As everyone knows, the two most likeable creatures in the fictional world are the dog and the robot. Who doesn’t love a waggly tail or an aluminium cranium? So putting the two together in an animated movie looks like a Bennifer-perfect match.

Robot Dreams pairs them, hand in hand, for walks in the park and rides on the subway in a bright, peppy feature that combines American optimism with mounting European angst. The film by Pablo Berger is a Spanish-French production based on a graphic novel by the American illustrator Sara Varon, and is set in a faithfully drawn New York of the 1980s, full of nods to MTV, cans of Tab, the Weekly World News and Earth, Wind & Fire music – though Madonna songs were presumably beyond the finance of the busy but modestly budgeted cartoon.

A grey globular dog, named Dog, is an obliging type bereft of friends in his East Village apartment (we know he’s male because he eats Cheetos all day in front of the TV, and because he wears trunks at the beach). He orders a self-assembly “Amica 2000” robot, called Robot, to keep himself company; perhaps the “Amica” model is gender-fluid, but the instant love between the two is strictly of the agape rather than eros order, in Ancient Greek terms. (I guess the antagonistic version would have paired a Dog and a Vacuum Cleaner.)

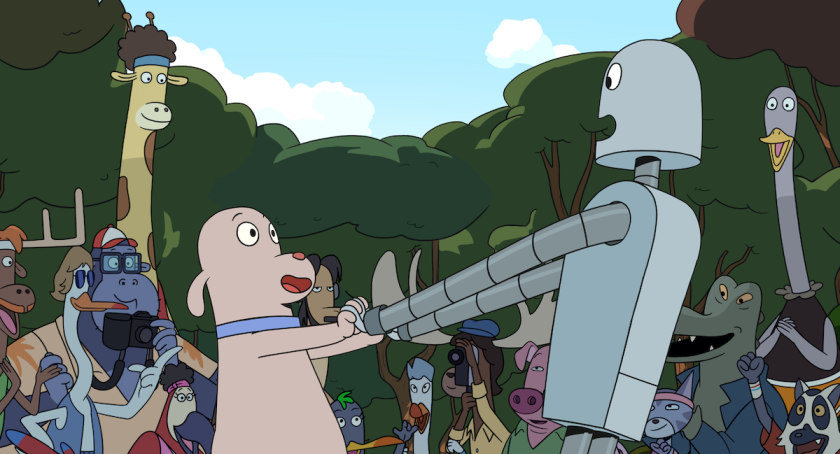

Robot looks strikingly similar to the dissolute Bender from Matt Groening’s Futurama – that is, very stereotypical, though of course the joke in Futurama is precisely that this most adult of androids looks like a regular child’s idea of one.

The meticulously rendered East Village that Dog and Robot inhabit is a charming zootopia of other critters – break-dancing cattle, street-hustling anteaters, toucan cops etc – and their world is entirely bereft of conversation. Folk rely on gestures to get by; they sometimes put in calls on landline phones, but never get through.

Places such as Disney and Pixar sometimes seem half like animation studios, half factories for animal jokes, but the sight gags here are sparingly ladled out. Some of them you might have seen before – like the mouse and the elephant on the boating lake, their vessel near-vertical. Others seem fresher, like the snowman who turns the colour of the Slurpee he’s inhaling, or Dog reading a copy of Stephen King’s Pet Sematary.

The anthropomorphism is restrained, and filmmaker Berger is more interested in what happens when Dog loses Robot. In a rather contrived end-of-first-act, the metal bestie is marooned on a beach after the facility closes for the winter and Dog can’t find a way to reach his mate in the sand.

The two then spend the main part of the film in mutual longing, and in fearing the other’s fear of betrayal. What follows is a series of hallucinations of life regained for Robot, the most elaborate of which – in a film short on set-pieces – is a jaunt on a yellow brick road into a Busby Berkeley throng of dancing daisies. Back in the real world, Dog finds himself a girlfriend of sorts in the form of a duck rather too keen on sporty outdoor pursuits. (It’s not clear if the movie’s mind for puns extends to the British context for Dog and Duck.)

Events lead Robot to a horror space worthy of a Toy Story instalment – a junk yard where dismemberment awaits – and the resolution is not what we (or more particularly our kids) would expect, aiming the film more towards the adult market, or at least the 10-and-upwards crowd. The movie missed out on the 2024 best animation Oscar to Hayao Miyazaki’s dense and gnarly The Boy and the Heron, which was aimed at goodness knows who. Robot Dreams may lack the same visual onslaught but its 2D line-drawing is packed with colour and can-do.

It resolves itself into a story of longing and loneliness done in a breezy manner, and decides that sometimes there’s only one person that’s right for you, and sometimes the yellow brick road leads to somebody else. There’s always another robot in the store. Where a Disney or Pixar version of the story would lead us on some expansive, Homeric journey towards self-actualisation, here we have an introspective tale of yearning for yearning’s sake, a European bridge of sighs that draws on a more recent model of, let’s say, Proust.

Add comment