theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Christopher Eccleston | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Christopher Eccleston

theartsdesk Q&A: Actor Christopher Eccleston

Straight-talking star of The Shadow Line explains why there's no black and white

Christopher Eccleston’s performances have a raw-boned, visceral quality which makes him a sometimes unsettling - but always compelling - actor to watch.

However, his best work has undoubtedly been reserved for the small screen. He is, of course, known to millions as the ninth Doctor Who, successfully ditching the somewhat fey posturings of previous incumbents for an altogether more earthy – or should that be earthly? – and contemporary interpretation of the Time Lord. But it is in classic television dramas such as Cracker (1993-4), Hillsborough (1996), Our Friends in the North (1996) and Clocking Off (2000) that he truly shines, slipping with unnerving ease under the skin of his characters. (Pictured below: Eccleston with Kate Winslet in Jude.)

Recently, on a beautiful spring day, I met up with Eccleston in a north-London park to talk about, among other things, The Shadow Line, a new seven-part series created by Hugo Blick for BBC Two, which in addition to Eccleston stars Chiwetel Ejiofor, Stephen Rea and Lesley Sharp. It's no secret that some journalists consider Eccleston to be somewhat prickly. He is indeed very direct but only, I suspect, because he has a very strong attachment to the truth, which is clearly reflected in his work.

Recently, on a beautiful spring day, I met up with Eccleston in a north-London park to talk about, among other things, The Shadow Line, a new seven-part series created by Hugo Blick for BBC Two, which in addition to Eccleston stars Chiwetel Ejiofor, Stephen Rea and Lesley Sharp. It's no secret that some journalists consider Eccleston to be somewhat prickly. He is indeed very direct but only, I suspect, because he has a very strong attachment to the truth, which is clearly reflected in his work.

HILARY WHITNEY: You always like to make it very clear that you are from Salford, not Manchester. What exactly is the difference?

CHRISTOPHER ECCLESTON: Salford existed first. Salt Ford. Manchester came afterwards. Actually, I only lived in Salford until I was seven months old and then we moved to Little Hulton, which is only eight miles away but it felt like quite a distance then. I was always going back to see my grandparents and I was constantly reminded that I was from Salford. There was – still is - a very distinct culture in Salford. It’s quite a tough place, but people from Salford are very proud and have a very self-deprecating sense of humour. There’s an expression, “You can always tell a Salford lad but you can’t tell him anything”. But I was brought up on a council estate in Little Hulton where I lived until I was 19.

Tell me a bit about your upbringing.

My old man was a stacker truck driver at Colgate Palmolive for about 20 to 30 years and then a warehouse foreman. That’s where my mum and dad met – she worked on the floor above him on the TA, that’s the toilet articles floor. She came down in the lift one day and when the lift doors opened, there was my dad, sat on the stacker truck. And I’ve got twin brothers, Keith and Alan, who are eight years older than me.

So where did the ambition to become an actor come from?

Well, I couldn’t do anything else. I was quite good at sport but not quite good enough. I was very fit and I was very committed but I didn’t have the talent to be the footballer I wanted to be. Both my brothers are really good with their hands and did apprenticeships - Alan was an upholsterer, his furniture is beautiful, and Keith was a woodworker and shopfitter - but I’m useless at anything like that, I can’t even change a light bulb, so I was really at a loss. I didn’t do very well at school and I had to go to a sixth form college to resit my O levels. Sixth form college was very different to school, a much more – well, middle-class environment, I suppose. There wasn’t so much aggression and pressure not to conform and I did this play.

Out of the blue? Had you ever thought about acting before?

You know, looking back I realise I was always doing Jimmy Cagney impersonations as a kid. I remember trying to dance like Gene Kelly on the oilcloth in the kitchen and when we went to see the first Three Musketeers film - the Richard Lester one, which I think is fantastic – I remember nicking my mum’s umbrella and sword fighting all the way home, so I think I was always performing in a way. And my position in the family made me quite a watcher, because there were two pairs, you know, mum and dad and then Alan and Keith, and then there was me, the youngest by eight years, and that kind of gap makes you very watchful.

So you grabbed the opportunity to be in a play?

It was more that there was a girl in it that I fell in love with. It was called Lock up Your Daughters and it was a slightly off-colour musical adapted from a novel [Rape Upon Rape] by Henry Fielding. Anyway, I met a woman in it so I thought, this is the life for me, but then I finished college and spent six months working in a warehouse, lost again, until my mother heard about a two-year drama course at Salford College of Technology. I auditioned and got in.

Salford Tech was based in the Adelphi Building and when I got home at the end of the first day and told my mum she said, “Well, when I was 14,” – both my mum and dad started work when they were 14 – “my first ever job was to take a message to that building.” So every morning when I walked up those stairs, I would imagine my 14-year-old mother, going up those stairs. Fourteen! I mean, it’s nothing, is it?

Did you feel self-conscious telling your mates that you were doing drama?

No, I think that’s a huge cliché about the North which was kind of furthered by films like Billy Elliot.

I was thinking more about how self-conscious people are at that age.

OK, yeah. I see what you mean. But no, I wasn’t self-conscious at that age. I mean, I was self-conscious, but not about that. Besides, I think everyone around me kind of went, “Oh, he wants to be an actor, that makes sense,” because I was always taking the mickey and looning about, doing impersonations. So I started to learn all about Stanislavski and Brecht and all that, which I found quite intimidating. It seemed very intellectual and in an odd way that made me more introverted because I became under the misapprehension that acting is an intellectual pursuit and it’s not - it’s an instinctive, emotional pursuit which requires a certain amount of reading, but the most interesting actors are the ones who act from their gut. But I didn’t realise that for many years.

I think it’s often a shock, when you’re young and interested in drama, to suddenly find yourself bombarded by all these different theories – many of which can seem quite abstract.

Yes, I agree, although I think I tapped into a bit of an evangelical aspect which appealed to me. Peter Brook’s Empty Space was very important to me because he talked about rough theatre, which is basically that all you need is an empty space, a person walking through it and a person to watch it. Of course, the theatre that I had, not gone to see, because I hadn’t really been to see any, but been aware of, was very bourgeois and very pros arch. All that Noel Coward stuff - neutered theatre. But Brook and Brecht and Stanislavski had this kind of evangelical, almost religious quality and I could find a way in with that. Anton Artaud also had a big affect on me - Theatre and Its Double. I didn’t understand it but I thought it was very compelling.

At the same time I was doing English A level. I was taught by a very good teacher called Sorah – B Sorah, I don’t know her first name, we didn’t know their first names in those days - and she taught the First World War poets, which had a massive impact on me, particularly Sassoon’s journey of conscience. At the beginning of the First World War [Siegfried] Sassoon was writing poems saying that it was good and noble and natural to spill your blood for the mother nation and within a year he was saying “I apologise, this is vile.” He went through a number of stages and this journey of an artist’s conscience was fascinating to me, because he admitted he was wrong through art. (Pictured left: Eccleston in The Others, 2001.)

At the same time I was doing English A level. I was taught by a very good teacher called Sorah – B Sorah, I don’t know her first name, we didn’t know their first names in those days - and she taught the First World War poets, which had a massive impact on me, particularly Sassoon’s journey of conscience. At the beginning of the First World War [Siegfried] Sassoon was writing poems saying that it was good and noble and natural to spill your blood for the mother nation and within a year he was saying “I apologise, this is vile.” He went through a number of stages and this journey of an artist’s conscience was fascinating to me, because he admitted he was wrong through art. (Pictured left: Eccleston in The Others, 2001.)

