One of the world’s leading architectural photographers, Julius Shulman was the subject of a show at London’s Photographers’ Gallery this autumn, “Altered States of America”. That title surely alluded to the visual modernism that changed the face of that country over the course of the 20th century, which Shulman, working in close tandem with the architects concerned, captured over a career of almost eight decades, in California especially.

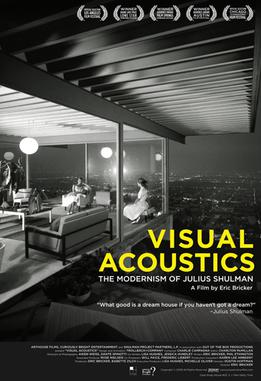

Visual Acoustics, Eric Bricker’s documentary about that career, was originally released in 2008, the year before Shulman died, just a year or so short of his centenary, and it’s a richly affectionate tribute to the photographer, showing him still at work in his final years and very much absorbed in the milieu – Los Angeles, in particular – that he had made his own. Bricker’s title remains allusive, hinting perhaps at how Shulman managed to catch the resonance of architectural form in his images, especially through light. Given the fact that the greater part of his work depicts domestic architecture – houses built for individual clients – Visual Acoustics is a valuable, and winningly personal introduction to environments otherwise inaccessible to the public (it’s not unlike the massive Taschen tribute volume that we witness being readied in the film’s second half).

While the tone is broadly adulatory, the insights are real. Alongside a host of architectural professionals – practitioners and critics alike – designer and film director Tom Ford draws attention to the fact that, “The houses [that he photographed] are not nearly as beautiful as in Julius Shulman’s pictures.” Shulman certainly brought his own perspective to what he depicted, adorning the interiors of Richard Neutra, the first architect with whom he worked (their collaboration started in 1936) with domestic props brought from his own home to suggest a lived-in environment (Neutra, mysteriously, would hover on the edges holding branches, to emphasise nature).

While the tone is broadly adulatory, the insights are real. Alongside a host of architectural professionals – practitioners and critics alike – designer and film director Tom Ford draws attention to the fact that, “The houses [that he photographed] are not nearly as beautiful as in Julius Shulman’s pictures.” Shulman certainly brought his own perspective to what he depicted, adorning the interiors of Richard Neutra, the first architect with whom he worked (their collaboration started in 1936) with domestic props brought from his own home to suggest a lived-in environment (Neutra, mysteriously, would hover on the edges holding branches, to emphasise nature).

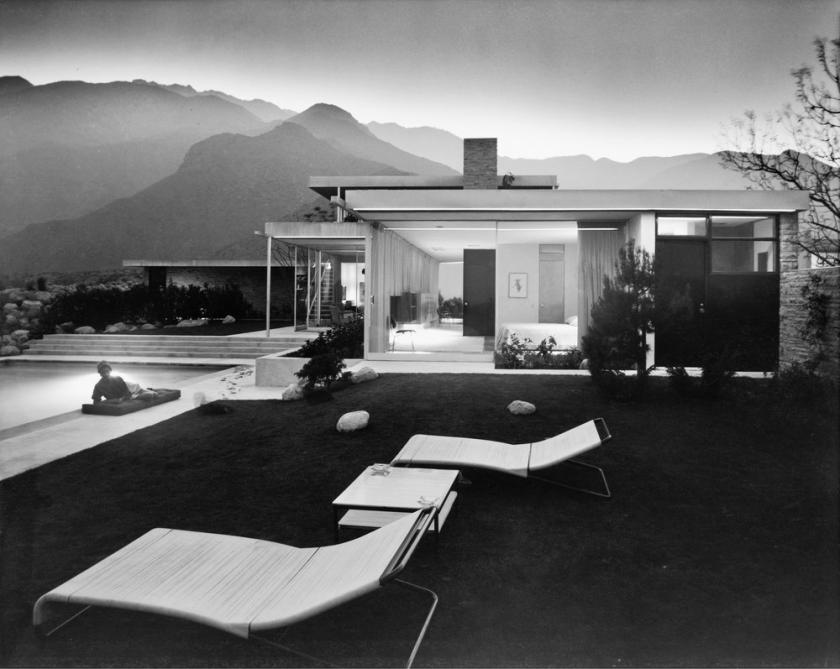

The fate of some of these once iconic buildings has not always been kind: we witness the lengthy ongoing restoration (after neglect that almost saw it demolished), using Shulman’s images as a guide, of the Kaufman House in Palm Springs (main picture), in its time almost a calling card for the Californian way of life. Changing tastes played their own role in Shulman’s career, too, one which took him far from California, most notably to Mexico and Brazil and collaboration with Oscar Niemeyer and Abraham Zabludovsky. He hated post-modernism as an architectural style to such an extent that its arrival prompted him to retire (temporarily, as it turned out).

