The second thing I noticed about Miloš Forman, who has died at the age of 86, was the spectacular imperfection of his English. All those decades in America could not muffle his foghorn of a Bohemian accent, nor assimilate the refugees from Czech syntax. The first thing was the heavy Cuban perfume that announced his proximity. It's a wonder America, almost as Stalinist about public smoking as his native Czechoslovakia once was about public speaking, never booted him out.

He torched another reeking missile as he told of an English friend visiting New York "who hadn't been for several years, and said, `It's amazing, there are prostitutes everywhere.' Suddenly he realised. Because today a lot lot of office buildings are smoke-free, so what the secretaries are doing, every time there's a lunch break or coffee break they go down, light their cigarettes and walk leisurely on the sidewalk. So funny."

Forman, born in 1932, grew up in the shadow cast by Nazism, which claimed the lives of both his parents, then found life equally circumscribed by communism. And yet his own career under communism was actually not a minefield of censorship and obstruction. For all the privations he underwent in a nomadic childhood (which would have made a marvellous movie), he was born at precisely the right time to capitalise on the more relaxed atmosphere which prevailed in 1960s Czechoslovakia.

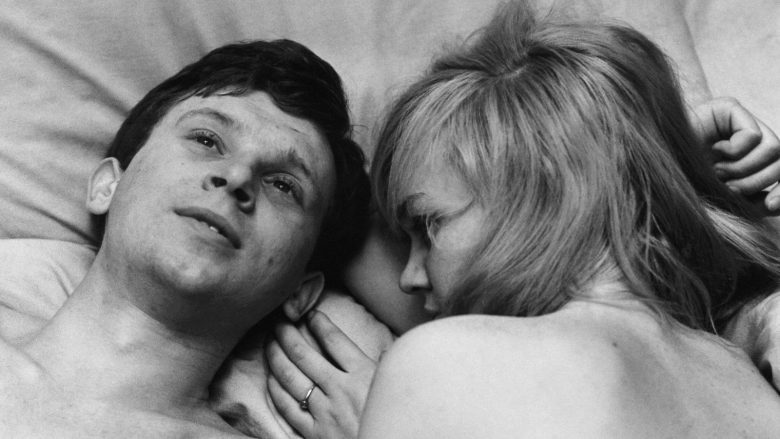

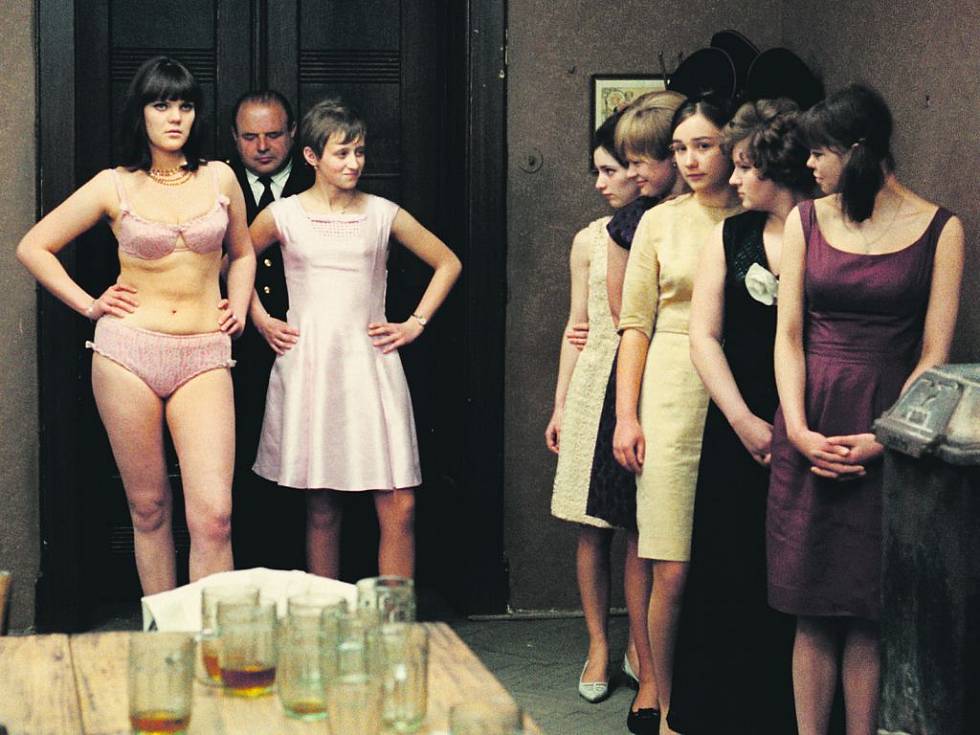

The films he shot there made much use of amateur actors and improvised dialogue. All of them in different ways positioned the protagonists against authority. Audition (1962) was about a shop girl who flunks an audition and a rock singer who misses it. Black Peter (1963) told of an apprentice grocer refusing to inform on an old woman who shoplifts. His first international hit was Loves of a Blonde (1964, pictured below) in which a girl meets a pianist at a welcoming dance for a garrison stationed in a factory town. In a trip to meet him in Prague she is thwarted by his old parents in her desire to sleep with him, but returns home telling fanciful stories of her fiancé. The Fireman's Ball (1967), Forman's first film in colour, was about a fire department dance where there's a raffle in which all the prizes are stolen. It was banned and released only a few days before the Soviet invasion.

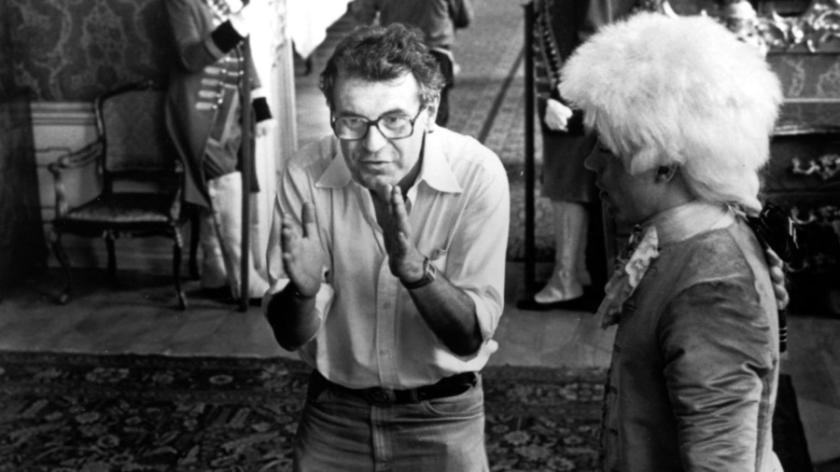

