DVD: Every Picture Tells a Story | reviews, news & interviews

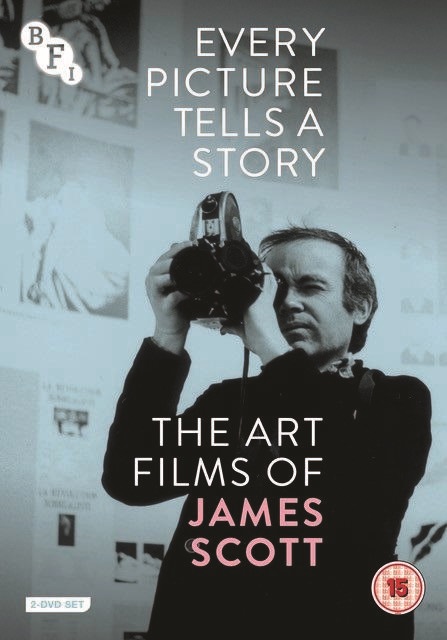

DVD: Every Picture Tells a Story

DVD: Every Picture Tells a Story

The art films of James Scott: a very mixed anthology, dating from 1966 to 1983

James Scott’s filmography is wide-ranging, including the 1982 short film A Shocking Accident, based on the Graham Greene story, which won an Academy Award the following year, and other works on social questions.

The longest, Every Picture Tells a Story, is a 1983 biopic based on the early life of his northern Irish father, William Scott (1913-1989) who moved from Scotland to Enniskillen as a teenager, studied art in Belfast, then went on to London and a vastly successful career. The film even has a role for the very young and beautiful Natasha Richardson, as an art teacher, Miss Bridle, her first credited appearance (main picture).

Several of the documentaries may require a degree of specialist knowledge, particularly true of the exploration of British Surrealism, Chance, History, Art which does include, however, an indulgent but fascinating interview with Jimmy Boyle. The convicted murderer, sentenced to life imprisonment, turned to art and became a cause célèbre for his passionate adherence to its importance; he was released after 15 years, moving on to a career as an artist and writer.

Several of the documentaries may require a degree of specialist knowledge, particularly true of the exploration of British Surrealism, Chance, History, Art which does include, however, an indulgent but fascinating interview with Jimmy Boyle. The convicted murderer, sentenced to life imprisonment, turned to art and became a cause célèbre for his passionate adherence to its importance; he was released after 15 years, moving on to a career as an artist and writer.

Although both well-known surrealist aphorisms and well-known Surrealists are evoked, the majority of artists shown in the film are not particularly familiar. There is also a sequence of tracking shots of the huge and ground-breaking exhibition at the Hayward Gallery, Dada and Surrealism Reviewed, which examined surrealist publications on a par with surrealist art. But the sophistication of art documentaries has moved up many notches since then, especially in bringing exhibitions to the big screen.

The four films concentrating on particular artists have a great deal to offer. The Great Ice Cream Robbery is a fascinating study of Claes Oldenburg, the highly original Swedish-American pop artist, in London for his 1970 Tate exhibition (the title came from an incident outside the Tate when an ice cream cart was moved on for obstruction and accidentally turned over). Oldenburg is himself quietly hilarious. Some of the most quietly subversive elements are the splendidly wary and sceptical middle-aged gallery warders, whose body and facial language indicates they are not wholly convinced by the art that is being installed. However, Scott was a bit too clever by half; he decided to make a split-screen narrative, almost impossible to replicate at home, and he swings from Tate scenes to following Oldenburg and his partner Hannah Wilke as they wander by the Thames. Is the exhibition and the artist the subject, or their visit to London?

The Richard Hamilton visual essay from 1969 is equally intimate, even thrilling

Scott describes his films about living artists as collaborations. The most straightforward is the black and white Love’s Presentation (1966), with a young David Hockney, all peroxide hair and black-rimmed glasses, being introduced by a wonderfully prim (BBC received pronunciation) description about the ways in which the public was as fascinated by Hockney’s personality and northern accent as by his art.

We see Hockney embarking on the sequence of prints he made to illustrate the poetry of CP Cavafy, and his voice-over disarmingly explains how he chose Cavafy’s poems about love rather than history. We see the whole process, from Hockney at home in charmingly controlled chaos, carefully drawing in the prepared plates, arranging acid baths on the balcony (so as not to be affected by the fumes), and eventually going to the professional printers at Editions Alecto. The viewer is made wonderfully aware not only of the concentration, skill and technique of the process but also the sheer devotion and enthusiasm of the artist. It is replete with informative insight, and curiously personal.

The Richard Hamilton visual essay from 1969 is equally intimate, even thrilling, as the popular sources from advertising, film stills and the like that Hamilton explored with such wit and verve morph into actual paintings, collages and prints. He explains in detail the reversal of the film still from Bing Crosby’s I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas. His print of Mick Jagger arrested and on the way to jail is interspersed with newsreel of the incident, and we see the art dealer Robert Fraser and the girlfriend Marianne Faithfull – all so young and slight to cause such a huge furore. This is a wonderfully intelligent introduction to the work of one of Britain’s most perspicacious and pertinent artists.

The American artist RB Kitaj, who came to England to study on the GI bill, first to Oxford and then to the Royal College of Art in London, is another subject. Talented and painfully sincere, the controversial Kitaj, who like Hockney passionately espoused representational art, could not help his fancy verbal pyrotechnics, obscuring rather than explicating his artistic passions. Kitaj was hardly ever filmed: made in 1967, the sheer rarity of his presence here makes Scott’s film invaluable.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment