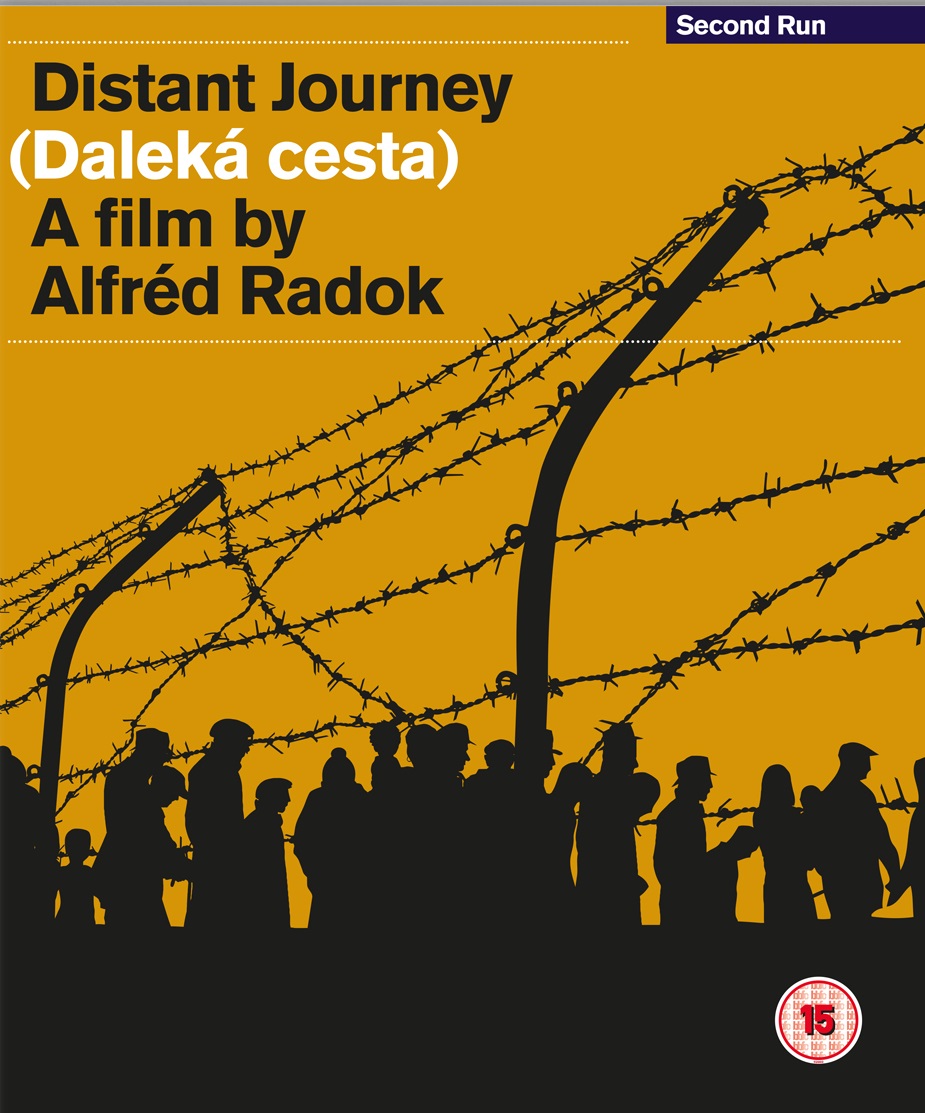

Czech director Alfréd Radok’s Distant Journey (Daleká cesta) has an unprecedented place in the history of cinema of the Holocaust. Initially released in March 1949, it has been called the first fictional treatment of the Jewish experience during the Nazi era, appearing less than four years after the liberation of the Terezin (Theresienstadt) transport camp, where the greater part of its action is set. As the world struggled to assimilate its recent history – if, indeed, assimilation of any kind can ever be possible – the fact of such a film appearing, from within a society that had been so embryonically connected to those events, after so short an interval remains remarkable.

