Who qualifies as an older dancer? Given that a professional dance career usually runs from about 17 to 35, anyone continuing to dance past 40 can expect comments on their age and speculation about when they'll stop – see Sylvie Guillem, Wendy Whelan, Leanne Benjamin, Carlos Acosta. People who are physically extraordinary and have interesting minds are worth watching at any age, but public performances by dancers over 50 are still very rare indeed. So hurrah for the Elixir Festival at Sadler’s Wells this weekend, which is all about older dancers, and put its money where its mouth is by filling the main stage with them on Friday and Saturday nights.

Two pieces by Swedish choreographer Mats Ek and his wife Ana Laguna bookend the show, both excellent arguments for the power of these two performers in particular and works with older dancers in general. In neither piece is it quite clear what’s going on, but the strength of their on-stage chemistry makes it a pleasure to try and work out the story. In Potato, a sack of the tubers is the only prop; in Memory (main picture), the set is almost a living room, with standard lamp, television, couch and chair. In both, Ek and Laguna seem to play – or sometimes argue – immersed in their own world, a place full of in-jokes, affection and history. It feels like voyeurism, but a happy kind, peering into the private dynamic of a couple who’ve been together for decades and still enjoy one another’s company. A danced duet that’s not all or only about sex is rare, but - as these two fascinating, whimsical, inscrutable pieces show – both excellent and delightful.

