Breathing through an oxygen mask with a busted diaphragm and rib after shooting a single scene in mother!, Jennifer Lawrence had rarely suffered more for her art. Nor have we.

The charm quickly palls in Victoria and Abdul, a watery sequel of sorts to Mrs Brown that salvages what lustre it can from its octogenarian star, the indefatigable Judi Dench. Illuminating a little-known friendship between Queen Victoria in her waning years and the Indian servant, Abdul Karim (Ali Fazal), whom she invited into her inner sanctum, the busy Stephen Frears and his screenwriter Lee Hall could use considerably more of the incisiveness and wit that made Frears's similarly royalty-minded The Queen soar.

Instead, we get a characteristically deft character portrait from Dench, marked out by an utter lack of vanity, that is compromised by the faintly risible approach of a screenplay that treads with a heavy step indeed.

Is it because the movie has an understandable eye on the overseas market that the Brits on view all wander about saying "top hole" and "bloody hell" at every opportunity, even as Karim is given a sidekick (Adeel Akhtar) whose attempted levity mostly makes one cringe? (At least Akhtar's ever-sceptical Mohammed knows a good mango when he sees one.) Few would dispute the plea for tolerance and acceptance implicit in every frame – a monarch befriending a Muslim: imagine! – but greater rigour all round might have added a spine which Dench alone supplies. Britain's most beloved senior actress became a movie star, of course, on the back of Mrs Brown, which launched an Oscar-friendly film career. This Victoria redux finds the queen older and starchier and in need of the easy warmth and amity proffered by Abdul, a 24-year-old (and married) clerk who in 1887 gets dispatched from Agra to Britain to present Victoria with a newly-minuted mohur, or ceremonial gold coin.

Britain's most beloved senior actress became a movie star, of course, on the back of Mrs Brown, which launched an Oscar-friendly film career. This Victoria redux finds the queen older and starchier and in need of the easy warmth and amity proffered by Abdul, a 24-year-old (and married) clerk who in 1887 gets dispatched from Agra to Britain to present Victoria with a newly-minuted mohur, or ceremonial gold coin.

The two lock eyes at a formal banquet and something is kickstarted deep within the heavily cloaked royal, who is given lines like "we're all prisoners, Mr Karim", lest we fail to appreciate that presiding over an empire isn't necessarily great fun. So while her family and retinue bitch and moan about how this isn't the done thing (Olivia Williams's Baroness Churchill dismisses Abdul as "the brown John Brown"), Victoria makes of Abdul her munshi, or secretary-cum-teacher. Before you know it, the two are walking arm-in-arm and old Vic is proving a dab hand at Urdu, leaving her son and heir, Bertie (Eddie Izzard, pictured above), to furrow his brow with such intensity that you wonder whether Izzard's face might seize up altogether.

One senses beneath it all the rebuke to Brexit-era Britain that courses through the depiction here of high society at its most straitened and blinkered, Victoria an expansive-looking visionary engulfed at home by bigots. As anticipated, Dench does brilliantly by her big set piece late-on, in which she defends her sanity while cataloguing the various other qualities and infirmities that she may or may not possess. (Were this a play, the moment would generate spontaneous applause.) Elsewhere, the movie seems determined to be a sort of de facto "This is Your Life" for its star, who gets to revisit not just the queens she has assayed over time, Elizabeth 1 and Cleopatra included, but is given a jolly Room with a View-style jaunt to Florence. While there, she and Abdul encounter Simon Callow, no less, having a high old time as Puccini, and Dame J does her best to trill a phrase or two from Gilbert & Sullivan.

Elsewhere, the movie seems determined to be a sort of de facto "This is Your Life" for its star, who gets to revisit not just the queens she has assayed over time, Elizabeth 1 and Cleopatra included, but is given a jolly Room with a View-style jaunt to Florence. While there, she and Abdul encounter Simon Callow, no less, having a high old time as Puccini, and Dame J does her best to trill a phrase or two from Gilbert & Sullivan.

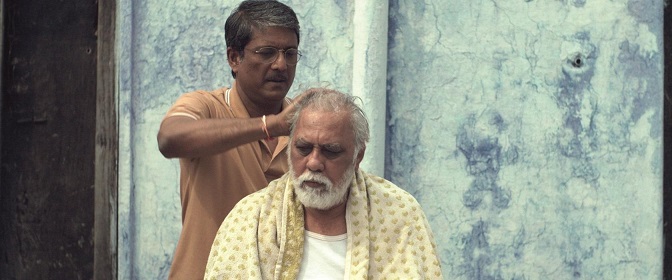

In casting terms, no one besides Dench gets much of a look-in, the sweet-faced Fazal, a Bollywood star at home, functioning mainly as an enabler for his senior colleague and not much else. The English supporting cast includes such notables as Michael Gambon, whom it is always nice to see onscreen given that he no longer works on stage, playing a tetchy Prime Minister, not to mention the late and much-missed Tim Pigott-Smith as Henry Ponsonby, the queen's private secretary (the two men pictured above). But the movie such as it is belongs to Dench, who at this point in her storied career deserves better, and when Frears's camera homes in on the queen breathing her last, one is reminded anew of the gifts of an actress whose talent, happily, remains timeless.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Victoria and Abdul

It doesn’t take long, I think, to work out the associations of the title of Insyriated: we are surely being presented with a variation of “incarceration”, one tinged by the very specific context of the conflict that has ravaged Syria for six years now. But there’s a certain ambiguity at the centre of Belgian director Philippe Van Leeuw’s film about a Damascus family confined in their apartment as civil war goes on around them – they have not been literally locked up by anyone, rather their temporary self-confinement, presided over and enforced by the powerful matriarch Oum Yazan (Hiam Abbass), is their best, perhaps only chance of survival.

It forces us to appreciate a situation tragically played out in the Syrian conflict, although it could equally well apply to any such war zone. Outside is a place of peril, a courtyard where any movement can be caught by snipers. Inside, the curtains are drawn, the door is heavily bolted, and at moments of bombardment – or any other physical encroachment – the only retreat is a corner of the kitchen, away from windows, behind yet more locks (the family hiding-place, pictured below). In between sporadic moments of drama, the challenge is to maintain an illusion, any illusion of normality, simply to carry on living.

Then the violence of the outside world suddenly intrudes

Though claustrophobia is certainly an element, what Insyriated captures best are the long pauses, the moments of protracted limbo that come between the film’s eruptions of action. Van Leeuw opens his film – and closes it, too – with the image of an old man smoking, complete with a tranquillity that seems almost outside time. In the early morning light Virginie Surdej’s camera pans slowly around the spacious room in which he sits, revealing pictures on the walls and long shelves of books: this is clearly the home of a family from the intelligentsia. In a bedroom, a young couple are discussing their chance of escape, how they can travel to Beirut that night. For their baby child, Halima (Diamand Abou Abboud) knows that it is an opportunity that must be risked, even as her husband Samir admits that leaving his homeland makes him feel, in the most curious way, ashamed.

Then the violence of the outside world suddenly intrudes. On his way to sort out some last things before their departure, Samir sprints across the courtyard, but is caught by a sniper’s bullet; his body thrown behind a burnt-out car, it’s unclear whether he’s alive or dead. Delhani (Juliette Navis), the family maid, witnesses the shooting, and hurries to tell Oum Yazan. Any attempt to retrieve the body impossible during daylight, the latter resolves to keep the news from Halima, a decision that will later create incremental conflict. As the day starts, the rest of the family – two daughters, Yara and Aliya, and son Yazan – appears and interrelationships become clear. Halima and Samir are actually neighbours: their upstairs apartment damaged, they have been welcomed into this home. Another visitor is Kareem, Yara’s boyfriend, who had unwisely come to visit her and is now unable to return home until the situation outside calms down. The old man is Oum Yazan’s father-in-law Mustafa (Mohsen Abbas); her husband is expected back, but attempts to make contact with him prove fruitless.

