In his exclusive half-hour-plus interview for distributor Second Run, the affable Tsai Ming-Liang makes a striking admission: “I make very uncommercial films.” Viewers of the extra will most likely have just finished Goodbye, Dragon Inn (Bú sàn) (2003), Ming-liang’s feature-length exploration of precisely everything that comes of those pesky “uncommercial films”. That is, a decrepit, old picture-house on the outskirts of Taipei, hosting its last ever screening – of King Hu's 1967 sword-fighting classic Dragon Inn – complete, or incomplete, with leaky ceilings, and a thoroughly depleted audience.

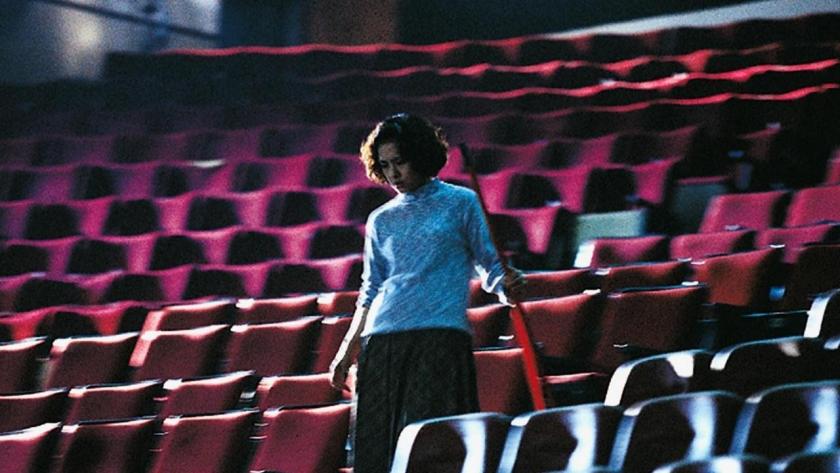

But, what if a film didn’t have to be commercial to be enjoyable? It would have been easy, perhaps, for Ming-Liang to produce a documentary about cinema-going, about going to this cinema (the Fu-Ho) in particular, or even to offer his own take on Hu’s wuxia classic. Far more impressive is this surreal world-within-a-world, a world stripped of action and shorn of dialogue, in which time seems to stand still – or limps slowly along, in rhythm with the stilted metronome of the Fu-Ho’s disabled attendant (Chen Hsiang-Chyi), one leg longer than the other, meandering ghost-like through its empty corridors.

The film opens with a shot of the cinema screen, the off-facing angle immediately recognisable to anyone who’s spied a bootleg recording, or watched mobile-phone footage of a television screen, and imbues the feature with a furtive, illicit quality. We are offered glimpses of glimpses – brief scenes of the attendant behind a screen, or looking through a curtain. These are set against a series of longer, drawn-out shots, Ming-Liang resting his gaze on the Fu-Ho’s hidden taboos: projection rooms, or the men’s toilets – and by which, we understand, this largely vacant cinema has acquired a subversive second-life, as a cruising-ground for gay men, on the lookout for a quiet, intimate encounter. On screen, at least, no such encounter occurs, true-to-form for a film that toys and teases with its audience, those longer scenes set alight with our own intense anticipation of an event that rarely, if ever, arrives. Even the film’s first passage of dialogue (one of only two throughout), is postponed until over half the run-time has already passed. That, too, is uttered in a cramped back-corridor, hemmed-in beneath the audible whirr of an electric fan.

The film opens with a shot of the cinema screen, the off-facing angle immediately recognisable to anyone who’s spied a bootleg recording, or watched mobile-phone footage of a television screen, and imbues the feature with a furtive, illicit quality. We are offered glimpses of glimpses – brief scenes of the attendant behind a screen, or looking through a curtain. These are set against a series of longer, drawn-out shots, Ming-Liang resting his gaze on the Fu-Ho’s hidden taboos: projection rooms, or the men’s toilets – and by which, we understand, this largely vacant cinema has acquired a subversive second-life, as a cruising-ground for gay men, on the lookout for a quiet, intimate encounter. On screen, at least, no such encounter occurs, true-to-form for a film that toys and teases with its audience, those longer scenes set alight with our own intense anticipation of an event that rarely, if ever, arrives. Even the film’s first passage of dialogue (one of only two throughout), is postponed until over half the run-time has already passed. That, too, is uttered in a cramped back-corridor, hemmed-in beneath the audible whirr of an electric fan.

Goodbye could not be more different from the iconic martial-arts feature to which it owes its title. Nevertheless, Ming-Liang succeeds in achieving a fluid synthesis between the two films – the former’s 90-minute run-time taking place entirely within the screams, trumpet flares, and exaggerated death-scenes that comprise the latter’s soundtrack. Yet, despite its near-ubiquitous audio presence, there are few images of Dragon Inn. Instead, the director prefers to focus on its watching audience. With this comes more wryly familiar touches: the couple eating too loudly, the woman resting her feet on the back of the chair in front, the man who arrives late (and leaves early). Seeing them, we are reminded of all the obligatory quirks and oddities that accompany a trip to the cinema – and without which the experience wouldn’t be the same.

“It’s almost as if the building is another member of the cast,” Ming-Liang fondly suggests in that same interview. This near-human appreciation is Goodbye’s defining emotion, a poetic tribute to a place that is far more than the sum of its parts, whose end and closure will always feel premature – an act that the film subtly, satirically stages, when the Fu-Ho’s projectionist (Lee Kang-Sheng) breaks back into the very office that the attendant has departed, for what we understand to be the final time. Those craving more will, at least, have an excellent (if limited) set of special features – as well as the director interview, there's a booklet with essays from critic Tony Rayns and acclaimed director Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Ming-Liang’s poignant entry to the Lucca Film Festival’s Twenty Puccini project, Madame Butterfly (2008).

Add comment