Forman was in France when the Prague Spring was crushed 50 years ago. Leaving a wife and twin sons back in Czechoslovakia, he made his way to the US. Jiří Menzel, the director of the Czechoslovakian Oscar-winner Closely Observed Trains, once said that Forman was the only great European auteur to manage the creative emigration to America on his own terms. It didn’t go well to start with. Taking Off (1971) was not a success, and it wasn’t until One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975) that he had a shot at redemption. It captured every major Oscar, the first film to do so since It Happened One Night in 1934. The theme of the defiant, unjustly victimised outsider continued through Hair (1979), Ragtime (1981) and Amadeus (1984) all the way to The People vs Larry Flynt (1996). His memoir, Turnaround, written with Jan Novak, was published in 1994. He dedicated it “to my parents, all of them”. I interviewed him a few years later, and excerpt this section about his relationship with his homeland. JASPER REES: How much were you personally gagged in the 1960s? In the book it seems that you worked in relative peace.

JASPER REES: How much were you personally gagged in the 1960s? In the book it seems that you worked in relative peace.

MILOŠ FORMAN: That was a lucky coincidence of political events. That was exactly the time after Stalin's death, finally Khrushchev came to power, denounced Stalin and declared in one of his famous speeches, "We have to give more confidence to young people," so the grip of ideological censorship relaxed a little bit and that's when my generation came in. Except that when I finished The Fireman's Ball (pictured below) it was banned officially forever. It was shown briefly, a few days before the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia, then it was banned forever, which in this language means 20 years.

In the memoir you say that the novelist Josef Škvorecký had a tough life. The toughness for you was confined to your childhood. Is that accurate?

It is. As a matter of fact the irony of the situation is that relatively, especially in the Fifties when I was in the film school, Škvorecký was older, he already was, when the communists came, in the productive stage of his life, I was still in the studying stage of my life, and the irony was that nobody could have had more inspiring professors than my generation, because all these great writers and filmmakers from before the communists were suddenly banned and they couldn't work and influence the public with their disruptive decadent morality, so they somehow to let them survive and put them in schools to teach. So suddenly we had professors in film school which normally we would never have had because these people would be too busy with their own careers. These people suddenly are coming. People who are so inspiring. One of them was Milan Kundera. What did you learn from him?