There was that series of unbalanced poems – well, they’re not unbalanced in a way, they’re quite rational in their irrationality, such as Blighters. Sassoon came back on leave from the Front, obviously suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, and went into the West End to see a review about the war which probably had something along the lines of “We’re Going to Hang Out Our Washing on the Siegfried Line” in it and went home and wrote this six – eight? – line poem about the harlots on the stage, imagining Panzer tanks smashing through the back of the theatre and rolling over the audience because he was so repulsed at how detached people were from the reality of war and that art was misrepresenting it. That had a massive impact on me, as did Isaac Rosenburg’s poem Break of Day in the Trenches, and [Robert] Graves’s poetry, and somehow, all this came together and shifted my idea of what poetry and theatre was. Until then I had thought of poetry and theatre how I perceive opera and ballet today - very rarified – and then I realised they could be weapons, which is very appealing to a 19 year old.

I also started looking a bit more closely at my northern heritage - seeing Kes and Albert Finney [also from Salford] in Saturday Night, Sunday Morning; Ken Loach films and Play for Today – all very writer-led. And that was the third thing, really. I’d been a remedial reader at school and when I went to Salford Tech and finally got a good teacher, reading just opened up for me and I read avidly. So when we were taught, on my drama course at Salford Tech, that the writer was the most important person [in drama] it made complete sense to me. And that’s what British television needs to readdress, because without writers, we don’t go to work. So those three things: the poets, the likes of Brecht and Artaud and appreciating writers – that’s what really set me off.

Do you think writers are still appreciated in the same way? I was talking to a writer recently, who has given up on television because it’s just too frustrating – writers are constantly being asked to rewrite scripts which are eventually rejected by someone way up the food chain.

They [TV executives] don’t want originality – I think it’s a kind of unconscious disapproval of creative people. “I can’t do it so I’m going to stop you doing it. Don’t make me feel stupid by surprising me.” Years ago producers would say to writers, “What are you thinking about, what do you want to write about?” Since then, we’ve gone through a period where producers were going, “This is what we want you to write about.” That’s not creative. Writers have to be obsessed with things – that's how writers like [Dennis] Potter and [Alan] Bleasdale were able to write such brilliant scripts. It’s kind of a respect for the creative process. I don’t mean to rarify writers or treat them like gods or priests, but it’s not a prescriptive process. You cannot write a script by committee. It’s just not possible. All you will get is pap.

But having said all that, actually things do seem to be changing – look at the BBC at the moment. Look at The Shadow Line and The Crimson Petal and the White; they seem to be giving writers a bit of space and putting them at the centre of the work again.

I think Bleasdale famously took Jimmy [McGovern] out for a pint early on and said, “You know, keep your mouth shut,” – because Jimmy’s very opinionated, as he should be – but what Bleasdale was saying was, if you shout your mouth off too much then you won’t be able to do the thing which you love, which is writing. Do the shouting via your writing. He was telling him to be careful politically, to be careful not to piss people off. Not that Jimmy is, thank God. I can’t stand people who are careful about pissing people off.

So that was the motivation behind going to drama school?

Yeah, three years at Central School of Screech and Trauma [Central School of Speech and Drama] in Swiss Cottage which I found very intimidating. I’d moved into an entirely different environment. I was living in a different city in a series of grubby bedsits in north London and I just went into my shell. I really didn’t know how to enjoy myself - I was so worried about failing that I forgot to live. It was a difficult time but I have no one to blame except myself. But when I look back, I was obviously absorbing stuff. I read constantly and was exposed to Chekhov, Ibsen, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, all these great writers, plus a variety of great directors. I was studying acting and I started to grow up a little bit.

It sounds quite lonely.

No. I wasn’t lonely. I made great friends. It was a delayed adolescence in a way.

But did you ever think, I really don't think I can do this?

All the time. But actors are forever thinking that – I mean, anyone who’s creative thinks that all the time. That’s the motor.

And did you manage to get an agent at the end of it?

No, I didn’t. The majority of my mates got agents and jobs quite quickly and I didn’t get any work or an agent for three years.

That must have been very difficult.

It was, especially because when I left drama school there was this catch 22 situation where in order to get a job you had to have an Equity card and in order to have an Equity card you had to have a job - even though pricks like Derek Hatton [ex deputy leader of Liverpool Council turned TV pundit] were getting them and doing panto. Actually, I kind of jacked it in at one point and went to crew [backstage] at the Manchester Royal Exchange and at the time I probably thought that’s where my future lay.

