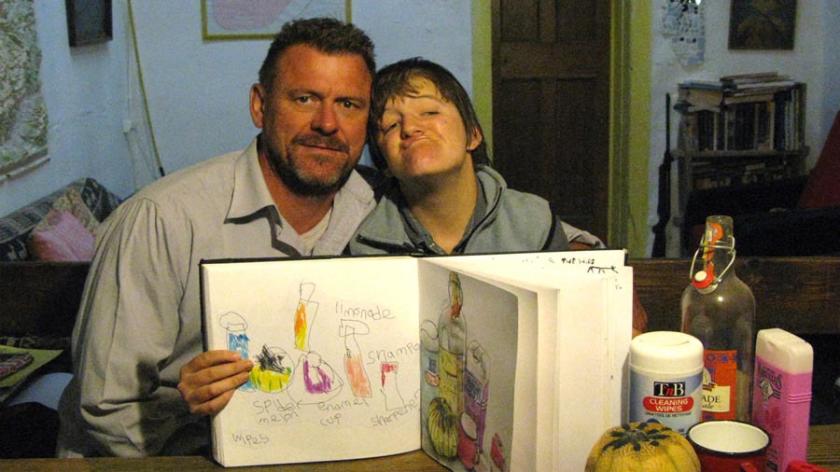

Fifteen years after I first saw Andrew Kötting’s Gallivant (1996), I’m still haunted by its depiction of the pilgrimage Kötting made around the coast of Britain with his 85-year-old grandmother Gladys and his seven-year-old daughter Eden (pictured together below right). Lyrical but not sentimentally scenic, it paid homage to folk customs that contain the spirit of ancient communal life while pointedly spurning the commercial culture that characterises resort towns.

The best-known movie by the film-maker and installation/performance artist Kötting, it was a psychographic fin-de-siècle meditation on the British spirit of place, one tacitly aware of the fragility of two daughters of Albion: a woman coming to the end of her life and a little girl living a precarious existence. Eden suffers from the rare and incurable genetic condition Joubert’s Syndrome, in which the cerebellum is undeveloped, causing problems with speech, motor co-ordination, eye movements and breathing.

A kind of answer to the restlessness of Gallivant, Kötting’s equally mesmerising This Our Still Life (2011), recently released on DVD by the BFI, is a dazzling impressionistic portrait of his family in pastoral retreat in the Pyrenees – and a part-joyful, part-melancholy memory movie that takes its cue from the still lifes painted by Kötting and Eden, who at 22 remains an endearing presence.

Shot at Louyre, the ramshackle mountainside house with a tin bathtub and an invasive snake in a bedroom where Kötting, his wife Leila and Eden spend three months every year, the film is comprised of grainy Super 8 and shimmering digital images. Archival voice recordings and self-consciously declamatory titles enigmatise the raw home-movie footage, which Kötting edited with the ghost of the experimental film-maker Stan Brakhage looking over his shoulder.

Kötting has made more formal movies, including This Filthy Earth (2001), his squalid English deconstruction of Zola's La Terre, and Ivul (2009), a semi-autobiographical account of a dysfunctional Russian émigre family dwelling in the Pyrenees. But his “Eden-ic” films are his most magical.

Kötting has made more formal movies, including This Filthy Earth (2001), his squalid English deconstruction of Zola's La Terre, and Ivul (2009), a semi-autobiographical account of a dysfunctional Russian émigre family dwelling in the Pyrenees. But his “Eden-ic” films are his most magical.

The DVD includes Mapping Perceptions (2002), a conflation of art and science that begins by contrasting Kötting’s brain with Eden’s; An History of Civilisation (2011), a rumination on Southwark Park past, present and future; and artist-film-maker Gideon Koppel’s A Portrait of Eden (2011), one of a series of films about young people with intellectual disabilities intended as an aid for social services. The 52-year-old Kötting, who’s more amiably blokeish than the average avant-garde director, talks to theartsdesk.

GRAHAM FULLER: Did you conceive This Our Still Life with a specific structure, or did it emerge through osmosis?