As the day starts, the rest of the family – two daughters, Yara and Aliya, and son Yazan – appears and interrelationships become clear. Halima and Samir are actually neighbours: their upstairs apartment damaged, they have been welcomed into this home. Another visitor is Kareem, Yara’s boyfriend, who had unwisely come to visit her and is now unable to return home until the situation outside calms down. The old man is Oum Yazan’s father-in-law Mustafa (Mohsen Abbas); her husband is expected back, but attempts to make contact with him prove fruitless.

The film is carried by the sheer force of Abbass’s performance, the haggard strength of her face revealing an unspoken conviction that life must be kept going somehow, even as it barely conceals the turmoil behind her features. Explosions outside are followed, only moments later, by her insistent phrases of reaction – “Now, some more dusting”, “Lunch is ready” – that highlight the desperate incongruity of the situation. It’s an anxiety that will come close to hysteria when, the sanctum of the apartment breached, the film’s central scene brings the horror of the outside world, in its cruellest sense, into this domestic environment. Surdej’s cinematography helps to raise that sense of tension into something close to terror, while the film’s sound design jolts us back and forth between external and interior spaces, the latter world also defined by Jean-Luc Fafchamps’s minimal score, all piano chords and strings.

The actuality of its subject is bound to make Insyriated powerful, and it leaves a lasting impression, even if, with hindsight, there’s also a certain sense of the formulaic. The only professionals in the cast are Abbass, Abboud and Navis (who is a French actress), the remaining parts played by Syrian refugees in Lebanon, where the film was made. It is nothing less than chilling that the world on screen is so close to their first-hand experience: Insyriated is an urgent film that forces us to confront the desperate human consequences of conflict.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Insyriated

Stephen King’s IT attempted ultimate terror, cutting far deeper than a killer clown. It idealised childhood friendships and their adult honouring even as one of those kids was forced to eat shit by sadistic bullies, and their idyllic small-town of Derry had a stream of child-killing evil running through its sewers.

There are many outstanding things in writer-director Francis Lee’s remarkable first feature, and prime among them is the sense that nature herself has a distinct presence in the story. It brings home how rarely we see life on the land depicted in British cinema with any credibility. God's Own Country is a gloriously naturalistic depiction of the harsh life of farming, of an existence based on close connection to animals and to the earth, set in the Yorkshire countryside in which the director grew up. For a comparable sense of connection to the rural environment, and of the sheer back-breaking work that comes with that link, we have to look elsewhere – to Zola perhaps, or Italian neorealism.

Closer to home there’s much in God's Own Country that resonates with DH Lawrence, his sense of the primal rhythms of life and death, and the way in which the emotions of these working lives are often expressed with a minimum of language. Lawrence has a poem titled “Love on the Farm”, which could work as an alternative title for Lee’s film – except that love is as far from the mind of its main character, twentysomething Johnny Saxby (played by Josh O'Connor), when we first encounter him as anything could be. In an early scene his grandmother catches his character perfectly when she calls him a “mardy arse”, local vernacular for his being moodily withdrawn (it was a nickname that Lawrence was called at school).

The sense of change feels somehow primal

It’s a world in which communication, particularly within the family, is virtually monosyllabic: the first words we hear Johnny speak, some minutes into the film, he addresses to a heifer, and he’s just had his hand inside her to check on her calf (we see a lot of hands exploring animals’ orifices in God's Own Country: Lee made his actors learn such tasks for themselves, no hand doubles here). With his father Martin (Ian Hart) in poor health, Johnny carries the responsibility for the farm on his shoulders, and there’s little else in his life to give it meaning. The fact that he’s gay isn’t an issue in itself – though it’s not spoken of at home – but sex has the same purely physical dimension as the drink he stupefies himself with at the pub every night. When he takes a cow to market, he has a cold fuck with a man who’s obviously an acquaintance, but the idea of continuing any human contact after the act is completed is alien to him.

Johnny’s world is a lonely one: his mother disappeared south at some stage in the past, unable to deal with the isolation and hardship of the farm. Grandmother Deidre (Gemma Jones, playing well beyond her accustomed range) has a sort of scolding affection for him, but she’s more than reserved with her emotions. A childhood friend has come back home for her university holidays – she notices how Johnny has changed, no longer “funny, like you used to be” – and suggests they have a night out in Bradford. When Johnny mentions the idea to his dad, the latter looks at him like he was talking about the moon. All of which makes the arrival of an outsider an unwelcome disruption. Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) has come from Romania to help for a few weeks with the lambing – he was the only applicant for the job – and Johnny’s hostility is immediate as he taunts him as a “gyppo”. They are going up to the higher pastures for the lambing, to sleep in a ruined hut and subsist, it seems, entirely on pot noodles. Then up there, when least expected, fate stumbles in: in this stark isolation the hostility between the two men turns into something else, Johnny’s anger giving way to tussling, and that into physical contact. At first they fight in the mud, rutting like animals, before a deeper contact slowly grows between them. They may still guy one another, but their words – “freak”, “faggot” – are no longer insults, rather signifiers of an new, joshing intimacy.

All of which makes the arrival of an outsider an unwelcome disruption. Gheorghe (Alec Secareanu) has come from Romania to help for a few weeks with the lambing – he was the only applicant for the job – and Johnny’s hostility is immediate as he taunts him as a “gyppo”. They are going up to the higher pastures for the lambing, to sleep in a ruined hut and subsist, it seems, entirely on pot noodles. Then up there, when least expected, fate stumbles in: in this stark isolation the hostility between the two men turns into something else, Johnny’s anger giving way to tussling, and that into physical contact. At first they fight in the mud, rutting like animals, before a deeper contact slowly grows between them. They may still guy one another, but their words – “freak”, “faggot” – are no longer insults, rather signifiers of an new, joshing intimacy.

Lee convinces us of this changing dynamic with absolute filmic subtlety. There’s a sense that the bleak beauty of their surroundings, to which Gheorghe is receptive, has started to infect Johnny too, as does the sheer gentleness of the outsider. We see the Romanian bring the runt of a litter back to life and then, in a truly beautiful scene, coat it in the pelt of a dead lamb so that the mother sheep will allow it to suckle. All of this is conveyed with such tenderness, expressed far more through images than in the very spare words of Lee’s script (his minimal use of music, principally tracks by A Winged Victory for the Sullen, is also all the more powerful for its sparseness). The sense of change feels somehow primal: simply, the two men come down from the hills different people. Johnny has started to feel things that he never knew he could, while for Gheorghe – everything we hear about his back story and homeland is unremittingly pessimistic, “My country is dead” – the possibility of settling, rather than wandering may have become real.

All of this is conveyed with such tenderness, expressed far more through images than in the very spare words of Lee’s script (his minimal use of music, principally tracks by A Winged Victory for the Sullen, is also all the more powerful for its sparseness). The sense of change feels somehow primal: simply, the two men come down from the hills different people. Johnny has started to feel things that he never knew he could, while for Gheorghe – everything we hear about his back story and homeland is unremittingly pessimistic, “My country is dead” – the possibility of settling, rather than wandering may have become real.

For these two who have felt so out of place in their different worlds, the chance to create a home has suddenly appeared, but Lee’s closing reel will test everything. Johnny, although capable of being surprised by joy, remains his own worst enemy: Josh O'Connor’s face has a remarkable, somehow lopsided vulnerability that conveys all that, and more. In these troubled days of Brexit, it’s salutary to find an outsider portrayed with such total respect. However he may have acquired it – most likely, we guess, though the school of hard knocks – Gheorghe has a self-awareness, and a self-sufficiency, that is both beyond his own years, and aeons beyond Johnny's.

Cinematographer Joshua James Richards portrays these landscapes, these faces with a subtle, surprise beauty that matches Lee’s pacing of his emotional narrative. It’s somehow cyclical, how from the barren earth of winter a new harvest will come forth; over the film’s closing credits we see just that, home-movie archive scenes of harvests past. There’s no praising God's Own Country too highly. Francis Lee may have come out of nowhere, but if we see another film as good this year, we will be lucky.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for God's Own Country

Add Una to the ever-lengthening list of mediocre films adapted from fine plays. In London and New York, David Harrower’s Blackbird was an entirely harrowing two-hander: a symbiotic portrait of the damage wrought by desire that also happened to function as a first-class vehicle for actors as disparate as Roger Allam and Jodhi May (in the West End) and Jeff Daniels and Alison Pill (in New York, where Pill was several years later replaced for a commercial run by Michelle Williams).