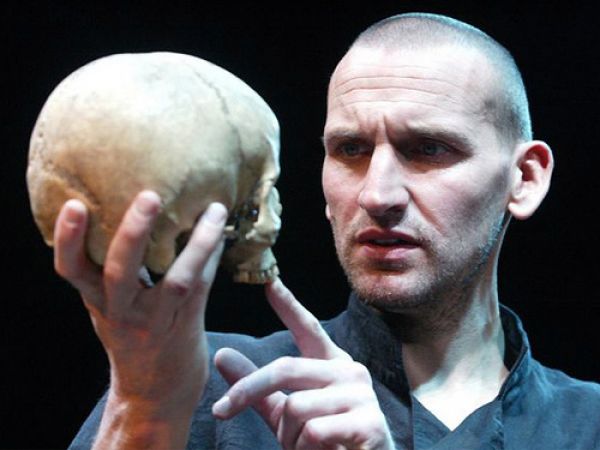

But somebody rang me up and said, “Listen, we’re doing theatre-in-education and we can give you a card as long as you take half a wage, because we really need a driver and you can’t drive.” I got 70 quid a week and my Equity card. And as soon as I got my Equity card, Phyllida Lloyd, who is now famous for directing Mamma Mia!, remembered me from a drama school show, and gave me a job - and I’ll never, ever forget her for it. Apparently she’d said to a number of actors, friends of mine from drama school whom she’d worked with, “Has he not got an Equity card yet?” and for whatever reason – because I’m not an obvious Mexican – she let me play Pablo Gonzales in A Streetcar Named Desire at the Bristol Old Vic. (Pictured above: Eccleston as Hamlet, 2002.)

But somebody rang me up and said, “Listen, we’re doing theatre-in-education and we can give you a card as long as you take half a wage, because we really need a driver and you can’t drive.” I got 70 quid a week and my Equity card. And as soon as I got my Equity card, Phyllida Lloyd, who is now famous for directing Mamma Mia!, remembered me from a drama school show, and gave me a job - and I’ll never, ever forget her for it. Apparently she’d said to a number of actors, friends of mine from drama school whom she’d worked with, “Has he not got an Equity card yet?” and for whatever reason – because I’m not an obvious Mexican – she let me play Pablo Gonzales in A Streetcar Named Desire at the Bristol Old Vic. (Pictured above: Eccleston as Hamlet, 2002.)

It was an amazing experience, not least because I met a great friend, Bob Pugh, who had a huge influence on me and who I share scenes with in The Shadow Line. He’s a writer, an actor – he’s lovely, is Bob.

And then, and this is unheard of, I finished Streetcar on the Saturday and had to be in London the following Monday to start my next job. It was a tiny show called Abingdon Square for Soho Poly, which later transferred to the National. In the meantime, Phyllida gave me another job in Dona Rosita at the Old Vic and I also did Bent at the National with Ian McKellen and Michael Cashman – I was understudying Michael Cashman and playing a very small role.

So that all happened really quickly.

Yes, but these were all really tiny roles. The tiny roles that my mates had been doing back in 1986 when we left drama school.

Didn't you find all this rather dazzling?

No, I’ve never been dazzled by actors. I’m dazzled by footballers, although I think a lot of them behave like morons nowadays. But it was fascinating to watch someone like McKellen in a rehearsal room and on stage – if you’re not going to learn from actors of that calibre, then there’s something wrong with you.

When you’re like a rookie actor – for instance, when you do your first bit of television and you don’t really know what you’re doing - are other actors helpful? Or are they protective of their status, suspicious of newcomers?

No, British actors are very helpful. I've noticed that the British like to be helpful and the tradition of the ensemble is still very prevalent in drama schools. Not that drama school training is essential, because there are lots of great actors who never trained formally, although it is useful in that it gives you an opportunity to fail and to play parts that you won’t get to play in the profession. But yes, I do think that actors like to help each other. Bob Pugh, for example, helped me tremendously. It was tough love though - he’d take me out and get me lathered and say, “Be a bit more disrespectful to the whole process, be anarchic, be free. Don’t be constrained.” And he led by example.