ANDREW KÖTTING: Instead of osmosis I think I use spillage a lot. One idea flows into another. It’s always very loose and there’s never any kind of particular structure or any great ambition behind it. This film grew out of a love of the part of the Pyrenees where I’ve spent almost 23 years on and off. Eden and I had been doing a series of still-life drawings and the whole thing grew out of my intentions to release a little book work of our art, which had been in various exhibitions. My prose poetry that accompanied the drawings cemented the project. Since we first came to Louyre with Eden, I’d been keeping a kind of diary on Super 8 and then in the last three or four years I used a cheap Samsung digital camera. I thought, why don’t I chuck in a portrait of Louyre (pictured below left) in the book work and incorporate a little film? It was a breath of fresh air having come off Ivul, quite a big feature film I made in France, which had been a real labour of love.

Suddenly I was in the edit suite just mucking about, no pressures whatsoever, and the film eventually worked as a companion piece to Eden’s paintings, my drawings, and the texts that litter it. It’s a kind of funny marriage of the various component parts.

Suddenly I was in the edit suite just mucking about, no pressures whatsoever, and the film eventually worked as a companion piece to Eden’s paintings, my drawings, and the texts that litter it. It’s a kind of funny marriage of the various component parts.

The only structure as such is the seasons. That came about because I was mediating all this footage and discovered these titles at the film archives in Brent, where I was doing research for Ivul. I thought I'd put all the bits that I like from January through January in order and have the titles demarcate the seasons.

I was back in the Pyrenees on my own for 10 days and shot one scene where I go out into the forest. There’s also a bit that’s very dark where I’m wandering around talking about the presences within the house. Strange things happen when I’m there on my own and I tried to capture them.

Is it strange being there without Leila and Eden?

Yes, I’m consumed by melancholia, nostalgia and loneliness. The sense of the hermetic and solitude is palpable. I dwell upon mortality and, paradoxically, it really makes you feel alive. And I love the sense of being at one remove from civilisation and the rest of the world. Because the house is so pregnant with trace elements of our lives there, the film is like an autopsy in a way. It’s me looking in detail at everything that’s in that place. For me, the objects there are mnemonics, or triggers, that remind me of good times, bad times, other people that have visited, all the things that have gone on.

As the film came together, did you intellectualise it in terms of framing memories, capturing what’s transient, the passage of time, or is the editing process less cerebral than that?

It’s very intuitive. My gut feeling is the motor. The film is full of non sequiturs and a sort of yearning or homage to the notions of existentialism. It’s more cerebral when I need to make some sense of the text and the voices and start to finesse it. You know it’s right when you’ve found the right soundbite or you’ve removed the right words from a sentence.

The voice recordings that pepper the film mostly sound as if they come from the Fifties and some have that upper-middle-class BBC tone. Their formal quality contrasts with the rawness and randomness of the images. Was that your intention?

Yes. I like those ruptures and disjunctions. But I think there’s a kind of matter in those voices. They’re certainly inscribed in my past, when we’d have 16mm public information films shown at Easter and at Christmas as a school treat. There’s a kind of gravitas to those experiences and those memories, and as soon as you start working with the material, it feels potent. It’s both at odds and at the same time in keeping with the rawness of the images, because it all feels archival.

Obviously, there’s a dual idea of still life: one, the still lifes that you and Eden paint; two, the comparative stasis of your life at Louyre. It contrasts with the constant movement of Gallivant.

As a title, This Our Still Life is slightly ironic and paradoxical because our lives down there are very different to the frenetic existence of living in the big city. Louyre was always an antidote to London. I don’t know if there’s something about the freneticity in Gallivant that was needed, because that whole film was a lot more bizarre than I think this is. The stillness that comes through the mountainous, isolated life we have in the Pyrenees encourages everything.

I have an abundance of nervous energy and I’m always on the go, but down there things stop and life is more about digging holes for shit in the ground, sawing wood, pumping water and mending the gutters. Everything’s more stolid and plodding. Then, as you say, there’s the more formalistic thing of the still lifes that Eden and I do, which is a convention that’s been handed down from the 16th century. You put objects on a table, look at them, and draw them. The translation into French is nature morte, as in dead life, and that’s another paradox that I love – the idea of them being dead as opposed to being alive.

The moving image doesn’t mean much to Eden unless she’s in it – maybe it’s vainglory

What does being filmed mean to Eden?

