Fantômas was the creation of French pulp novelists Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, whose titular criminal genius made his first print appearance in 1911. An amoral sadist with a talent for disguise, Fantômas made his first film appearance two years later in a five-episode crime serial directed by Louis Feuillade. Feuillade’s sober, stripped-back adaptation was hugely influential and the template for subsequent attempts to put Fantômas on screen. Until the mid-1960s, that is, when André Hunebelle helmed three brightly coloured Fantômas romps which so enraged co-creator Allain that he threatened legal action against Gaumont studios.

The trilogy has been described as a Gallic response to the James Bond franchise, though Blake Edwards’ The Pink Panther and A Shot in the Dark have more similarities. Particularly in Hunebelle’s casting of comic actor Louis de Funès as Commissaire Juve, a Clouseau-like detective who persistently fails to nail his quarry. Jean Marais appears in a dual role as both Fantômas and the journalist Fandor. Marais’ expressive face and eyes were his greatest assets, and having him wear a rigid blue mask, his voice dubbed by an uncredited Raymond Pellegrin, feels perverse.

But, by all accounts, Marais initially enjoyed himself, climbing up cranes, dangling from rope ladders and running on top of speeding trains with aplomb, Fantômas’s habit of donning realistic rubber face masks to disguise himself adding to the Mission: Impossible vibes. 1964’s Fantômas is the best of the trilogy. Filmed mostly on location in Paris, Marais is visibly enjoying playing Fandor as an action hero and a luminous Mylène Demongeot is his feisty love interest.

The sequel, 1965’s Fantômas se déchaîne, opens with Juve being awarded the Légion d’Honneur for his work in defeating Fantômas. Glossier, noisier and frequently incoherent, the Bond influences are overt. A groovy secret lair (complete with shark tank) “built on the slopes of a submerged volcano”, predates Blofeld’s hideout in You Only Live Twice, with Fantômas hijacking a police broadcast to announce his plan to deploy “a ghastly weapon” and rule the world. Juve’s response is to use gadgetry to save the day, with mechanical arms and exploding cigars playing a significant part. De Funès’s hyperactive schtick hasn’t worn well, though his performance as Juve was key to the film’s popularity. Stay watching til the end, though, when Fantômas evades capture by having his white Citroën DS sprout retractable wings and take off.

Fantômas contre Scotland Yard followed in 1967. Scotland Yard doesn’t feature, though the action unfolds in a supposedly Scottish castle that resembles a French chateau. Screenwriter Jean Alain announced to the press that “we will go back to the original Fantômas, that of the novels by Marcel Allain, and will renounce the spirit of James Bond.” Hunebelle wasn’t convinced, not wanting to alienate family audiences. The film’s central conceit is a good one, Fantômas threatening the world’s super-rich into paying their fair share of taxes – to him, of course (“in this fine society, crooks and the privileged are one and the same…”). We get more scenes with a frantically mugging de Funès, by now established as one of France’s most popular comic actors. His fame allowed him to negotiate a higher salary, much to Marais’s chagrin, the relationship between the two actors under severe strain. Demongeot is given more to do than in the previous two instalments, but Marais looks tired and disinterested, the film’s nonsensical conclusion coming as a blessed relief. A planned fourth episode, Fantômas à Moscou, went into pre-production but was quietly dropped, the character later resurfacing in a 1980 television adaptation co-directed by Claude Chabrol.

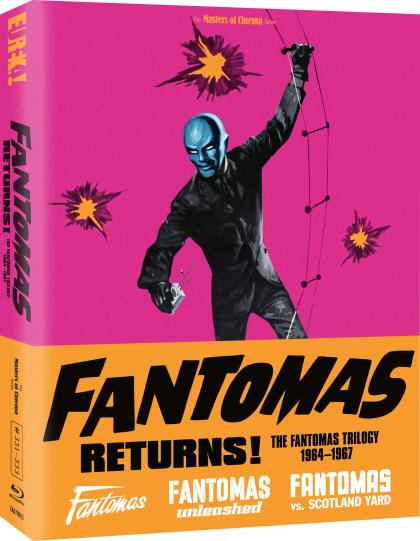

These aren’t masterpieces, then, but Eureka’s production values bump this release up to a four-star rating. Image and sound are vivid and clear, the set’s bonus features including commentaries and documentary material. Leon Hunt’s discussion of 1960s International Supercrooks is fun, and Mary Harrod examines the improbably successful career of Louis de Funès. A 60-page booklet is an entertaining and enjoyable read. One for the curious.

Add comment