For a time, Aung San Suu Kyi enjoyed a heroic status on the international stage perhaps surpassed only by Nelson Mandela. The politician won a Nobel peace prize for her non-violent struggle for democracy and human rights in her country, Myanmar (formerly Burma), endured almost 20 years of house arrest, then played a leading role as her country moved towards so-called democracy.

But then her country’s military started a persecution of the minority Rohingya Muslims that quickly became genocide. Aung San Suu Kyi said nothing. And her refusal to condemn the action turned her from hero to villain overnight. The question is, why?

Danish director Karen Stokkendal Poulsen’s new documentary tackles that question by charting Myanmar’s complex transition to democracy after 50 years of military dictatorship, focussing on Aung San Suu Kyi’s pact with the devil – the generals – to ensure she follow her late father’s footsteps and lead the country.

Stokkendal Poulsen has impressive access to these shady corridors of power, including an interview with Aung San Suu Kyi herself and, more revealingly, with the former generals of the dictatorship who craftily segued across to the civilian government.

Alongside the talking heads, she stitches together her own footage from within the Myanmar Parliament with archive from the country’s violent past, including the principal role played by Aung San Suu Kyi’s father, General Aung San, in the battle for independence from the British, before being assassinated by political rivals. Tellingly, Stokkendal Poulsen’s own voice-over narration notes that Aung San left the Burmese people “a military, and a daughter’.

The result is a clear-eyed, succinct, gripping insight into an unusual political phenomenon and an almost Shakespearean personal drama.

The Dane has a political background, having studied political science and worked for a time as a junior diplomat with Denmark’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She’s also lectured in international relations at the University of Copenhagen.

The Dane has a political background, having studied political science and worked for a time as a junior diplomat with Denmark’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. She’s also lectured in international relations at the University of Copenhagen.

In 2008 she graduated with a master’s degree in “screen documentary” from London’s Goldsmiths College. Her first documentary, The Agreement (2014) follows an EU negotiator, the Briton Robert Cooper (pictured above), as he conducts talks between Serbia and Kosovo over territorial disputes. It’s a fly-on-the-wall gem, which turns diplomatic minutiae into riveting comic-drama.

The charismatic Cooper has numerous memorable lines in the film, including the observation that, “History is always made late at night, when everybody is tired and fed up”. The diplomat would also play an instigating role in the film that followed, thousands of miles away from Brussels in southeast Asia.

The Arts Desk met Karen Stokkendal Poulsen when On the Inside of a Military Dictatorship had its world premiere at the CPH:Dox film festival in Copenhagen. As in so many conversations about the troubled country, in what follows 'Myanmar' and 'Burma' become interchangeable.

DEMETRIOS MATHEOU: How did the film come about?

KAREN STOKKENDAL POULSEN: While I was making The Agreement, with Robert Cooper as the main character, he was simultaneously working in Myanmar, where he was sent as a special advisor to negotiate with the military regime about lifting EU sanctions. Aung San Suu Kyi had just been released from house arrest. Robert actually went to Oxford with her and was a pretty close friend.

So while I was shooting in Brussels I would hear these stories. Sometimes when I was with Robert, Aung San Suu Kyi would call. And I was getting curious about this ‘miracle’ over there. Later The Agreement was selected for a human rights festival in Burma. So he proposed I make a film about her presidential campaign, and offered to set up contacts on my behalf.

That's how it started. Then he gave me some of her favourite cheeses from London – so he made sure she’d meet me! That was in 2014.

And how did that first meeting go?

And how did that first meeting go?

She agreed in principle to make a film about herself and the elections. And she was helpful in the sense that I had direct access. But she never seemed to be willing to actually participate. In The Agreement I was inside that process, filming day and night. She would never give me the same access, of being inside those confidential rooms with her.

Later on I think I understood why that was. This is a country that has been a military regime for 50 years. For her it wasn’t just about trusting me, it's about trusting that nobody is able to penetrate my material, for instance. They are very good at surveilling you. Anybody's an informant, you never know. She says it in the film. I know for sure that they had access to my mobile phone.

