There are many outstanding things in writer-director Francis Lee’s remarkable first feature, and prime among them is the sense that nature herself has a distinct presence in the story. It brings home how rarely we see life on the land depicted in British cinema with any credibility. God's Own Country is a gloriously naturalistic depiction of the harsh life of farming, of an existence based on close connection to animals and to the earth, set in the Yorkshire countryside in which the director grew up. For a comparable sense of connection to the rural environment, and of the sheer back-breaking work that comes with that link, we have to look elsewhere – to Zola perhaps, or Italian neorealism.

Closer to home there’s much in God's Own Country that resonates with DH Lawrence, his sense of the primal rhythms of life and death, and the way in which the emotions of these working lives are often expressed with a minimum of language. Lawrence has a poem titled “Love on the Farm”, which could work as an alternative title for Lee’s film – except that love is as far from the mind of its main character, twentysomething Johnny Saxby (played by Josh O'Connor), when we first encounter him as anything could be. In an early scene his grandmother catches his character perfectly when she calls him a “mardy arse”, local vernacular for his being moodily withdrawn (it was a nickname that Lawrence was called at school).

The sense of change feels somehow primal

It’s a world in which communication, particularly within the family, is virtually monosyllabic: the first words we hear Johnny speak, some minutes into the film, he addresses to a heifer, and he’s just had his hand inside her to check on her calf (we see a lot of hands exploring animals’ orifices in God's Own Country: Lee made his actors learn such tasks for themselves, no hand doubles here). With his father Martin (Ian Hart) in poor health, Johnny carries the responsibility for the farm on his shoulders, and there’s little else in his life to give it meaning. The fact that he’s gay isn’t an issue in itself – though it’s not spoken of at home – but sex has the same purely physical dimension as the drink he stupefies himself with at the pub every night. When he takes a cow to market, he has a cold fuck with a man who’s obviously an acquaintance, but the idea of continuing any human contact after the act is completed is alien to him.

Johnny’s world is a lonely one: his mother disappeared south at some stage in the past, unable to deal with the isolation and hardship of the farm. Grandmother Deidre (Gemma Jones, playing well beyond her accustomed range) has a sort of scolding affection for him, but she’s more than reserved with her emotions. A childhood friend has come back home for her university holidays – she notices how Johnny has changed, no longer “funny, like you used to be” – and suggests they have a night out in Bradford. When Johnny mentions the idea to his dad, the latter looks at him like he was talking about the moon. All of which makes the arrival of an outsider an unwelcome disruption. Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) has come from Romania to help for a few weeks with the lambing – he was the only applicant for the job – and Johnny’s hostility is immediate as he taunts him as a “gyppo”. They are going up to the higher pastures for the lambing, to sleep in a ruined hut and subsist, it seems, entirely on pot noodles. Then up there, when least expected, fate stumbles in: in this stark isolation the hostility between the two men turns into something else, Johnny’s anger giving way to tussling, and that into physical contact. At first they fight in the mud, rutting like animals, before a deeper contact slowly grows between them. They may still guy one another, but their words – “freak”, “faggot” – are no longer insults, rather signifiers of an new, joshing intimacy.

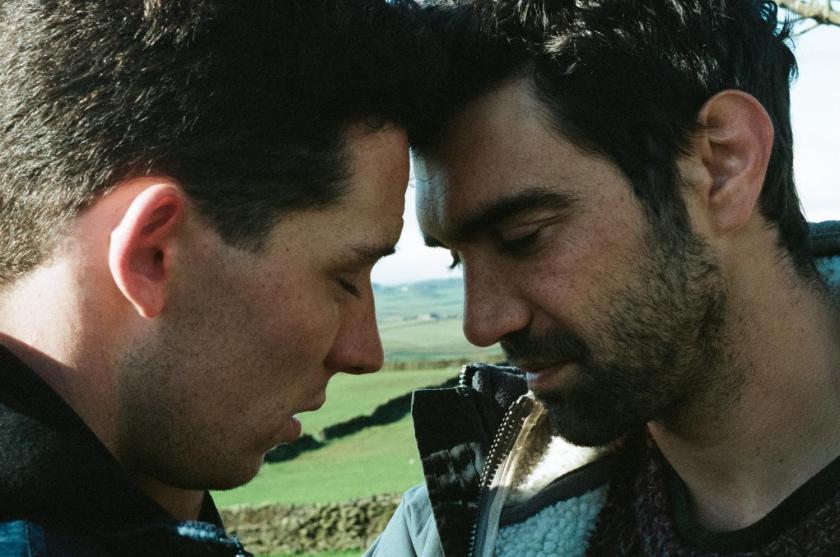

All of which makes the arrival of an outsider an unwelcome disruption. Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) has come from Romania to help for a few weeks with the lambing – he was the only applicant for the job – and Johnny’s hostility is immediate as he taunts him as a “gyppo”. They are going up to the higher pastures for the lambing, to sleep in a ruined hut and subsist, it seems, entirely on pot noodles. Then up there, when least expected, fate stumbles in: in this stark isolation the hostility between the two men turns into something else, Johnny’s anger giving way to tussling, and that into physical contact. At first they fight in the mud, rutting like animals, before a deeper contact slowly grows between them. They may still guy one another, but their words – “freak”, “faggot” – are no longer insults, rather signifiers of an new, joshing intimacy.

Lee convinces us of this changing dynamic with absolute filmic subtlety. There’s a sense that the bleak beauty of their surroundings, to which Gheorghe is receptive, has started to infect Johnny too, as does the sheer gentleness of the outsider. We see the Romanian bring the runt of a litter back to life and then, in a truly beautiful scene, coat it in the pelt of a dead lamb so that the mother sheep will allow it to suckle. All of this is conveyed with such tenderness, expressed far more through images than in the very spare words of Lee’s script (his minimal use of music, principally tracks by A Winged Victory for the Sullen, is also all the more powerful for its sparseness). The sense of change feels somehow primal: simply, the two men come down from the hills different people. Johnny has started to feel things that he never knew he could, while for Gheorghe – everything we hear about his back story and homeland is unremittingly pessimistic, “My country is dead” – the possibility of settling, rather than wandering may have become real.

All of this is conveyed with such tenderness, expressed far more through images than in the very spare words of Lee’s script (his minimal use of music, principally tracks by A Winged Victory for the Sullen, is also all the more powerful for its sparseness). The sense of change feels somehow primal: simply, the two men come down from the hills different people. Johnny has started to feel things that he never knew he could, while for Gheorghe – everything we hear about his back story and homeland is unremittingly pessimistic, “My country is dead” – the possibility of settling, rather than wandering may have become real.

For these two who have felt so out of place in their different worlds, the chance to create a home has suddenly appeared, but Lee’s closing reel will test everything. Johnny, although capable of being surprised by joy, remains his own worst enemy: Josh O'Connor’s face has a remarkable, somehow lopsided vulnerability that conveys all that, and more. In these troubled days of Brexit, it’s salutary to find an outsider portrayed with such total respect. However he may have acquired it – most likely, we guess, though the school of hard knocks – Gheorghe has a self-awareness, and a self-sufficiency, that is both beyond his own years, and aeons beyond Johnny's.

Cinematographer Joshua James Richards portrays these landscapes, these faces with a subtle, surprise beauty that matches Lee’s pacing of his emotional narrative. It’s somehow cyclical, how from the barren earth of winter a new harvest will come forth; over the film’s closing credits we see just that, home-movie archive scenes of harvests past. There’s no praising God's Own Country too highly. Francis Lee may have come out of nowhere, but if we see another film as good this year, we will be lucky.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for God's Own Country

Add comment