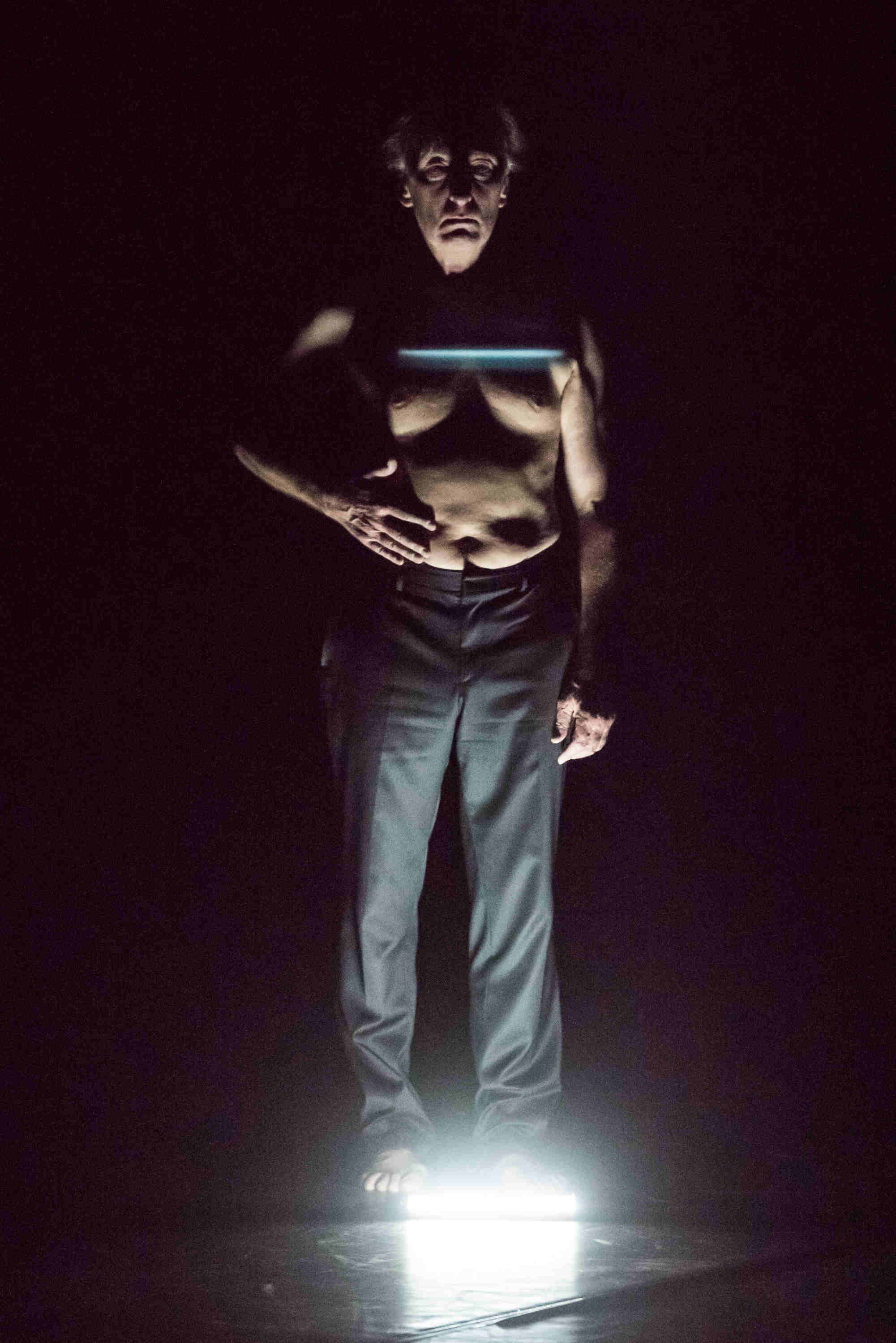

There is no-one better qualified than a Pina Bausch dancer to show that even in the physically demanding world of dance, decades of experience can trump limber youth. Dominique Mercy has been with Tanztheater Wuppertal since the beginning, and the solo he performs here, That Paper Boy – un solo pour Dominique Mercy (conceived and directed by a younger Tanztheater colleague, Pascal Merighi) is in many ways classic Bausch – rich, strange, immersive, and often obscure. Mercy’s age is highlighted – literally, when he picks up a fluorescent tube that casts the contours of his 64 year-old chest and face into shadowy relief (pictured right) – but whether that age limits or enriches him is left open to question.

There is no-one better qualified than a Pina Bausch dancer to show that even in the physically demanding world of dance, decades of experience can trump limber youth. Dominique Mercy has been with Tanztheater Wuppertal since the beginning, and the solo he performs here, That Paper Boy – un solo pour Dominique Mercy (conceived and directed by a younger Tanztheater colleague, Pascal Merighi) is in many ways classic Bausch – rich, strange, immersive, and often obscure. Mercy’s age is highlighted – literally, when he picks up a fluorescent tube that casts the contours of his 64 year-old chest and face into shadowy relief (pictured right) – but whether that age limits or enriches him is left open to question.

In some ways he seems dependent: reading his words always from pieces of paper; calling for his glasses; bursting into a frenetic, wonderful dance when a younger man does, but stopping dead when the other guy disappears; standing stock still while a cello candenza rings out, as if all the vitality in that sound can’t find its way into his body to be expressed in movement. His words suggest melancholy or regrets – “we didn’t talk too much; we thought we understood each other” - or confusion - “can you repeat? it’s getting complicated”. But against all these perhaps predictable narratives of age is set the deep charisma of Mercy himself, his absolute command of the stage, and the joy of watching him dance. As a childlike voice sings a hipsterish little song with the lyrics “one day we’ll be old”, Mercy bursts into shimmering life, sometimes skipping or whirling in a pastiche (or just rediscovery?) of juvenile pleasure, sometimes just doing his own, asymmetric, absurd things – and the youthful singer’s glib invocation of being “old” seems trite. It’s long and sometimes frustrating to watch, but That Paper Boy is the evening’s standout, displaying a fertility and power that only Eks and Laguna come anywhere near matching.

The other offerings all have, more or less, an air of contrivance about them. An excerpt from Hofesh Shechter’s In your rooms (pictured left) performed by the Sadlers Wells Company of Elders, a group of over-sixties who regularly take dance classes at the Wells, fails to move – although the live music, with spiky and atmospheric strings and percussion, is a plus. About Lo que me dio el agua, intended by Carmen Aros and Sonia Uribe to interpret Frida Kahlo’s painting ‘The Two Fridas’ (1939), the less said the better. The close-ups of Kahlo’s work that form the backdrop are far and away the best thing to be seen here.

The other offerings all have, more or less, an air of contrivance about them. An excerpt from Hofesh Shechter’s In your rooms (pictured left) performed by the Sadlers Wells Company of Elders, a group of over-sixties who regularly take dance classes at the Wells, fails to move – although the live music, with spiky and atmospheric strings and percussion, is a plus. About Lo que me dio el agua, intended by Carmen Aros and Sonia Uribe to interpret Frida Kahlo’s painting ‘The Two Fridas’ (1939), the less said the better. The close-ups of Kahlo’s work that form the backdrop are far and away the best thing to be seen here.