But in translating for the screen a play he had directed onstage in Germany in 2005, film neophyte Benedict Andrews shows scant evidence of the sense of space and tension and opposites working in conjunction that has marked out his – divisive, in some quarters – local stage revivals of A Streetcar Named Desire and the West End’s current Cat On a Hot Tin Roof.

Vengeance doesn’t adequately describe what is afoot

The combustibility that courses through Blackbird isn’t a million miles removed from Tennessee Williams’s libidinous landscape, at least if Williams had somehow cross-fertilised with Nabokov. But it’s as if in changing Blackbird to go by the title of its distaff character, Una (played by Rooney Mara), the result was a flattening across the board. Less once again turns out to be more, which the play knew and the film does not.

What once seemed ambiguous and subject to revision now seems laboured and overexplicit, and the attempt to open out a purposefully claustrophobic encounter does no one any favours. Harrower adapted his own play, so it seems doubly bewildering that he saw any gain in introducing the character of the barely pubescent Una (played as a 13-year-old by Ruby Stokes) to flesh out a back story that in the play is reported but never shown. The past, as Eugene O'Neill once put it in a different context, functions onstage as the present and the future, too.  The crux of the central face-off remains. The adult Una is flicking one day through a trade magazine – quite why is never explained – when she sees a photo of the man, Ray (Ben Mendelsohn, a terrific actor who should be a bigger star than he is), who led her incipiently teenage self into an abusive, not to mention illegal relationship. Interestingly, the preyed-upon Una was 12 in the play, but perhaps adding a year to the character makes a difference in celluloid funding circles. (Rooney Mara, Ben Mendelsohn, pictured below)

The crux of the central face-off remains. The adult Una is flicking one day through a trade magazine – quite why is never explained – when she sees a photo of the man, Ray (Ben Mendelsohn, a terrific actor who should be a bigger star than he is), who led her incipiently teenage self into an abusive, not to mention illegal relationship. Interestingly, the preyed-upon Una was 12 in the play, but perhaps adding a year to the character makes a difference in celluloid funding circles. (Rooney Mara, Ben Mendelsohn, pictured below)

In any case, Una arrives at the warehouse where Ray works so as to embark upon the wary mating dance-as-reckoning that constitutes the entire play, the scenario tricked out for the film to include a ropey subplot about office politics and an even ropier Other Man, Scott (Riz Ahmed, pictured below with Mara), who is both a nosy parker and a narrative contrivance in one.

When Andrews and Harrower keep to the confines of the material’s essential dynamic, you see vestiges of the nascent power of the piece. Has Ray – who has done time in prison and started life anew with both a wife (Natasha Little) and a new name – put the past behind him? Has Una, and, indeed, can she? The precise reason for Una’s intrepid reacquaintance with Ray is itself properly elusive: vengeance per se doesn’t adequately describe what is afoot.

When Andrews and Harrower keep to the confines of the material’s essential dynamic, you see vestiges of the nascent power of the piece. Has Ray – who has done time in prison and started life anew with both a wife (Natasha Little) and a new name – put the past behind him? Has Una, and, indeed, can she? The precise reason for Una’s intrepid reacquaintance with Ray is itself properly elusive: vengeance per se doesn’t adequately describe what is afoot.

It’s a shame, then, that the ancillary characters merely amplify holes in the plot in which virtually no one seems to be alert to what is going on around them: gathering ambiguity onstage has been replaced by the merely illogical.

Nor do Mara and Mendelsohn feel particularly dangerous as a couple, watchable though they both are. Mara once again is a fundamentally recessive screen presence who seems always to be watching as opposed to participating: a more active performance might provide the missing juice. Mendelsohn admirably projects a world-weary manchild poised between self-knowledge and self-annihilation, but one can’t escape the unfolding awareness that he’s working largely in a vacuum. Blackbird, alas, has flown.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Una

How many more throats must be slit in 19th-century London before the river of blood starts to clot? The Limehouse Golem follows the gory footprints of Sweeney Todd and various riffs on the Ripper legend. Based on Peter Ackroyd’s 1994 novel Dan Leno and the Limehouse Golem, this belated adaptation sensibly ditches the reference to a star of the music hall whose name recognition value isn’t what it was in the late Victorian East End.

Uncovering the identity of the eponymous golem is the hospital pass handed by his superior to Inspector John Kildare (Bill Nighy). The so-called golem, a killer so grim he is popularly assumed to be some sort of Talmudic phantasm, has been carving up randomly selected victims with horrifying thoroughness. At one crime scene a taunting message is scrawled on the wall in blood. Among the suspects are various scholars at the British Library including, randomly, Karl Marx and George Gissing. But Kildare’s more pressing concern is to solve the apparently unconnected death of John Cree (Sam Reid), who has been poisoned in his bed. The maid drops the wife in it and Lizzie Cree (Olivia Cooke) is soon in prison with the mob baying for her to swing. Kildare alone is convinced of her innocence. The accused is a demure little thing who, long before her husband’s death, was already in mourning for the termination of her career as an actress. A series of flashbacks establish that Lizzie has risen to gentility from the poorest circumstances. Her mother turned a blind eye to the molestations of randy old pervs. Orphaned, she drifts towards the local music hall, a place of magical enchantment staffed by dwarves and trapeze artistes, presided over by the celebrated cross-dressing Dan Leno (Douglas Booth, pictured above with Olivia Cooke) and his managerial sidekick known as Uncle (Eddie Marsan in a bald wig).

The accused is a demure little thing who, long before her husband’s death, was already in mourning for the termination of her career as an actress. A series of flashbacks establish that Lizzie has risen to gentility from the poorest circumstances. Her mother turned a blind eye to the molestations of randy old pervs. Orphaned, she drifts towards the local music hall, a place of magical enchantment staffed by dwarves and trapeze artistes, presided over by the celebrated cross-dressing Dan Leno (Douglas Booth, pictured above with Olivia Cooke) and his managerial sidekick known as Uncle (Eddie Marsan in a bald wig).

Lizzie, at this point still a glottal-stopping Cockney sparrow, seizes her chance to become an entertainer by wowing the audience with a popular ditty, and a star is born. She is soon being courted by Cree, a stalker fan/aspiring playwright who eventually persuades her to tie the knot, only to insist she give up the stage. Men are besotted with Lizzie, music hall audiences adore her, and old stage lags think the world of her, while Kildare believes passionately in her innocence. She has to embody virtue, frigidity, pizzazz, ambition, and a little something extra, which is a lot to ask of any actress and it’s no criticism that it feels just beyond the reach of Olivia Cooke. It’s curious to witness Bill Nighy play someone so intensely buttoned up (Kildare’s rumoured homosexuality goes for nothing). The role was originally destined for the late Alan Rickman, and it’s possible to imagine what he might have done with it. Nighy turns in a gimlet-eyed tribute performance which is shorn of all his trademark tics and tricks and doesn’t quite compute. As Leno, Booth channels his inner Russell Brand without conveying the hypnotic appeal that, you assume, was his signature. Daniel Mays plays a PC Plod turn he could do in his sleep. There’s a nice turn from María Valverde (pictured above) as a smouldering other woman.

It’s curious to witness Bill Nighy play someone so intensely buttoned up (Kildare’s rumoured homosexuality goes for nothing). The role was originally destined for the late Alan Rickman, and it’s possible to imagine what he might have done with it. Nighy turns in a gimlet-eyed tribute performance which is shorn of all his trademark tics and tricks and doesn’t quite compute. As Leno, Booth channels his inner Russell Brand without conveying the hypnotic appeal that, you assume, was his signature. Daniel Mays plays a PC Plod turn he could do in his sleep. There’s a nice turn from María Valverde (pictured above) as a smouldering other woman.

London’s underbelly is imagined by an outsider in the form of American director Juan Carlos Medina. There’s a slight school-of-Guy-Ritchie buzz to the chopping edits. The art direction, particularly pleasing in the theatre scenes, leaves little to the imagination at the various Gothic murder scenes. Though the pieces of The Limehouse Golem don’t quite fit together, Jane Goldman’s proto-feminist script saves the best with a splendidly clever twist that rewards your patience.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for The Limehouse Golem

Hearing that a music video director has just made their first feature film generally strikes fear into my heart. But in this instance, Geremy Jasper has done a pretty good job, directing a warm and quirky drama about a young woman from a working-class, chaotic family who dreams of being a famous rapper.

Patti Cake$ is an archetypal indie film, the kind that are acclaimed every year at the Sundance Film Festival by critics sated on Hollywood formula. It won a hefty distribution deal there from Fox mainly because it ticks all the right boxes – it's a character-driven tale told with considerable charm and has a personal backstory – drawn from the writer-director’s own youth growing up in gritty New Jersey and playing in a band.

Danielle Macdonald, with all her bulky charm, is utterly endearing as Patti

Patricia Dombrowski (Danielle Macdonald) aspires to reinvent herself as Killa-P or Patti Cake$ and storm the rap scene with her ingenious rhymes, but the cards are stacked against her. She’s very white, very overweight and very unsupported by her family. There’s an absent dad, a boozing mother with bad taste in boyfriends, and a dying grandmother; Patti is the breadwinner, working shifts in a deadbeat bar. Watching the Australian actress Macdonald who plays Patti swaggering down the street with her headphones on thinking she’s cool, we know that her bubble is due to be popped. Sure enough there are shouts of "Move it, Dumbo!" from a passing car because Patti is someone rarely encountered in the movies – an obese young woman, here owning the main role as opposed to providing comic relief.

Patti Cake$ isn’t simply a white version of Precious or a remake of 8 Miles, though it definitely echoes some of their themes.There’s a standout performance from Macdonald herself and some extraordinary scenes with Scorsese-veteran Cathy Moriarty as Patti’s grandmother who gets involved in her musical endeavours. Jasper's casting ticks a lot of diversity boxes to get the band together: the (gay?) best friend role goes to Siddharth Dhanajay, who works in a pharmacy and sings backing vocals. Then there’s the mysterious heavy metal-goth who lives in a shack in the woods near the cemetery. He barely talks but knows how to mix a track and play guitar. He says he’s the anti-Christ and calls himself Basterd; it goes with his white contact lenses à la Marilyn Manson. Basterd’s played by African-American actor Mamoudou Athie (last seen playing Grandmaster Flash in Baz Luhrman's hiphop saga, The Get Down). Basterd's character evolves and he becomes more than just a memeber of Patti’s band (pictured above).

Then there’s the mysterious heavy metal-goth who lives in a shack in the woods near the cemetery. He barely talks but knows how to mix a track and play guitar. He says he’s the anti-Christ and calls himself Basterd; it goes with his white contact lenses à la Marilyn Manson. Basterd’s played by African-American actor Mamoudou Athie (last seen playing Grandmaster Flash in Baz Luhrman's hiphop saga, The Get Down). Basterd's character evolves and he becomes more than just a memeber of Patti’s band (pictured above).

There’s some slightly clichéd mother-daughter confrontation scenes which are just about salvaged by the ferocity of Bridget Everett’s performance as mom. She's a singer who could have been a contender but is now a lush. Everett is better known as a raunchy cabaret performer and she can really belt out a power ballad at the karaoke bar; her musical style both clashes with and is incorporated into Patti’s band in a slightly hokey finale. This is not a perfect film, some of the plot twists are a little obvious while others defy credibility, but it's hugely enjoyable. There’s some inventive camerawork, excellent editing and a real sense that this is a story that comes from its creator’s heart. And Danielle Macdonald, with all her bulky charm, is utterly endearing as Patti.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Patti Cake$

It’s a road movie, a rites-of-passage drama, a romantic comedy (even a teen sex romp at times), by turns whimsical, brooding and downright dark. Moon Dogs seems pulled in so many directions at once that it’s a wonder the film holds together at all. But hold together it does, and it does far more than that. There’s plenty that’s downright preposterous (more on which later), but it’s a joy of a movie – honest, funny and genuinely touching.