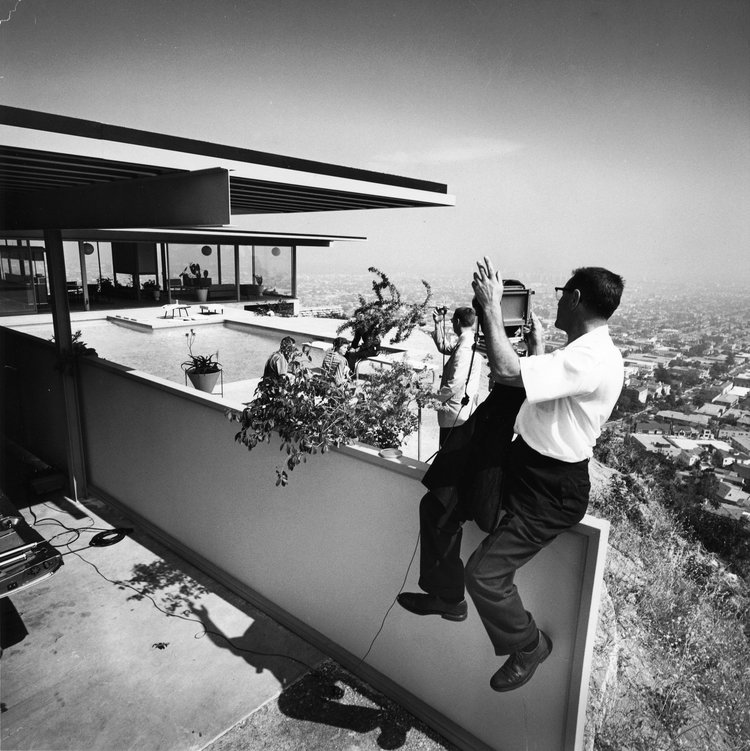

But the sense of enduring connections remains potent, nowhere more so that in his classic image of Pierre Koenig’s Case Study House No. 22 (poster image, pictured above; Julius Shulman on the shoot, pictured below). It was still lived in by the owners who had commissioned it, making for some affectionate nonagenarian banter, while Hollywood cinematographer Dante Spinotti dropped by to film within its spaces. (Another nice Tinseltown-linked link emerged – how frequently the houses of another Shulman collaborator, the architect John Lautner, have stood in for lairs for movie baddies.) One particularly eminent tribute (not from Visual Acoustics but the Photographers’ Gallery exhibition) to Koenig’s Case Study House came from Norman Foster, who commented on this work – implicitly, on Shulmann’s image – that “seems so memorably to capture the whole spirit of late 20th century architecture”: “If I had to choose one snapshot, one architectural moment, of which I would like to have been the author, this is surely it.”

More specialist architectural connections are nicely brought together by some inventive design and elements of animation, as well as a spare voiceover from Dustin Hoffman. It makes accessible the links backwards between Shulman’s world and the European origins of Neutra and fellow Austrian architect Rudolph Schindler and their intersections with the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as forwards to the likes of Albert Frey and E Stewart Williams (there’s much veteran drollery when Shulman reunites with the latter). Less explored, but surely no less significant, is how Shulman, working equally for specialist publications such as Arts & Architecture and mass-readership titles like Good Housekeeping, introduced the American public in the widest sense to the new “innovative lifestyle”. In the process, too, he “scouted” out the work of new architects, as Frank Gehry recalls here, although in that case, ironically, Shulman’s enthusiasm didn’t bring the usual career-advancing results.

More specialist architectural connections are nicely brought together by some inventive design and elements of animation, as well as a spare voiceover from Dustin Hoffman. It makes accessible the links backwards between Shulman’s world and the European origins of Neutra and fellow Austrian architect Rudolph Schindler and their intersections with the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, as well as forwards to the likes of Albert Frey and E Stewart Williams (there’s much veteran drollery when Shulman reunites with the latter). Less explored, but surely no less significant, is how Shulman, working equally for specialist publications such as Arts & Architecture and mass-readership titles like Good Housekeeping, introduced the American public in the widest sense to the new “innovative lifestyle”. In the process, too, he “scouted” out the work of new architects, as Frank Gehry recalls here, although in that case, ironically, Shulman’s enthusiasm didn’t bring the usual career-advancing results.

What of the man himself? There’s a lovely opening encounter with Shulman in the fecundly overgrown garden of his LA home – “my God is nature,” he says – that might seem in contrast to the sharp lines of the architectural styles that made him famous, though it’s in tune with the early concerns for ecology and the environment that saw him help to establish “Project: Environment USA”. Bricker’s film meanders somewhat around its subject, but the cumulative portrait that emerges, of the man and the environment that he both captured and helped to shape, is personably satisfying.

Add comment