Did you turn to the generals because Aung San Suu Kyi wasn’t really delivering?

In a way, yes. I also felt that everybody was chasing her, but nobody ever talks to these guys. How do they see her? How do they see democratisation? Suddenly I was super curious to change the perspective and go deeper into what it is like to be on the wrong side of history.

And then I started meeting them and it was so interesting. First of all, I hadn't seen it before myself, nobody had ever filmed them. For some of them it's the first time they’ve talked on camera. You can tell from the way they talk; however much they want to be in control, they are not media trained.

It couldn’t have been straightforward getting access, even though these men were now part of the so-called civilian government.

Again, initially I was helped by Robert Cooper, who put me in touch with a lot of people. And the British Ambassador was very helpful also. They weren't supporting the film, they were just giving me introductions. Initially I got no replies. But then one day in Parliament – I was there every day, filming – the minister for information was there, surrounded by Burmese journalists. I was the only Western person. And he just came up and said ‘Who are you, where are you're from?’ I introduced myself and said we'd already sent him a formal request for an interview. And then he called his office and said, ‘Come tomorrow'.

I had another week left of that visit and so I just stayed with him. I was the first one to meet him in the morning, we were driving him around, to all his meetings and formal activities. And then I went back to Denmark and said, ‘Now I think we have a completely different story’.

And did he connect you to others in the military?

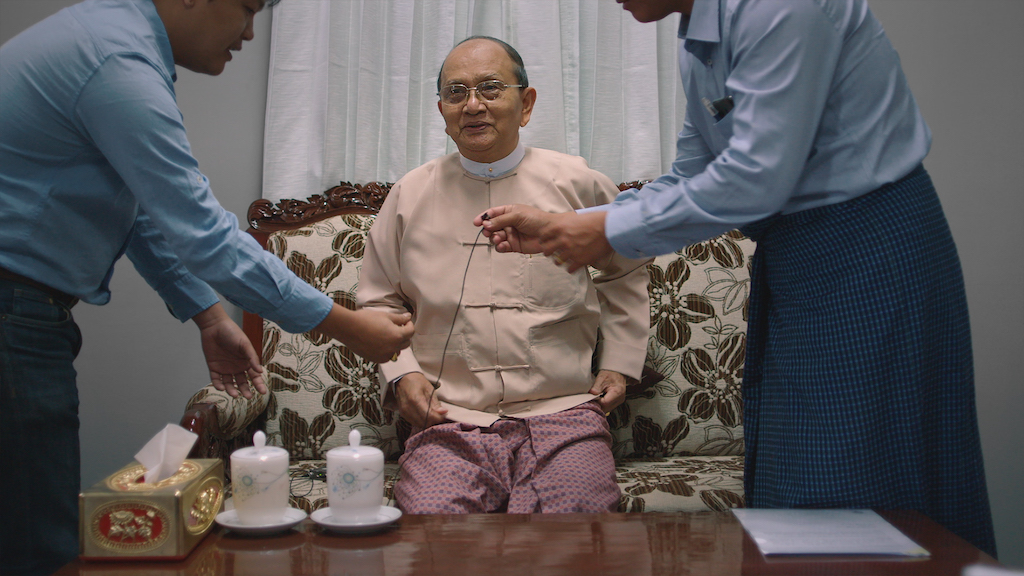

He opened the door to one of them. And then I got some very, very good local associate producers, well-connected journalists, who helped. And when I had an interview with another ex-general, he told his assistants that he liked the project and to contact the president and recommend he participate [President Thein Sein pictured below].

Were the generals you feature involved in the atrocities of the dictatorship?

Were the generals you feature involved in the atrocities of the dictatorship?

Absolutely. The first thing we see [in the film] is 1988 when they shot people down in the streets. These guys all say it was necessary. Then I introduce them as being top of the US targeted sanction list. Every time we talk about what the military did in the past, all those wars, they were leading them. But at this point in time they had stepped down.

Did you feel they believed in the idea of democracy?