Its creators drew closely on their own experience. Distant Journey was based on a story by Erik Kolár about his own experience in Terezin, and it was there that members of Radok’s immediate family perished, including his father (the director was half-Jewish). That he came to direct the film, based on a treatment of Kolár’s original sketch, was itself surprising for a figure then only in his mid-thirties, and known to date for his work in experimental theatre. He would make only three features in all before his death – he left Czechoslovakia after the 1968 Soviet invasion, settling in Sweden – with theatre becoming again the centre of his life (among other achievements, he was the inventor of Prague's Laterna Magika).

The action of Distant Journey encompasses the duration of the war years, from the early anti-Semitic prejudice that appeared with the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia through to the liberation of Terezin in 1945. The film’s central character, Hana (Blanka Waleská), is a Jewish doctor dismissed in the opening scene from the hospital where she works on racial grounds. For her family, as for others, emigration still remains a possibility, albeit a distant one, but Hana resolves to stay – “This is my language, my home, my people,” she responds when such a choice is suggested. Her marriage to Toník (Otomar Krejča), a fellow doctor and a Gentile, initially seems to offer a degree of protection not afforded to her immediate family, but in time the dreaded transports, relocation instuctions, arrive for her too, the prelude on the path that led, for most, towards extermination.

The action of Distant Journey encompasses the duration of the war years, from the early anti-Semitic prejudice that appeared with the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia through to the liberation of Terezin in 1945. The film’s central character, Hana (Blanka Waleská), is a Jewish doctor dismissed in the opening scene from the hospital where she works on racial grounds. For her family, as for others, emigration still remains a possibility, albeit a distant one, but Hana resolves to stay – “This is my language, my home, my people,” she responds when such a choice is suggested. Her marriage to Toník (Otomar Krejča), a fellow doctor and a Gentile, initially seems to offer a degree of protection not afforded to her immediate family, but in time the dreaded transports, relocation instuctions, arrive for her too, the prelude on the path that led, for most, towards extermination.

As the story develops, Radok stretches his stylistic range significantly. From the relatively conventional feel of early scenes (though there are touches of artistic bravado), he introduces more unsettling and allusive visual elements that colour the narrative, before Terezin becomes the central location, that ghetto-camp presented in almost phantasmagorical terms as a warren of angled, dark locations. From something close to naturalism, Radok moves towards an increasingly frenzied expressionism.

It’s a spectrum further complicated by his use of documentary footage, charting the rise of Nazism (with material from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will) through the wider conflict unfolding across Europe; the juxtaposition is achieved by use of a second small screen that appears periodically as a picture-in-picture, the main window alternating between the particulars of the immediate story and brief snatches of its loose historical context.

Radok’s sheer technical achievement (and no less, those of his cinematographer, Josef Strecha) becomes increasingly striking as the culmination of liberation approaches, felt in an expressionist disorientation that veers towards the surreal. Therein, arguably, lies the main charge that can be levelled against the film, that it aestheticises experience far away from anything close to whatever reality may have been: the final scenes have an almost ecstatic carnival atmosphere to them, while Jiri Sternwald’s score can seem over-crafted towards tension, as well as fostering an occasional melodrama that is hardly there in the action.

The unusual status of Terezin itself, as a ghetto environment that was both transit camp and nominally “showcase” location (subject to inspection by the International Red Cross and the like, as one late scene references) may play a role in that, while a strangely neutral coda seems uneasily tacked on. Any final decision on the crucial criterion by which a film on such a theme can be judged – whether it comes close to that "rigor strengthened by respect and reverence and, above all, faithfulness to memory" of which Elie Wiesel has written – remains with the viewer. By any standards, however, Distant Journey, is a major achievement, making its return to circulation in this Second Run release, taken from a 2019 4K restoration that brings out the crazed darkness of the Terezin scenes, welcome indeed.

Add comment