Someone sharp as a whip thought hard about the price-fun balance of the latest Royal Ballet triple bill. An accountant, probably. Deep inside the cloisters of the Royal Opera House, they said: “Now top price stalls are £97 each for Romeo and Juliet, that’s nearly £200 a pair. Interval wine at £6 a glass, £24. A programme, train fares from - say - Windsor at £15 each, plus taxis. That’s £260 for their evening. So for the triple, if we’re going to charge £37.50 top whack, we can hardly give them more than a third of the fun, can we?”

You gets what you pays for. The new bill must cap most memories of drear evenings I've spent inside Covent Garden. Three ballets as one, a programme pitched to win media PR headlines about being modern and up-to-date, urban reality meets ballet, bang-on visual installations, etc. And so we got grey, grey, and grey, a triple dose of chugging angst and pampered distress, where evidently large amounts of production money have been spent on video sets and rain curtains and orchestral commissions all of skilfully leaden pessimism, and thank you for the subsidy. What ever happened to fun and dynamism, people?

One ballet was new, by in-house hopeful Jonathan Watkins, the other two were 2008 novelties by Kim Brandstrup and Wayne McGregor. Possibly it was hoped that Watkins’s premature birth in the main house would be helped by being harnessed to two known parties, both characteristic of their makers but neither of them too exciting to overpower him, and all roughly similar. There are certain flaws in that reasoning, not least from the audience’s point of view.

The principal, and very real interest, in Kim Brandstrup’s Rushes - Fragments of a Lost Story second time around is the music, the remarkable job done by Michael Berkeley on stitching together the fragments of Prokofiev’s lost film score for Queen of Spades, sounding gorgeously through-composed under the baton of Daniel Capps. This is a potently dramatic musical river on which Brandstrup floats an abstract, fragmentary plot drawn from Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (if more resembling Carmen), about a man torn between two women, madonna and whore in type.

The principal, and very real interest, in Kim Brandstrup’s Rushes - Fragments of a Lost Story second time around is the music, the remarkable job done by Michael Berkeley on stitching together the fragments of Prokofiev’s lost film score for Queen of Spades, sounding gorgeously through-composed under the baton of Daniel Capps. This is a potently dramatic musical river on which Brandstrup floats an abstract, fragmentary plot drawn from Dostoevsky’s The Idiot (if more resembling Carmen), about a man torn between two women, madonna and whore in type.

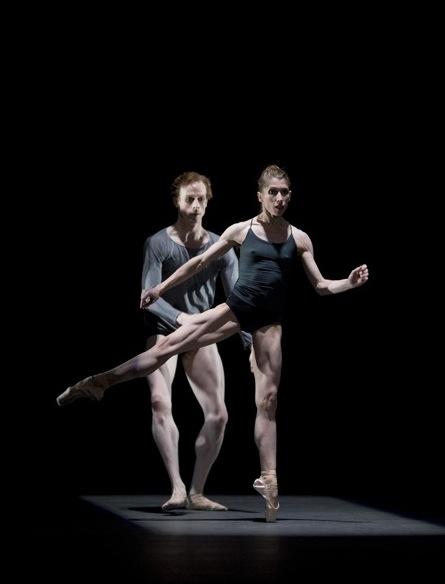

The impressionistic staging and soft-edged choreography, while emotional and true, are easily occluded if not given clearly committed motivation by its performers. Carlos Acosta is not naturally at home in writhing impotence and a hideous baggy brown T-shirt, and I felt he was phoning in his opening night show, while Laura Morera has acquired stilted mannerisms in her acting of the femme fatale - their relationship had no sting. The one vibrant theatrical reality on stage was Alina Cojocaru (pictured right by Bill Cooper) as the gentle stay-at-home girl: her final pas de deux both beseeching and comforting Acosta was drenched with need - the highlight of the entire evening, as it proved. There is, though, a second cast to see in this ballet, so different that it is almost a different ballet.

I tried hard to focus below on the real dance, but to no avail - my eyes kept skidding back up to the digital frieze

McGregor’s Infra is the one with the digital frieze by Julian Opie, with pixelated people ambling overhead andante and real dancers knotting below them furioso. First time round last year, I was much more compelled by the digital than the real. This time I tried hard to focus below on the real, but to no avail - my eyes kept skidding back up to the Opie. They do so little, those strolling, imperturbable yet mysteriously individual figures, but somehow I want to decode them. The real dancers expend much double-jointed energy below, but give so little away apart from their stamina and muscularity that they don’t intrigue. The mechanical scrub of Max Richter's piano quintet enhances the air of don't-care. A climactic surprise is the eruption of a large crowd into the stage around a girl dancer who collapses in misery - a coup contrived to tick the box "big finish".

This was the context in which young Jonathan Watkins offered his main-house debut As One. He describes his ensemble piece as “an optimistic strike against the modern threat of conformity” - but this is as conformist a piece of costive contemporary Covent Garden ballet as any. It is clad in the trappings of office blocks and trendily bleak city flats, yet it’s using a choreographic language that felt to me like someone who is really of the David Bintley or Christopher Bruce vernacular ballet persuasion being forced through a more angular mould - not his style. Once again, the score struck me as the more interesting feature, Graham Fitkin's eclectic dialogue of Penguin Café-ish working drive and private uncertainties needing someone with more of Paul Taylor or Jerome Robbins' acerbic observational eye.

McNally made it fine and eloquent, her body rippling with contractions and pleas for release

As One wraps complications around a simple idea: the opposition of an urban couple (Laura Morera and Edward Watson) occupying a white sofa and watching TV or other people’s windows to stave off the tedium of their relationship, and vignettes of what the people in the far-off windows (Simon Daw’s eye-catching video scenery) are doing. The “windows” of the block disgorge little snapshots of minimally interesting activity, costumed in orange: a party in a kitchenette, five lads jitterbugging in roadworker tracksuits, a girl shivering in fear over some kind of audition, and a chap footing it featly in front of the Footsie index (Steven McRae typecast in pirouettes).

The only scene that struck me as having genuine thrust and imagined shape was Kristen McNally’s anguished waiting room solo, while fellow auditionees come and go quietly. It could be a hospital waiting room, or an actors’ audition, or an exam, or an annual company interview. Whatever, McNally made it fine and eloquent, her body rippling with contractions and pleas for release while a piccolo trilled out a nostalgic little cry, but it remains only a vignette within a cliché. There's a school of gardening that says you should harden your seedlings and tender plants outside and the devil take the hindmost. Watkins must face the frost like a man.

Add comment