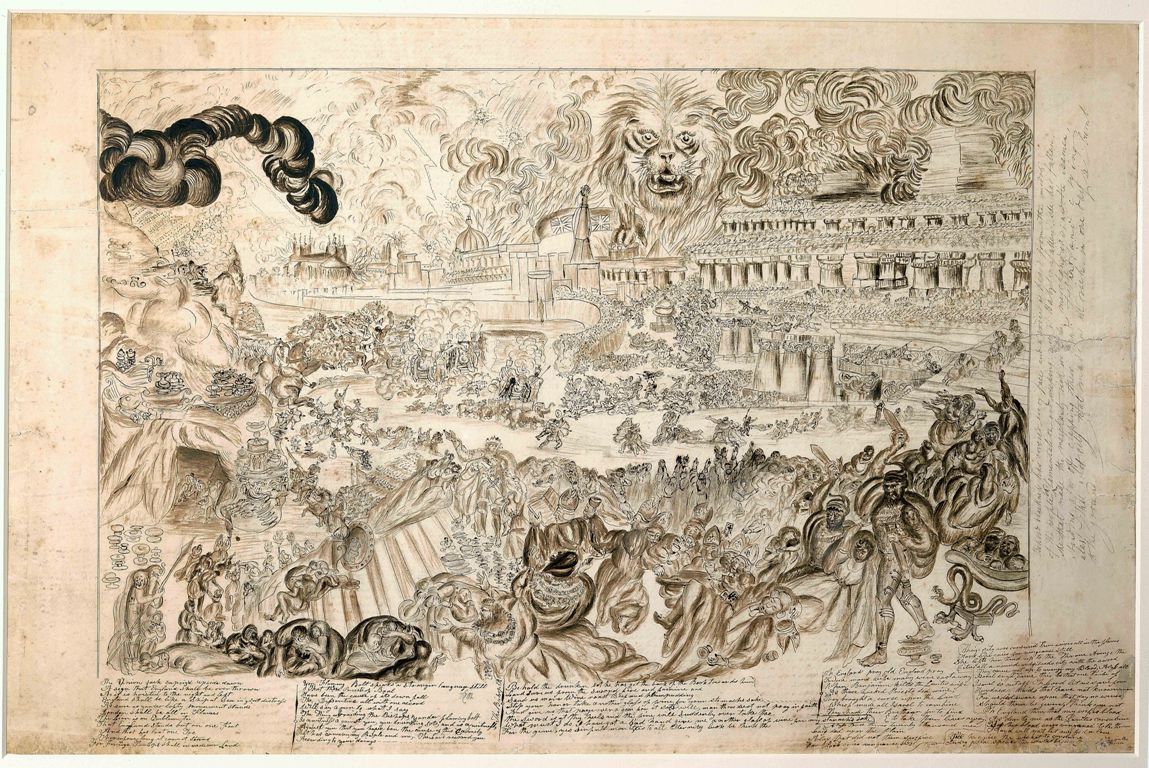

Part of the problem was precisely the success and popular acclaim: if the masses loved it, could it be art, worried the art world? And here, for the first time, we see the split between “high” and “low” appearing, the idea that if an art form was popular, it couldn’t actually be any good. Others merely suggested anyone that preoccupied with apocalyptic drama must be insane. This was fed by the fate of his brother Jonathan, who truly was insane, and whose legal defence Martin paid for after Jonathan attempted to burn down York Cathedral. (He ended up in Bedlam.) London's Overthrow (pictured left, by Jonathan Martin) included elements from many of his more famous and saner brother's work.

Part of the problem was precisely the success and popular acclaim: if the masses loved it, could it be art, worried the art world? And here, for the first time, we see the split between “high” and “low” appearing, the idea that if an art form was popular, it couldn’t actually be any good. Others merely suggested anyone that preoccupied with apocalyptic drama must be insane. This was fed by the fate of his brother Jonathan, who truly was insane, and whose legal defence Martin paid for after Jonathan attempted to burn down York Cathedral. (He ended up in Bedlam.) London's Overthrow (pictured left, by Jonathan Martin) included elements from many of his more famous and saner brother's work.

But the "Mad Martin" persona is a red herring. Despite the chaos of the subjects, Martin's work is always very measured, very balanced. For proof of that, the Tate has on display at the very end the contemporary artist Glenn Brown’s take on The Last Judgement, The Tragic Conversion of Salvador Dalì (1998). Brown has turned the work on its side, reproduced it in garish DayGlo pigments, and made a pig’s ear out of an original that was, if not a silk purse, certainly a nicely embroidered one. Brown’s work resembles nothing so much as one of those 1960s album covers of the sub-Jesus Christ Superstar school. It makes you realise what a good, solid painter Martin really was.

Click on the images to enlarge

[bg|/ART/Judith_Flanders/JonMartin]

- Alpheus and Arethusa, 1832 (Private Collection)

- The Eve of the Deluge, 1840 (The Royal Collection © 2010 Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

- The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, 1852 (Laing Art Gallery Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums)

- Kensington Gardens, A View of the Serpentine, 1815 (Yale Centre for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection)

- The Bard, 1817 (Laing Art Gallery, Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums)

- The Destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, mezzotint, 1832, (Michael J Campbell)

- John Martin: Apocalypse at Tate Britain until 15 January, 2012

Buy

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Comments

Tate appears to have thought