Abingdon Square was with Shared Experience, which works in a very collaborative way.

Very much so. Actually, Nancy’s [Meckler, artistic director of Shared Experience] methods were a little esoteric for me. I’m not knocking them - Nancy was very good to me. I just don’t think I was very good for Nancy’s shows. But what was really good about theatre around that time is that there was a great sense of idealism. I think Nancy is very influenced by Mike Alfreds and I think – well, he’s a genius, his theatre is extraordinary, as is Declan Donnellan’s work. All those directors, including Nancy, very much relied on the audience’s imagination and intelligence rather than giving them the whole thing on a plate - addressing the mystery, I suppose, of performance with minimal props. Theatre is a live event and if that’s not at the core of your work, if you’re not admitting that it’s live and it has to be different each night and it has to live in the moment, then it’s dead theatre.

And then you broke into films.

Yeah. Not having worked for three years, it was famine then feast. Suddenly there was a British film being made in an era when there were even less British films being made than there are today and I got the lead. So I went from absolute zero to the lead in a British film. I played Derek Bentley in Let Him Have It.

Watch the trailer for Let Him Have It

Did you ever meet any of the Bentley family?

I did. I got close to Iris and her daughter – not surprisingly, they were using the film as part of their campaign to clear Derek’s name. The thing is, at the time I was quite young, 26, and I didn’t admit to myself that it was an onerous task but it was - playing a figure whom, quite understandably, had become a sainted figure to his family. And he was a big guy, 19, with a learning age of 11, possibly lower, and heavily medicated on antique medication for epilepsy which emphasised his disability because he was heavily doped and yet still going through all the things adolescents go through. It was a big task and the only time I’d worked in front of a camera before was on two small television jobs - Morse and Casualty – and there I was, the lead in a feature film. At the time I thought I was taking it all in my stride, but looking back I wasn’t. I was panicking, it was too much. What is it they say? That the key to success is that some people are born to expect, some people are born to accept, and I think I’m probably the latter.

Really? I don’t get that impression at all.

I never expected success. I’ve worked with people who’ll turn round and say they’ve just got the lead in a big film with a complete sense that it was always going to happen and, like it or not, that kind of confidence is probably what you need to be a major star. I don’t think I have that but I have always wanted to have integrity.

You never have done a commercial, have you?

No, I haven’t, but I do understand that some people have to. It’s a very personal decision that, but I just didn’t want to end up selling cornflakes.

Tell me about Our Friends in the North.

Our Friends in the North, a nine-part series for the BBC, was an amazing opportunity for an actor – I think I was 30 – to play a character from the age of 19 until his mid-fifties. Very rarely seen on television, likewise on stage – unless you’re playing Peer Gynt and then it's usually split between actors. In a way, I saw it as an opportunity to go back to drama school and get paid for it.

It was a play originally, wasn’t it?

Yes, but it was massively expanded and altered [for television]. And of course, it was a brilliant bit of writing – a political, state-of-the-nation piece – except that it wasn’t, it was more a saga of people’s lives, the failure of the Left in Britain and housing policy in Britain. Certainly my character [Nicky Hutchinson], was obsessed with how we house the poor. But for me, the heart of the piece was this fantastic father-son relationship, played by myself and Peter Vaughan - both idealists, both embittered and unable to communicate. Then, at the moment when the son finally feels able to confront the father and ask for an explanation for all the coldness and the distance over the years, it’s too late - the father has Alzheimers. To watch Peter Vaughan play that part was an education. (Pictured above: Eccleston, Gina McKee, Mark Strong and Daniel Craig in Our Friends in the North.)