One of them was Milan Kundera. What did you learn from him?

Listen, the most important thing all these people, Kundera especially, is not what technically they teach you, it's what they inspire you. and they inspire you first of all to admire the right things. The literature he was asking us to read was wonderful. The way they talk about literature, movies, history, art was very very inspiring.

He sent you in the direction of Laclos, which led to Valmont, your version of Les Liaisons Dangereuses...

That was one of the books he recommended for us to read. I read it when I was 19 years old. He was a poet and I think he wrote at the time one play, but he was not a novelist. He's a very strange bird. I love him, don't misunderstand me, but he's a strange bird. His fear to let anybody step into his privacy is almost paranoiac, but when you get to know him he's a wonderful guy. For me, when you read his books, it's really on the highest and most exciting intellectual and philosophical level, and when you sit down for dinner you have great fun talking to a Moravian peasant.

Would you have liked to have made The Unbearable Lightness of Being?

I would have at the time, but the problem is, and it's psychological, I could easily make a film about England in Scotland, or about Finland in Spain, but I just can't make a film about Czechoslovakia outside Czechoslovakia, because I would suffer all the time about this house that's not the right architecture, these people don't look like Czech people, Czech people don't wear these clothes.

The other impression from your book is that you do seem to be an upbeat person. You don't tend to look on the downside. Is that a fair impression?

Well, yes, but if you notice there is always tragedy behind the Czech humour, and that goes centuries back, because it's such a small national entity in the middle of Europe surrounded by very powerful neighbours always trying to dominate this little entity, and it’s so small that they couldn't protect themselves with the sword, so it's the survivors' instinct to protect your own sanity with humour. We are the country of The Good Soldier Švejk, Kafka and Čapek. That's the Czech mentality.

Do you still feel yourself to be a Czech artist?

I'll tell you something, it must be, but I really don't like to analyse myself. It doesn't really interest me because I know that I would find satisfactory answers. I would be just torturing myself. The less you know about yourself, the happier you are, believe me.

Yours was the first film in Czechoslovakia to show a naked woman since Hedwig Kiesler (later Hedy Lamarr) in Ecstasy in 1933. What was the reaction to that?

Silence. Nobody mentioned it, nobody attacked it. Silence.

Is that because the Czech mentality is extremely liberal?

Oh yes, deep down, yes. Listen, I was shown when I started to do this film, somebody sent me from Prague etchings from 1870 from Czech publications of that time. I'll tell you, Larry Flynt would blush seeing them. Unbelievable. And you know what's funny? Today these etchings looks really like art.

It's sometimes suggested that your best films were made in your home country. Does that upset you?

No, it doesn't upset me. It doesn't upset me. I understand a certain nostalgia for something and suddenly you are doing something slightly different and you are not the same. No, it was just inevitable. Because, I don't know if you saw some films when the Czechs are trying to make American movies à la Hollywood, or French films à la Hollywood. It's ridiculous, these films. Ridiculous. And the same problem I found out I will have if I try to make Hollywood film à la Czech. You can't do that. You reached a mass international audience with Cuckoo’s Nest (pictured above), but it has a much longer gestation than its fans realise. How did it come about?

You reached a mass international audience with Cuckoo’s Nest (pictured above), but it has a much longer gestation than its fans realise. How did it come about?

It had a very strange story because in 1965 Kirk Douglas was in Prague and mentioned it to me and I never got the book. He never got the message that the censors confiscated it. When I met him years later, he told me, "You son of a bitch, you didn't even answer." And I said, "The same thing I thought about you, you son of a bitch. You promised to send me something and leave the room and forget about it." The censors confiscated it and didn't bother to inform him or me about it.

Which of your Hollywood films is the most Czech?

I tried to make the same way I was working in Czechoslovakia my first film in the US, Taking Off. And that was a lesson, because it flopped totally at the box office. They even didn't put it on video. So that was a lesson.

If it said on your gravestone, "Here lies Milos Forman, he made this film", which would you like that film to be? Amadeus? That's the film that combines the two halves of you.

That was for me emotionally the most provocative and rich experience to go back to for the first time. That's such a sort of glamorously sounding question, to be very smart and say something deep. I really don't know. I don't know. Probably, but it would sound pretentious if I said that. Mozart doesn't even have a grave.

Miloš Forman, 1932-2018

Add comment