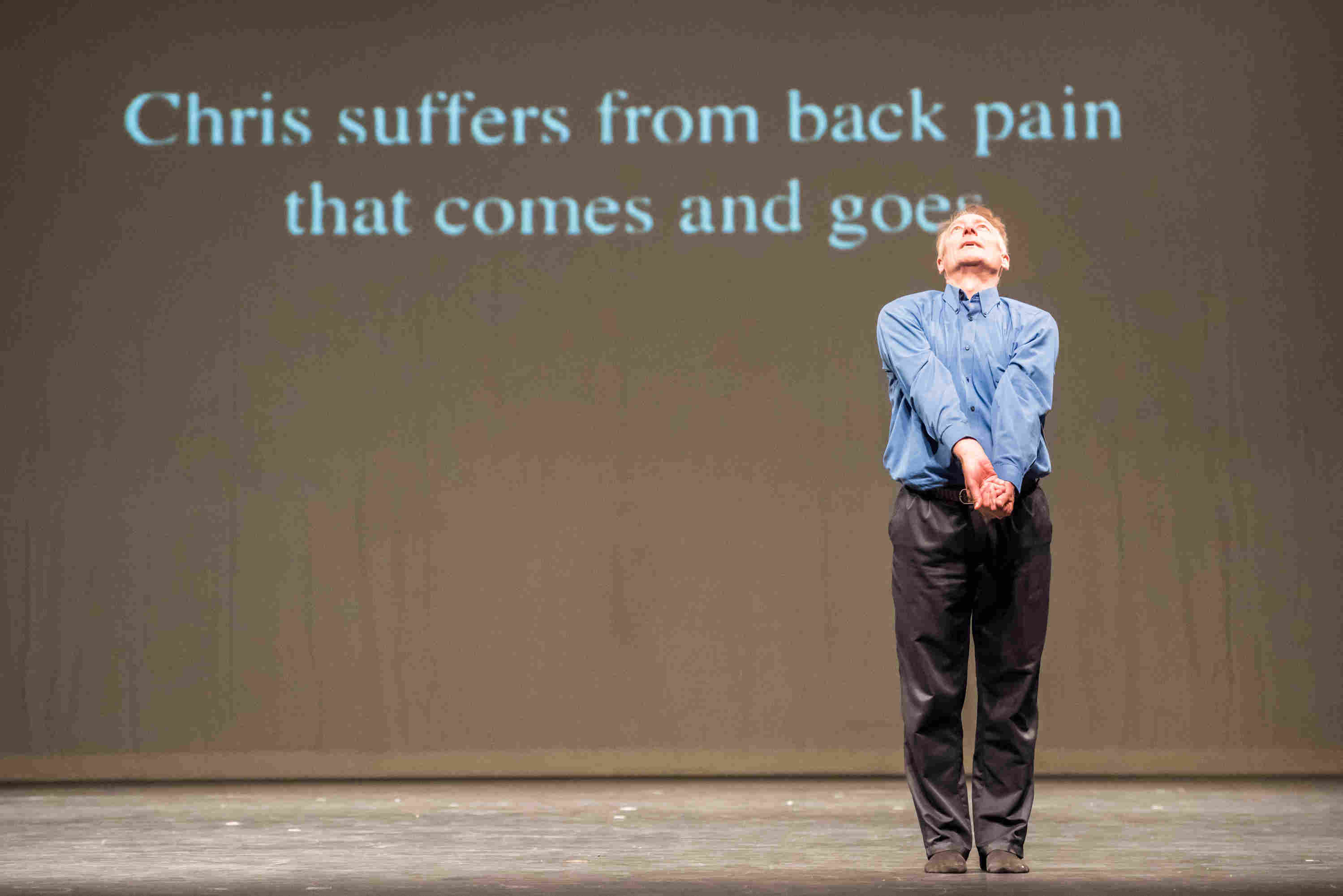

The Elders Project has a lot more to offer: a group of ex-professional dancers (many from the London School of Contemporary Dance), aged from 54 to 70, are brought together on stage by former Royal Ballet dancer Jonathan Burrows and composer Matteo Fargion. In deadpan recitative, Fargion sings snippets of information about each dancer, some factual (“the first room Geraldine danced in was in the local community hall”), others funny (Chris (pictured right) didn’t mind his back pain once “he realised he was a genius dancer....stuck in the wrong body”). The dancers appear as individuals, both through the stories we hear about their lives, and through the solos they perform – Brian Bertscher gleefully sending up classical ballet; Kenneth Tharp jumping and spinning with a huge smile, Namron lifting Linda Gibbs with a totally deadpan face. By the time we are told their dates of birth, the audience likes them enough to whoop and cheeer; their age becomes a fact that adds to what we already know and like about them, rather than the first characteristic we notice. This is unlikely to have much mileage as a piece for the repertoire, but it’s a delightful demonstration of all that is good about the Elixir Festival – as well as being laugh-out-loud funny.

The Elders Project has a lot more to offer: a group of ex-professional dancers (many from the London School of Contemporary Dance), aged from 54 to 70, are brought together on stage by former Royal Ballet dancer Jonathan Burrows and composer Matteo Fargion. In deadpan recitative, Fargion sings snippets of information about each dancer, some factual (“the first room Geraldine danced in was in the local community hall”), others funny (Chris (pictured right) didn’t mind his back pain once “he realised he was a genius dancer....stuck in the wrong body”). The dancers appear as individuals, both through the stories we hear about their lives, and through the solos they perform – Brian Bertscher gleefully sending up classical ballet; Kenneth Tharp jumping and spinning with a huge smile, Namron lifting Linda Gibbs with a totally deadpan face. By the time we are told their dates of birth, the audience likes them enough to whoop and cheeer; their age becomes a fact that adds to what we already know and like about them, rather than the first characteristic we notice. This is unlikely to have much mileage as a piece for the repertoire, but it’s a delightful demonstration of all that is good about the Elixir Festival – as well as being laugh-out-loud funny.

Some words read by Burrows during The Elders Project serve as a pointed and poignant epigraph for the whole evening: “This is a room full of people who still think that dance has meaning. It’s not about nostalgia – but something has disappeared. Everything disappears in this stupid artform! Which is why we like it.”

- The Elixir Festival continues at Sadler's Wells till Monday 15 September.

Add comment