Yes, but it was massively expanded and altered [for television]. And of course, it was a brilliant bit of writing – a political, state-of-the-nation piece – except that it wasn’t, it was more a saga of people’s lives, the failure of the Left in Britain and housing policy in Britain. Certainly my character [Nicky Hutchinson], was obsessed with how we house the poor. But for me, the heart of the piece was this fantastic father-son relationship, played by myself and Peter Vaughan - both idealists, both embittered and unable to communicate. Then, at the moment when the son finally feels able to confront the father and ask for an explanation for all the coldness and the distance over the years, it’s too late - the father has Alzheimers. To watch Peter Vaughan play that part was an education. (Pictured above: Eccleston, Gina McKee, Mark Strong and Daniel Craig in Our Friends in the North.)

So it was a good experience?

Oh yeah. If you’re working on a good script, then you’re happy. And if you’re not, you’re not happy.

And you started to get cast in Hollywood films. Did you go over to LA and do all the rounds of meetings?

Well, I was on people’s radar because of Let Him Have it and Jude, so I did a bit of that and I believed every word they said to me and came away with nothing because there’s a culture of lying. People over there will give you the impression you’ve got the job when you haven’t. It’s just the way in that town, a town that’s full of fear. And then I played a kind of stock panto villain in a film called Elizabeth and they all thought [in Hollywood] that I was a bad-ass, so I got offered a couple of bad-ass roles and, against my better judgment, I took the money.

That sounds as if you regret it.

No, I don’t regret the money - if I did, I’d have given it back. It was a strategic move. I thought, if I do these films...

And which films are those?

Oh, I’m not going to name them. People can dig them out themselves, I’m not going to publicise my worst performances. But the money allowed me to come back and do some really interesting British television, like Flesh and Blood [written by Jimmy McGovern], which was one of my favourite projects - we did that for two conkers and a marble and it won awards all over the world. It was a BBC Two drama where I played a character who had been adopted as a baby and when he has a child of his own, a biological switch is thrown and he wants to find out about his own background. He discovers that both his mother and his father have a learning disability and actually, although obviously it was pleasurable, they had no idea they were having sex or that they’d conceived a child, but because both of their conditions were from childhood injuries, my character had no genetic predisposition. It was a fantastic story and again, like Our Friends in the North, it was about a man trying to connect with his father. It’s obviously been a theme – in my work, that is. I’m perfectly well connected with my own father.

Do you read your reviews?

Yes, I do, although I always think, when a critic dies, all it will say on their headstone is: "Here lies – whoever - Critic." That’s it. Terrible.

So you don’t take reviews to heart?

Yes, I do. Sometimes they’re right. Sometimes they quite correctly identify things you suspected were wrong – I’m talking about theatre critics – but sometimes it’s just personal and sometimes it’s just about the fact that they’re on the dinner party circuit in north London with a select bunch of actors, usually the Oxbridge lot.

How do you find LA? You seem so English to me, it’s difficult to imagine you being comfortable in LA.

Hmm… well, I find that slightly patronising. I think the reason you consider me English is just because I’m from the North.

Apologies, but that's really not what I meant. I mean, I consider myself very English – I know I come across that way to Americans. I don’t drive, for a start.

I lived in Los Angeles before I could drive - you have to use the yellow buses and then you see the underbelly of Los Angeles, the reality, and that’s really useful. I like Los Angeles – to visit. I love how professional the industry is. I’m not in a box over there, I can play anything – I’ve played Amelia Earhart’s navigator, I’ve played a tramp in Heroes. I’ve auditioned for all kinds of roles over there, I’m just an actor. You’re not bound by the class system.

But you just said it was a town full of fear.

Yeah, of course, but you have to navigate that. You have to understand that that is probably all part of the American dream. People in the film industry always want to impart enthusiasm and positivity, even if it misleads people - just in case you walk out the door, get another job and become very successful. And there’s great work to be done in America and they like British actors - a lot. Partly because we’re cheap but largely because we’re very good at what we do, and that goes for British directors too.

You seem to have been more astute when choosing British films, working with the likes of Michael Winterbottom.

Of all the films I’ve done, Jude is the one that I’d stand by, the one I’d like people to come back to. The rest is much of a muchness.

When you’ve made films that you haven’t been pleased with, do you look back and remember the shoot as an unhappy experience?

Not necessarily. I quite enjoyed working on Elizabeth because I got to see Cate Blanchett become what she is and I think she’s a pretty extraordinary actor. She’s also great to work with. And I got to work with Joe Fiennes, which was good fun. We were an eclectic bunch: Geoffrey Rush, Richard Attenborough, Eric Cantona - although I didn’t speak to Cantona because I’m a huge Manchester United fan so I was very shy. I wasn’t entirely happy with the celebrity casting aspect either, because I had mates who’d trained for three years at drama school and were scratching around trying to make a living.

Watch a video of Christopher Eccleston and Cate Blanchett in Elizabeth

OK. The elephant in the park. Doctor Who.

Well, that’s all in the past now.

When you were initially approached –

I put myself forward. I approached the writer and said, “I’d like to play this part.” I did the first series which was a great success and I am very proud of it.

So how did you hear about it?

Through the grapevine. So I said, “I’ll do that. And they [the BBC] were like, “What?” And that’s precisely what it needed.

But why did you want to do it?

I had just worked with Russell T Davies on Second Coming [in which Eccleston plays a video store assistant, who also claims to be the Son of God] which I thought was a good piece of television and I thought, he’s a good writer, he could do something with that programme [Doctor Who], which actually I had paid no attention to as a child and a young man. I was always out playing football and you know, the doctor was very RP and very authoritarian because it would appear that in this country, if you’re the least bit intellectual or sensitive or poetic, you have to speak with an RP accent.

So when I first heard about it, I was out running - I run a lot – and I was trying to think of a way into the Doctor’s character. So I was thinking, Time Lord, what does Time Lord mean? And I thought: he’s falling through time, he’s never at home and he’s lost - I could play that. It was a way in. So I emailed Russell. And of course, although it’s all about the ride and the fun and all of that, part of the fascination that the show had is something to do with that character. Yes, he’s heroic and he’s brave, but he’s also an outsider and there are all sorts of minority groups who fasten on the Doctor, precisely because he’s an outsider who insists on inclusiveness. So, without turning it into a Ken Loach film, I thought I could do something with that. And I’d always acted for adults, never for children and children have much better taste than adults because they don’t censor themselves. That’s what I feel anyway. If a child says to you, “That programme was rubbish,” it was rubbish. If an adult says it was rubbish, you think, well, you’ve probably got an agenda. So I wanted to work for the most exacting audience there is - and I’d worked for their parents you see, so it worked beautifully for the BBC. (Pictured above: Eccleston as the Doctor in Doctor Who.)

So when I first heard about it, I was out running - I run a lot – and I was trying to think of a way into the Doctor’s character. So I was thinking, Time Lord, what does Time Lord mean? And I thought: he’s falling through time, he’s never at home and he’s lost - I could play that. It was a way in. So I emailed Russell. And of course, although it’s all about the ride and the fun and all of that, part of the fascination that the show had is something to do with that character. Yes, he’s heroic and he’s brave, but he’s also an outsider and there are all sorts of minority groups who fasten on the Doctor, precisely because he’s an outsider who insists on inclusiveness. So, without turning it into a Ken Loach film, I thought I could do something with that. And I’d always acted for adults, never for children and children have much better taste than adults because they don’t censor themselves. That’s what I feel anyway. If a child says to you, “That programme was rubbish,” it was rubbish. If an adult says it was rubbish, you think, well, you’ve probably got an agenda. So I wanted to work for the most exacting audience there is - and I’d worked for their parents you see, so it worked beautifully for the BBC. (Pictured above: Eccleston as the Doctor in Doctor Who.)

There was huge excitement about the return of Doctor Who. I mean, it really was a big deal. Were you shocked by all the fuss and the brouhaha?

Not at all. When you’re in the industry you come to expect it. It’s all PR generated.

So you didn’t feel overwhelmed?

No, why would I after all the things I’ve done? I’d been working in television for 15 years by then.

Lennon Naked must have been similarly challenging – in that, he is someone that millions of people all over the world feel a connection with, a sense of ownership in some cases.