There’s one quite important scene in the film, filmed in black and white on Super 8, where she’s sitting with headphones listening to DAT recordings. Eden likes nothing better than to listen to herself or to watch herself, and it gives Leila and myself respite at the end of the day. So quite often I put a camera on a tripod and film us messing around in the studio or cooking breakfast or clearing up the plates, and she likes to sit and look and listen to that on my computer or her computer. It buys us some reading time so it’s a functional tool. At the same time, she’s very keen to be documented. The moving image doesn’t mean much to her unless she’s in it – maybe it’s vainglory. She falls asleep watching pretty much every film apart from Gallivant and Mapping Perceptions. Anything she’s in, she’ll sit there glued to it. It’s the same with music. She plays a lot of music with me now, drums and stuff, and she’ll sit and listen to herself but she’s not that interested unless somehow she’s involved.

The digital camerawork has a kind of fragile, impressionistic quality. Is that a style choice or a simple function of the camera?

It’s simply the camera, but when I put the footage on the computer I was seduced by the pointillistic nature of the image-making. There’s something about the pixillations that are at odds with the grainy quality of Super 8 and makes the images more painterly. I remember for Eden’s benefit, quite early on, I shot some stuff of her cooking and banged it into the video projector, and I thought, God, there’s something beautiful and lush about these dots of colour that make up an image. I said, “OK, it’s lo-fi, but who gives a fuck? It’s absolutely gorgeous.” Then, of course, when you sculpt with sound, as I do, there’s this weird spell you fall into: you’ve got something rough and knackered and pointillistic happening as an image stream, and then you’ve got clean sound, which is the glue because it feels real. Another bedrock is the sound archives, from which these voices come at you.

I’ve read reviews of the film that said the titles you use are portentous. One critic who used that word meant it negatively, another positively. I see them as satirical slogans.

I use them as aphorisms. It’s a bit of a piss-take on the pretentiousness of art-making and of sitting in a room with the lights off for 60 minutes looking at some home-movie footage, with disparate noises coming at you, pretending to be art and really it’s all bollocks. I’m aware of the fact that that’s how a lot of people will always regard… not just what I do, but the pretentiousness of poetry, the audacity of putting oneself or one’s art or one’s existence onto any kind of pedestal and sending it out into the world. Those sensors in my head are always going, “What the fuck are you doing?” And so some of the portentousness is responding to that and putting it on the screen as bait. I’m partially baiting my alter ego.

When I put these titles into uppercase, it’s almost as if I’m shouting these things at the audience. There’s one bit where I go on about religion so often disappointing its customers, and that’s because I thought you could misread the film as a slightly Christian piece, as Seventh-Day Adventist propaganda, and I didn’t want that, because if anything it’s a slightly anti-religious piece. It’s about spirituality, animism, othernesses in the landscape, the presences in one’s head – it’s about us being flesh radios receptive to the stuff that comes in and out, sometimes with voices. That also connects with Eden and the notion that she’s like a Greek siren in the film. The things that move through her move through me and move through the landscape, and come back at you. Occasionally, though, I think the titles are little guy-ropes that peg the film down briefly before the images and the ideas move on to something else.

You don’t put barriers between what you’re shooting and what we see. Your films have elements of style, but they’re not what I’d call stylised. Is that because you think style is untruthful?

It’s more that I’m drawn to the idea of bricolage. Directors whose work I love – Tarkovsky, Béla Tarr, Lars von Trier – use particular kinds of mises-en-scène to deliver their stories. But I’m not that interested. I just like chucking ideas at the medium and making it work. Maybe it comes from Joseph Beuys or Kurt Schwitters, maybe even Samuel Beckett. There’s all kinds of things happening at the same time, and I think that’s what most of the work is about, even if I’m trying to tell a story. I like subverting narrativity, or tripping it up or juggling it and glueing it to the magically real. If I have any kind of style then I try very hard not to keep doing it, but it always comes back and makes me do it.

Do you ever see yourself making a more conventional kind of film?

There’s a bit of me that would like to, and I guess in my head I thought I was working towards that. But I couldn’t do it. I’m too restless and too disinterested. I might be able to do it if I was on smack and could drift in and out of consciousness on and off the set and was surrounded by the apparatus of proper film-making. There’s a possibility I might be able to get something sorted, but I suspect not. It’s hard enough to make work at the best of times, and the idea of committing two or three years of one’s life to somebody else’s writing… I couldn’t do it. Everything I’ve ever done I’ve done because I can’t not do it.

Add comment