Over here we had our own obscenity trial in 1960. Before Lady Chatterley’s Lover made it into the dock, it’s always said that sex in the UK didn’t exist while no sooner had the judge pronounced it not guilty of obscenity than everyone was at it very promptly. Thus does the collective memory simplify. As is usually the case, America got there first. Literature of a provocative nature was put on trial when in 1957 Allen Ginsberg’s priapic epic Howl found itself up before the beak.

The difference between the Chatterley trial and Howl’s day in court are instructive, the former being at least partly about class. As uttered by the prosecuting counsel, “Is it a book that you would even wish your wife or your servants to read?" is arguably as famous a phrase as any DH Lawrence ever wrote. The Howl trial was not about society defending ingrained hierarchies of class or gender; it wasn’t even about libertinism. When everything is stripped away, Ginsberg’s publisher was facing jail for publishing a book that promoted homosexuality to the hilt.

The Howl trial has now been dramatised, but not simply in the form of a courtroom drama. Where Andrew Davies’s The Chatterley Trial (2007) came at the narrative from a fictional angle, telling of two jurors who fall for each other under the influence of Lawrence’s sexually charged prose, Howl is based on transcripts, not only of the trial but of Ginsberg’s retrospective interviews. Thus the action commutes between the court, which can always be relied upon to deliver dramatic tension, and the more contemplative world of the poet’s private sphere.

Meanwhile, there are black and white re-enactments of Ginsberg reciting Howl to a roomful of his Beat Generation pals Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady and their mostly bespectacled young acolytes, who hang on his every word. And as he speaks the film flies off into animations which ecstatically envision his free-associating imagery. These have something of the sultry feel of last year's Cuban musical cartoon Chico and Rita, but where eroticism was there implied in swivelling hips, here swelling phalluses are encouraged to spurt showers of joyous seed.

Meanwhile, there are black and white re-enactments of Ginsberg reciting Howl to a roomful of his Beat Generation pals Jack Kerouac and Neal Cassady and their mostly bespectacled young acolytes, who hang on his every word. And as he speaks the film flies off into animations which ecstatically envision his free-associating imagery. These have something of the sultry feel of last year's Cuban musical cartoon Chico and Rita, but where eroticism was there implied in swivelling hips, here swelling phalluses are encouraged to spurt showers of joyous seed.

But this is more than a cock and balls story. As the young Ginsberg, from the period of his life before he lost his hair and grew a thick beard, James Franco gives a hypnotic performance, ecstatically performing the poetry in public. “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness,” he declaims, and it’s possible to imagine how enrapturing his druggy, jazz-inflected riffing on sex and the bomb must have been in 1955. Meanwhile, in interviews, he delivers a careful facsimile of the poet’s mannered speech, all reflective elongations and self-admiring effect. “The poem,” he concludes, “is misinterpreted as the promotion of homosexuality. Actually it’s a promotion of frankness.”

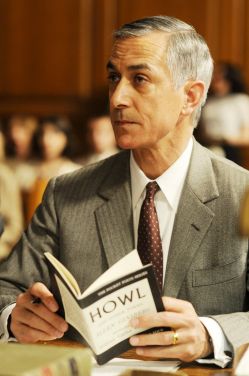

Ginsberg isn’t there for the courtroom drama. As the prosecuting attorney, David Strathairn (pictured above) carefully embodies the upright all-American moral prudery of the Fifties. To a series of witnesses played by Jeff Daniels, Mary-Louise Parker and Alessandro Nivola, he investigates the illicit intentions behind verbs like “snatch” and “blew” and poses casuistical questions about what fundamentally constitutes literary value. It gives nothing away to report that at the close, the judge (played by Bob Balaban) concludes that “an author should be allowed to express his ideas and thoughts in his own words”, and therefore that “Howl does have some redeeming social importance”.

Whether Howl has redeeming importance as a film is another matter. The weave of styles and tones is nicely managed by writers and directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman, while the nuanced performances steer clear of pantomime. But in the end, although the film frigs itself towards some kind of dramatic climax, its value is largely as a historical document. Fans of Ginsberg’s will of course love it. But while he won an important victory against the forces of darkness, how many of those fans are around these days?

Watch the trailer for Howl

Add comment