Leslie Phillips: 'I can be recognised by my voice alone' | reviews, news & interviews

Leslie Phillips: 'I can be recognised by my voice alone'

Leslie Phillips: 'I can be recognised by my voice alone'

Saying goodbye to the actor famous for saying hello

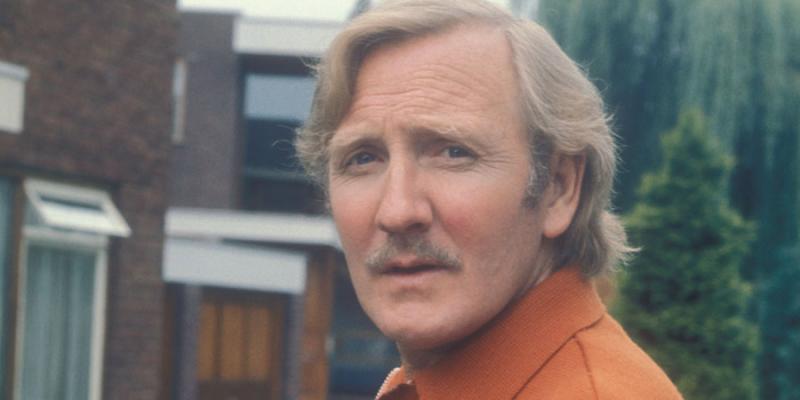

Leslie Phillips would have known for half a century that at his death, which was announced yesterday, the obituaries would lead with one thing only. However much serious work he did in the theatre and on screen, he is forever handcuffed to the skirt-chaser he gave us in sundry Carry Ons and Doctor films and London bus movies.

Those famous roles came out in his middle years. Before that he had been a very busy child actor. Then in his fifties Phillips took the courageous decision to do no more broad comedy. There was a stomach-churning period of inactivity when he was widely presumed to have died, but the roles for nabobs, mandarins and stuffed shirts started to roll in. Often cast as Lord Chief Justice this, Viscount that, Professor the other, wasn’t it about time he had a K of his own? "Oh I've not got anything like that," he said glumly.

His conversation was peppered with such accolades for the "marvellous" and "lovely" and "super" actors he had worked with. He told several stories about times when so and so told him he was wonderful, or how he broke records with such and such a show. It's not that he was vain, but while the Lothario years made him far more visible than most of his contemporaries, they seemed to have punctured his professional self-esteem. Of course there were fringe benefits: "If I have an altercation with somebody in a car,” he said, “as I do occasionally, it ends up with them wanting my autograph.”

Involuntarily, I cased his home in Maida Vale for evidence that the stereotype was not a complete fiction. He wore a discreet gold chain round his neck, and a raffish mat of white curls. He kept a beautiful 1965 Mercedes 220 SE Cabriolet convertible in the basement garage, On the way out to the garden we passed a bronze statuette depicting some mythical damsel in distress. Proprietorially, almost absent-mindedly, he rubbed her idealised breasts, and you could almost hear James Robertson Justice blowing a fuse.

He was delightful company. This is a transcript of some of that conversation.

JASPER REES: Where does the voice come from?

LESLIE PHILLIPS: My father was a worker. He was a very sick man and therefore his career was stunted. My mother was always looking after him and he died when he was only just 41 or something. We were always short of money. Cockney family. All that was my background, still is, but going on stage altered my life, altered my friends. The voice came because it had to come. When you went on the stage in those days in the Thirties you couldn't become an actor with a regional accent. So because I worked with marvellous people they helped by association. They were wonderful to me, and I took elocution lessons. They used to send me up at school when I began to speak proper, but the big thing was association, being with people, and in the end I didn't even realise I was dropping it. And then the capping off was the army, because I got a commission and then you become an officer and it became a bit army officerish – "How d'you do, old boy", a bit like that – and then I dropped that after the war. The tone is not put on or assumed.

How much ability did you have at 10?

None. My mother saw an advertisement in the paper and we had no money and my brother and sister had started working. It was the Italia Conti. I didn't go straight away. She wasn't like a theatrical mum. She was the opposite. I went up later with her and I did a little bit of a play and it was pretty awful. The only thing was I threw my overcoat over my shoulder like a toga and that got me in. But what I spoke was no good. I've always been quite inventive, so maybe this sign of it was there. I had to earn money to pay the fees. I paid my own fees from what I earned. She taught you and acted as agent. I did some bloody good plays as a kid, a few good movies. Nothing startling. I worked with all the top greats from 10 right through to when I joined the army. So I had a marvellous eight years of education. I did Peter Pan with Anna Neagle. I was the wolf. I was in a play with John Gielgud when I was a boy called Dear Octopus by Dodie Smith. I was in the original play with Leon Quartermaine and Marie Tempest. I was about 14.

