Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929, V&A | reviews, news & interviews

Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929, V&A

Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929, V&A

Ballets Russes appeals to all the senses: an explosion of colour and movement

Museum shows don’t often evoke a sense of smell, but without even trying, this Ballets Russes exhibition has visitors’ nostrils flared. The show is – intentionally – a feast for the eye, and even for the ear, with ballet scores (sometimes rudely overlapping) playing in every room. But smell?

True, Diaghilev was said to have worn Mitsouko perfume, and sure enough, a flacon sits in one of the galleries. But more to the point, look carefully at the costumes. The first response is – how incredibly gorgeous. Heavy with embroidery, with appliqué, with silk, with satin, velvets, lace, gilt wire, even leather, canvas and oil-cloth, the second thought is, how did they move?

How did Nijinsky, one of the greatest dancers of all time, with reports of astonishing elevation, amazing, floating jumps, how did he get in the air when wearing a costume made out of silk, satin, gold knit, gold paint and mother of pearl? Or another, made of metal thread and cotton jersey, silk, brass decorations, papier-mâché, cotton and gauze, all topped off with a brass headdress. Still others (pictured right) were embroidered with floss, velvet flocking, beading or metal ornaments.

How did Nijinsky, one of the greatest dancers of all time, with reports of astonishing elevation, amazing, floating jumps, how did he get in the air when wearing a costume made out of silk, satin, gold knit, gold paint and mother of pearl? Or another, made of metal thread and cotton jersey, silk, brass decorations, papier-mâché, cotton and gauze, all topped off with a brass headdress. Still others (pictured right) were embroidered with floss, velvet flocking, beading or metal ornaments.

Which brings us to smell. Dancers, to put it bluntly, sweat like pigs. Today’s costumes are lycra, cotton or rayon; they get thrown in the washing machine and the dryer, and are ready to put on again. Even so, most backstage areas are pretty whiffy. In the 1920s, before deodorant, imagine taking off a wringing wet costume after a matinee, only to have to put it on, no cleaner and little dryer, just two hours later.

It is to the credit of the V&A’s exhibitions that the costumes, so impossibly glamorous, so thrillingly conceived and designed, show their wear and tear; that the films, the narratives, the captions all permit us to think of these objects not merely as beautiful things, but as components in an art form that moved, that lived and breathed.

The show is filled with drawings, watercolours and paintings of costumes and sets. Some, such as those of Bakst, are well known – although never before in such profusion as in this opulently completist show – but still they continue to astonish. The second room of the exhibition is filled with dramatically spotlit costumes in the centre of the room, with more costumes around the sides. But it is Bakst’s drawings that still manage effortlessly to dominate the whole room: sinuous, voluptuous, promising and teasingly elusive, they remain peerless.

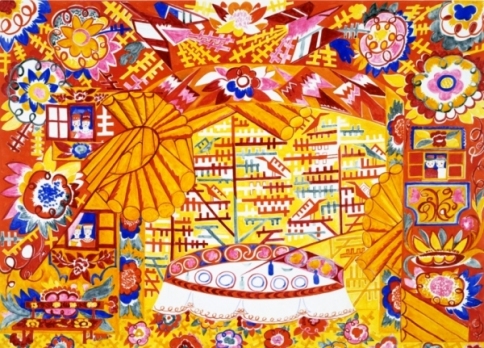

Further on, it is Natalia Goncharova who is the star. Her breathtaking designs for Le Coq d’or (pictured above) are not just beautiful stage designs: they are great art. As are her drawings for Les Noces. And her costume designs, like the drawing of Shah Shahriar, for The Sleeping Princess. And indeed everything she touched: long appreciated as a fine Modernist artist, I’m not sure this exhibition doesn’t show her to have been one of the greatest colourists of the 20th century. (And given that the costumes in the next room are by Matisse, that is saying something.) Mikhail Larionov, her husband and artistic partner, is also finely represented, as with his costumes for Chout (main picture, above).

As a dance-lover, I do have a few grumbles. The curators seem to be worried that their audience won't be interested in dance. The exhibition has some wonderful films of the very earliest Ballets Russes dancers, but, while there are dozens of films today of performances with Ballets Russes sets, costumes and choreography, we are shown very few of them, and when we are, they remain only tiny snatches, and very often with someone (usually Howard Goodall) standing in front and talking. I’m always interested to hear what Goodall has to say, but why may I not watch the Royal Ballet performing Les Noces, or The Firebird, to complement the costumes in the show? Or see the New York City Ballet dancing The Prodigal Son, to go with the Rouault drawings on display? Why, instead of a performance of Les Biches, is there a 1960s BBC film "based on" the idea of Les Biches, but without the sets, costumes or, oh yes, without the choreography – so, let’s face it, it's not Les Biches at all.

This is all the more peculiar, given how much care has been lavished on building up a picture of Diaghilev’s hotbed of creativity, and how well it succeeds. Picasso’s monumental front-cloth for Le Train bleu looms large, but equally evocative are the photographs from the rehearsals of Parade, to go alongside his Cubistic costumes. And, finally, the ephemerality of the entire art form is encapsulated in one single display case: there are two sets of boots, for character dances, and two tiny pink satin pointe shoes; "satin, cotton, hessian, cardboard and glue", says the label. All this radiant beauty, all this astonishing creativity, all the technique, the bravura, the artistry and technical skill of the dancers: at the end of the day, all this can be reduced to satin, cotton, hessian, cardboard and glue. That is the true miracle of the Ballets Russes, and of dance.

- Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes at the V&A until 9 January, 2011

- Diaghilev on theartsdesk

- Find Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes, edited by Jane Pritchard and Geoffrey Marsh, on Amazon

- Find Sjeng Scheijen's Diaghilev: A Life on Amazon

Buy

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

...