And everybody knew exactly how he sounded and exactly how he looked which made the job that much more difficult.

Not to mention that people are hugely attached to him.

Yeah. Well, they are very attached to the Doctor. They are also, as I found out, very attached to Jesus Christ. But Lennon Naked was a beautiful script by a writer called Robert Jones and something that I felt I had to do. We had 18 days to do 90 minutes of period television. I was in every scene and it was a very difficult shoot but I’m glad I tried it. The cowardly thing to have done would have been to say, “No, I’m not going to try that,” but life’s too short.

Tell me about your latest project, The Shadow Line.

The Shadow Line is a series directed by Hugo Blick and it is, superficially at least, a procedural crime drama, the investigation of a murder by both the police and the criminals. What it’s actually about is a kind of meditation on human motivation and morality and the grey areas that we all exist in. There’s also a great deal of contrasting of lives and human behaviour with a lot of black humour and a strong thriller element. It’s very cinematic for television, noir-ish, almost. It’s been inspired a great deal by Seventies American films such as All the President’s Men and The Parallex View, those kind of paranoic thrillers, very layered with anti-heroes.

My character is called Joseph Bede and Lesley Sharp (pictured left with Eccleston) plays my wife, who suffers from early-onset dementia, and it’s that aspect of my character’s life that presents the audience with a problem really, because this is a man who traffics heroin, although he’s by no means a traditional villain. Up until the drama begins he’s only ever been behind the scenes doing the books but because of the death of Harvey Wratten, which is the central murder that the series kicks off with, my character has to step forward and front an operation. He’s not suited for it. He’s not physically violent, he isn’t acquainted with knuckle dusters - he’s been a book-keeper. He’s completely out of his depth but he needs to make a certain amount of money to ensure the care of his beloved wife – she’s his childhood sweetheart and they’ve been married for nearly 30 years.

My character is called Joseph Bede and Lesley Sharp (pictured left with Eccleston) plays my wife, who suffers from early-onset dementia, and it’s that aspect of my character’s life that presents the audience with a problem really, because this is a man who traffics heroin, although he’s by no means a traditional villain. Up until the drama begins he’s only ever been behind the scenes doing the books but because of the death of Harvey Wratten, which is the central murder that the series kicks off with, my character has to step forward and front an operation. He’s not suited for it. He’s not physically violent, he isn’t acquainted with knuckle dusters - he’s been a book-keeper. He’s completely out of his depth but he needs to make a certain amount of money to ensure the care of his beloved wife – she’s his childhood sweetheart and they’ve been married for nearly 30 years.

That sounds slightly similar to Accused, in that, again, it's morally ambiguous. You played a man who wasn’t bad – in fact, he was a very good man in many ways, but he had his flaws and he made a stupid mistake.

That character was Willy Houlihan, a plumber who loved his wife very much - again they were childhood sweethearts. He also loved his daughter very much and she was getting married and he wanted to give her the best day of her life precisely because she’s the kind of girl who would never ask for the best day of her life, that was his reasoning. He thinks his other two children are selfish but she’s not, so he wants to reward that. He finds some money in a taxi but instead of returning it, he gambles it in order to increase it and pay for his daughter’s wedding. At the same time, unfortunately, he’s having an affair with a much younger woman and his life unravels very quickly. It’s quite biblical in its way.

I’ve worked with Jimmy six times now – Cracker, Hillsborough, Hearts and Minds, Sunday, The Accused and Heart – and he said to me very early on [adopts Scouse accent], “When I’m writing the characters, what I’m doing is I’m looking for the pure motive and it doesn’t exist.” It’s very Raymond Chandler, it’s what Marlowe is always looking for – the pure motive.

And you know what - are there any wholly good men? Are there any wholly bad men? I’ve not found any and I certainly don’t see one when I look in the mirror.

- The Shadow Line is on BBC Two from Thursday, 5 May at 9pm

Find Christopher Eccleston on Amazon

Find Christopher Eccleston on Amazon

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...

Chris, it's great reading