It shows you just how much Kenneth MacMillan changed ballet in this country that 1960's The Invitation, with its onstage rape, sexual grooming and child abuse, can act as the reassuring classic at the heart of the new Royal Ballet triple bill which opened on Saturday. The Invitation should be – and is – a shocking piece, but when bracketed by Wayne McGregor's brand new Obsidian Tear and Christopher Wheeldon's 2012 Within the Golden Hour, two particularly vapid examples of contemporary ballet, MacMillan's ballet de moeurs, for all its darkness, has a comforting solidity. It reassures us that ballet is still an important art form, capable of substance, depth and expression.

The setting is a Riviera villa somewhere in the early 20th century, though the murky green lighting makes it look rather more mid-Victorian than Roaring Twenties – but then it's precisely the collision of the two cultures, the uneasy coexistence of prudishness and licentiousness, that The Invitation indicts. The opening scene is heavily suggestive, as the lady of the house covers up naked statues with modest dust sheets – only for a group of teasing adolescents to take them off again and force Francesca Hayward's innocent Girl to put her face to a male statue's crotch. The childish romance between the perfectly cast Hayward, a dainty slip of a thing in a white frilly dress, and her cousin (the equally well cast Vadim Muntagirov) has barely been expressed, in a luminous little pas de deux which culminates in a poignantly angelic lift, before it is submerged in the corrupting atmosphere of the adult party. The evening's entertainment is a sleazy masque of male cocks fighting over a female (the lithe and elegant Mayara Magri), and all the couples are playing dangerous sex games.

Gary Avis and Zenaida Yanowsky are the older couple who will spoil youth's innocence, the man a stocky figure tense with aggression which he takes out on his beautiful, needy wife. In the programme, Avis speculates that his character's rape of the young Girl might be a mistake (because she, fascinated by his admiring gaze, comes to him in a nightgown) but I'd call that wishful thinking, if not victim-shaming (pictured right: Hayward and Avis). The choreography shows no seduction gone wrong but a violent, and inventively varied, series of violations, in which the Girl is entirely in the older man's power: she barely even touches the floor as he throws her about in ingenious lifts which, however disturbing to watch, are also brilliantly original (worlds away from the bland grinding of Christopher Wheeldon's recent Strapless).

Yanowsky's encounter with Muntagirov is bloodless by comparison, showing a gendered double standard in which the male youth is barely scarred by his brush with adult sexuality, while the girl is ruined not just by her physical trauma but by the social stigma which will result – predicted in the chilling scene in which Yanowsky clocks what has happened and chooses solidarity with her husband, rather than his victim. However mannered its representation, this is a fully realised world and the setting for a heartfelt social critique, which makes one feel all over again the thrill of MacMillan's talent for taking ballet to very real places full of intelligible action.

Tear can be pronounced to mean either a teardrop or a ripNext to The Invitation, McGregor's Obsidian Tear appears as a particularly unintelligible blend of abstraction and woo-woo. One of the two mildly atmospheric Esa-Pekka Salonen pieces which form the score is called Nyx, after a primordial night goddess in Greek mythology, while obsidian is a black stone associated with ritual magic, and also with a Native American story about trapped warriors who leap off a cliff to their doom. Tear, if you are wondering, could be pronounced to mean either a teardrop or a rip; the homography, McGregor reveals in the programme, helps suggest the violent quality of grief, also picked up in the title by Salonen's other piece, Lachen verlernt, the German for laughter unlearned or forgotten.

What any of this has to do with what happens on stage is an utter mystery – doubtless intentional, since McGregor always likes to claim he's one step ahead of everybody else. In the programme note, he proclaims, "I want meaning to be readily accessible, but at other times remote. I want the audience to navigate an individual journey through those moments because that reflects our experience of living. We don't 'understand' everything all of the time."