There’s a rare combination of the sacred and the secular in Shubhashish Bhutiani’s debut feature Hotel Salvation (Mukti Bhawan). The young Indian director developed the film through a Venice festival production support programme awarded on the strength of his short film Kush, a prize-winner in 2013, and the combination of different worlds and talents that development process must have involved has worked very well indeed. There’s a rich and moving sense of atmosphere to Bhutiani’s tale of life and death – or, more exactly, the moment when life comes to an end, and a different dimension opens – as well as a father-son relationship that offers an incisive perspective on the values of contemporary India.

Representing an older, almost timeless world is Daya (Lalit Behl). At 77, he’s living his life out peacefully with his family, son Rajiv (Adil Hussain) and his wife and daughter. In contrast, the world of the younger generation is anchored in the stressed routines of the quotidian, particularly for Rajiv, a salaryman who seems always to be up against deadlines, as well as the pressures of an office swamped in paperwork. It makes for a degree of friction at home.

That certainly doesn’t mean the old man can’t be infuriating

But the drama really starts when, out of the blue, Daya announces to his family that he has had a dream that convinced him that his end is near, and that he wants to make a final pilgrimage to die in the holy city of Varanasi. Ahead of that, he ritually donates a calf at the temple, another natural, traditional episode in the wider rhythm of eternity.

Rajiv has permission from his boss to accompany his father to Varanasi, for a notional period at least, although he is still hassled over the phone all the time. They check in at the titular Hotel Salvation, and Bhutiani delights us with some of the other characters in residence. The establishment is run by the eccentric Mishraji, who believes that he knows when each of his residents will die: there’s a limit of 15 days for a stay, though it’s a restriction that in due course will be nicely waived.

The other guests may be waiting for the end, but that doesn’t stop them enjoying more everyday routines, among which is an unlikely evening television show titled Flying Saucer. Daya establishes a particular bond with Vimla (Navnindra Behl), a widow who had accompanied her late husband here years ago and has stayed on ever since. There’s much affectionate humour in their interaction: there’s a moment when Daya appears to be on his deathbed, surrounded by mourners and musicians, with Vimla trying to catch his last words. “What did he say?” a musician asks. “That you sing in tune, please,” she replies.

The other guests may be waiting for the end, but that doesn’t stop them enjoying more everyday routines, among which is an unlikely evening television show titled Flying Saucer. Daya establishes a particular bond with Vimla (Navnindra Behl), a widow who had accompanied her late husband here years ago and has stayed on ever since. There’s much affectionate humour in their interaction: there’s a moment when Daya appears to be on his deathbed, surrounded by mourners and musicians, with Vimla trying to catch his last words. “What did he say?” a musician asks. “That you sing in tune, please,” she replies.

As father and son explore their surroundings, including the sacred river and the ghats that lead down to its banks, they begin to understand one another better; Rajiv comes to reappraise the values of the world by which he has allowed himself to become so absorbed. That doesn’t mean the old man can’t be infuriating – indeed, on occasions he almost seems to relish being just that. But the rhythm of life feels timeless, and Daya in fact appears in better health than ever.

Resist any easy parallels to The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel: Bhutiani directs with great subtlety, drawing out nuances that barely need to be verbalised (if a screen association is necessary, there are resonances with Alexander Payne’s Nebraska). The budget of Hotel Salvation can’t have been large, but the director and his cinematographers Michael McSweeney and David Huwiler relish the different contrasts of light on stone and water, as well as the bright colours of place and attire. Hotel Salvation is a film of great tenderness, one that relishes the details of physical reality, even while acknowledging that leaving all behind is the most natural, even essential thing of all.

Overleaf: watch the trailer for Hotel Salvation