I think they were reform friendly. But we should think of them as having grown up in this system, years in the military life, with security as their priority. Then comes this idea of democracy, which they like, but it doesn't change that core.

There’s an interesting contrast between the generals, who are smiling for the camera, and Aung San Suu Kyi, who looks horribly uncomfortable.

My one interview with Aung San Suu Kyi was conducted in 2015, before the general election. She was vey aware of the obstacles ahead. In fact when we first met, I said one of the reasons for making this film was that everybody talked about this miracle in her country and the opportunity now for change and democracy. And she immediately said, ‘This is not a miracle’, then listed every way the generals kept power in their hands.

I think that myself and other western observers jumped into the trap. When the military offered democratisation, we all said ‘fantastic’. But the people inside Myanmar knew it was going to be tough

These same observers now condemn her for having lost her moral compass in the Rohingya crisis. Your film adds a more subtle perspective.

First, I think she was never the saint people thought her to be. I try to show in the film that she's pretty good at playing the strategic game – she's willing to go pretty far to get in power and accomplish her project. There are many things you can criticise Aung San Suu Kyi for, especially the limited press freedom.

But I feel there has been a simplified portrayal of her, people haven't distinguished between her character and the context in which she's operating. She’s trapped. I would think twice about criticising the military or going up against the military if I were her, when you have a lawyer trying to change the law and he's assassinated. It's not a walk in the park to go up against this regime.  The way her character plays a part in her fate is almost Shakespearean.

The way her character plays a part in her fate is almost Shakespearean.

That’s what we said every second day in the editing room. The tragedy of it. Also, a little, our staging of it. International relations are usually covered in current affairs documentaries, news journalism of course, and more analytical research. My ambition was to try to make it cinematic – to go beyond the general drama to the deeper human aspects, the political aspects, which lift it to another level.

I really think that Aung San Suu Kyi believes she was born with a destiny. And the people of Burma believe the same. And then there was her ambiguous relationship with the military – in a way brother and sister, in a way worst enemies. I think she understands the generals’ logic. I remember her stating at one point that people were so critical of her when she didn't compromise, not willing to make any sort of deal, and now they were criticising her for being complicit. This was long before the Rohingya crisis. She made the first comprise, which you see in the film, when she enters Parliament and swears to the constitution. And then the next, and the next.

Is she right to stick to it, just for power? You imply is that she's so fixed on her end game, which is eventually to become president, that she can't pull away.

I think from a moral perspective that she should have stepped down. I think the crisis is so immense that it would have been better to say, ‘I cannot be in government with this military regime’ and speak her mind. It doesn't mean that I don't understand the reasons she didn't.

Did you get any access to her after the crisis?

I didn't. But I interviewed her spokesperson, who’s very close to her, so I felt he was representing her in a way.

Your narration is quite artful, filling in a lot of key historical context and joining the dots.

Some of the elements of this film came almost because of an obstruction, because I had to find another way to communicate something. I was hearing so many things that people didn't dare say on camera. Some of this can be dangerous to say aloud in Myanmar – not for me, but a local. So I decided to step in myself. Actually we had a screening in Myanmar two weeks ago, and there was this young local journalist thanking, thanking, and telling us, ‘You're saying aloud what we cannot say.’

Did you feel in danger there yourself?

No, because I knew that they probably wouldn't touch Westerners. I was sometimes afraid for my local employees – who were setting up interviews, translating things, taking me around – because they could get in trouble. I'd say to them, ’You know much better than me where the limits are, so you have to say if we’re about to cross them.

It feels that European democracy is experiencing its own chaos at the moment. Though your film puts that into a kind of perspective.

It's funny, one of our local associate producers has watched [Danish TV political drama] Borgen. He said it was a nice series, but when he thought about what a Danish prime minister’s dilemmas were – ‘Do I have time to breakfast with my kids!’ Compare that to Aung San Suu Kyi, who has these different ethnic groups, civil war, the military on her back. He's very critical of her and her government, but started to feel she has a lot on her shoulders.

Add comment