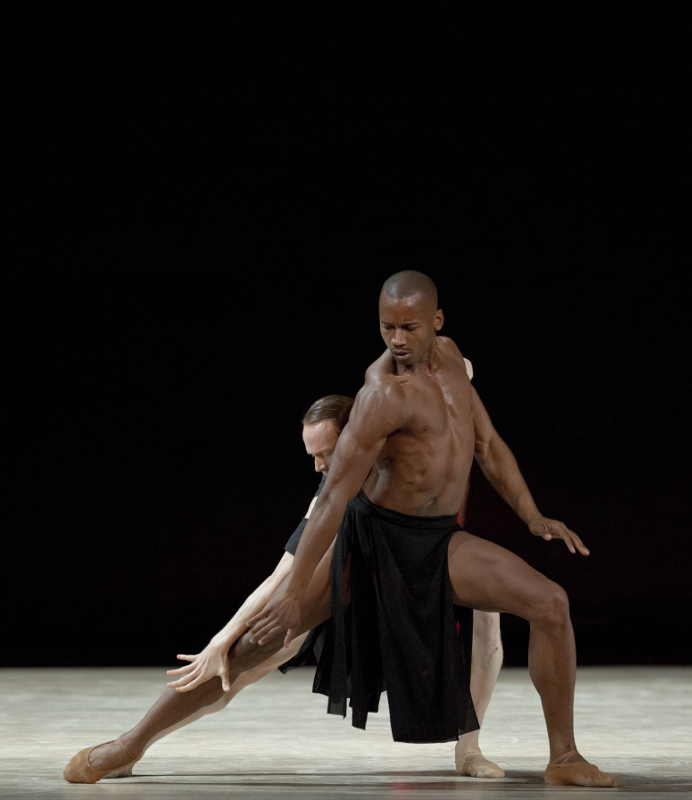

Presumably this means I shouldn't object to Obsidian Tear's incomprehensibility, but I can't help it: the piece is spectacularly weird. My best guess is that Edward Watson is the brooding leader of an all-male cult, to which Matthew Ball brings elegant Calvin Richardson as a sacrificial victim of whom he (Ball) then becomes fond. This leaves Ball, understandably, sad after Watson makes him throw Richardson into a molten crevasse. Yes, really. The purpose of the cult is unclear: it might be sex (Watson seems to have it off with preening beauty Eric Underwood, pictured left with Watson), but it definitely requires the wearing of designer clothes "distilled" to their essence by Katie Shillingford - who reveals that a surprising number of big-name international fashion designers are inspired by judo pants. The dance is interesting in parts, with lovely expressive arm gestures for Ball and Richardson in the beginning duet and some inventive group dynamics in the second section, but mostly the piece seems wilfully esoteric.

Presumably this means I shouldn't object to Obsidian Tear's incomprehensibility, but I can't help it: the piece is spectacularly weird. My best guess is that Edward Watson is the brooding leader of an all-male cult, to which Matthew Ball brings elegant Calvin Richardson as a sacrificial victim of whom he (Ball) then becomes fond. This leaves Ball, understandably, sad after Watson makes him throw Richardson into a molten crevasse. Yes, really. The purpose of the cult is unclear: it might be sex (Watson seems to have it off with preening beauty Eric Underwood, pictured left with Watson), but it definitely requires the wearing of designer clothes "distilled" to their essence by Katie Shillingford - who reveals that a surprising number of big-name international fashion designers are inspired by judo pants. The dance is interesting in parts, with lovely expressive arm gestures for Ball and Richardson in the beginning duet and some inventive group dynamics in the second section, but mostly the piece seems wilfully esoteric.

Wheeldon's Within the Golden Hour is, by comparison, inoffensive, but there's little more to be said for it than that. It's pretty and fluid, like most things made for San Francisco Ballet (its original commissioners), it's set to bland orchestral wallpaper by Ezio Bosso, and the Royal's competent dancers go through the motions with no obvious sign of heart or soul engaged. Contemporary ballet, performed by one of the world's top dance companies, should be so much better than this.

Add comment