How did your theatre career get going after the army?

Vivien Leigh was very helpful to me. I was in The Doctor's Dilemma with her with a fantastic cast of people when I was 17. I joined the army from there. That was when she started going round with Olivier. He used to come into the theatre at the Haymarket. In fact I was understudying, playing a small part, and she was smashing, a lovely lady, beautiful. When I came out of the army I got a little bit doing Anna Karenina, and Austin Trevor was a lovely actor, he saw me on the set, and he said, "Have you seen Vivien? You must see her, she would love to see you." Three years had gone by. I'd gone from 18 to 21. He pulled me over. “Vivien, look who's here.” "Leslie, you're alive! What are you doing? We're going to Australia, Larry and I. Would you like to come? Come and do an audition." She got me to audition with him, and then they offered me a job and I was thinking of getting married at that point and I had another job offered me in Swiss Cottage at the Embassy doing rep, and I saw him and he said, “Yup, we'll take you, but don't ask me to take your lady. I can’t take any more ladies. If you don't come, some other time." They were smashing. I didn't go. I stayed, I got married and my career blossomed here. I don’t regret an awful lot really. I worked with him later. And then of course I worked with Joan Plowright in The Cherry Orchard and he helped me terribly. Gave me a wonderful note. "Positive! Even if you're bad, go on and do it. It becomes good."

How did your career on the big screen begin?

I did some bloody good big movies long before I did these comedies. But people have forgotten those. I went to Hollywood before I did three Carry Ons, three Doctors and oodles of others. But I was in Hollywood in a big lovely movie called Les Girls with Gene Kelly and Kay Kendall. That was in '55. Then I did a lot of very good films just after I came out of the army at Ealing, all dramas. But that's gone. I think what started it was I did a couple of movies for Cubby Broccoli and they were big American co-productions. Irving Allen produced them. I went in to see him and he said, “Where's the moustache?” And I said, “I only had that for a part, because I can't stand spirit gum.” He said, “I want the moustache.” So I said, “OK, I'll grow another one.” And that started that image thing. I think it was almost the moustache that did it. Spirit gum is a spirit which forms a gum which you use for sticking on hair, but it stings and I've got quite sensitive skin. And when you pull it off it's horrible. I grew one because I hated spirit gum. There was always a leading character in English films and you wore that mantle. It was Ian Carmichael who wore it for a long time and I followed in his wake. When you do one you do another and another. If you succeed in comedy and you have timing and all those things people say, “Oh, must do another one.” But if you succeed in drama it doesn't do that. It then started to look as though I would never play a drama, so I had to force my way back. I made over 100 films.

Is there a trace of biographical truth in the caddish character you played in the 1960s and ‘70s?

What, womanising, you mean? No, everybody thinks that. I like women. I think I've led almost a blameless life. I've had a few girlfriends and they've always been longstanding, but I've never been that image of hopping out of bed with one and into bed with another. I think in some cases without doubt I become like the parts I play. And maybe the parts I played became me. I don't think I have ever really overcome it with the public. I think with one's peers I've certainly overcome it. I still get an enormous amount of letters. If I go along the street, people see me and go “Oh hello.” I get immediate recognition, but from those films. I think television is the fault. All those movies go round the bloody world. Perhaps I wouldn’t mind so much if I got paid for them. But you're just building up nicely, doing some nice things and suddenly on comes another one. It sort of irritates slightly. There's a large audience in this country, in fact in the world, that only watches old films. They don't watch good new television or go to the theatre. This immediate recognition, which of course people flatteringly said you haven't changed. Obviously I've changed, but there's a kind of image that one still has. The sound too, apart from this throat. I can be recognised by my voice alone.

You haven't often played likeable characters.

Oh. Oh. I suppose so. I have played a lot of bastards, but they're more rewarding. Perhaps I'm a bastard. Perhaps it comes out in these parts. All those jolly comedies, people never thought I was a bastard. They thought I was a real devil. Women loved it and men admired it, so I never made enemies like some of these toughies who get beaten up in pubs.

How did you approach filming bedroom scenes?

I was in that swim when it started to come in. All that you didn't have your foot on the ground any more, and nudity came in during my successful time in television. I was always bloody helpful to the girls who had to go through it. They were always scared. I've never played anything like I've seen. Not serious sex, but I've had to cope with girls who've had to take their tops off and run around the room and they'd be scared. I've often helped them actually, but not taken advantage.

Leslie Phillips, 20 April 1924 – 7 November 2022

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment