Formed in 1958 by Desmond Briscoe and Daphne Oram, the BBC Radiophonic Workshop pioneered groundbreaking innovation in music making, using anything and everything to create new textures and tones to satisfy eager TV producers looking for otherwordly sounds to lead audiences through their programmes. Although it shut its doors in 1998, the work done there has proved an enormous influence on generations of electronic musicians, from The Human League to Hot Chip, Portishead to Pye Corner Audio, all of whom cite the Workshop as a major inspiration.

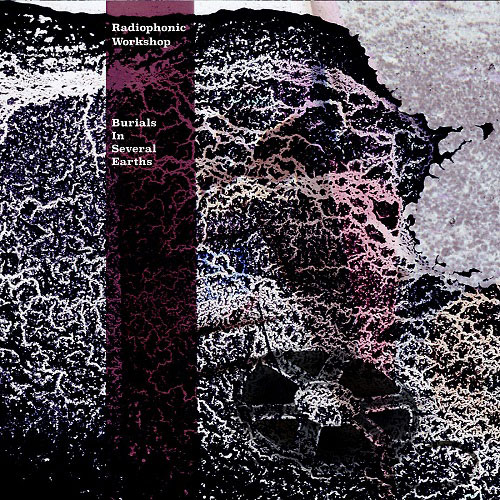

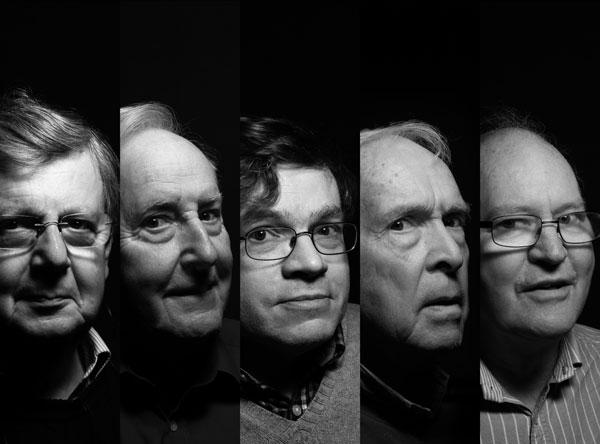

After getting together for a series of gigs under the Radiophonic Workshop moniker, former Workshop composers Dick Mills, Paddy Kingsland, Peter Howell, Roger Limb and archivist Mark Ayres have now recorded an improvised album, Burials In Several Earths and are set to play a special live show at the Science Museum this Friday, 16 June.

Kingsland, who wrote for Doctor Who, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, and became a beat-diggers' hero with tunes such as the sublime "Vespucci" from his 1973 Fourth Dimension album, spoke to theartsdesk about life at the Workshop, the delight of a deadline and the maths of music.

BARNEY HARSENT: How did you first get involved in the Radiophonic Workshop and what was it like to work there?

PADDY KINGSLAND: It was a terrific privilege. When I got there, the old brigade – I’m talking about Delia Derbyshire, Brian Hodgson and John Baker – were still there. I went there on a tour of the BBC as part of a course I was doing. I was working as a studio manager at the time, recording everything from Gene Vincent to Victor Silvester and Jimmy Edwards. I got invited back on attachment and end up there on a permanent basis. When I first arrived, I was helping out Delia and Brian with the things they were working on. This is well after the stage that Delia had produced the Doctor Who theme, but the programme was still going on and Brian was doing all the sound effects for it. John Baker was doing his theme tune work, which was all done with tape and loops, like recording a cork coming out of a bottle and then making it into a tune and cutting all the notes together. The way they worked then was using lots of tape and laboratory oscillators. As I arrived, so did lots of synthesisers – notably a VCS3, a smallish synthesiser made in Britain that I think Delia and Brian had some involvement in. They were great gadgets for making way-out sounds, but they weren’t awfully good at making musical notes because they were slightly unstable. The advantage though, was that you didn’t push a button and get a preset someone else had designed, you had to make your own.

How did the advent of samplers and synths change the working processes and patterns within the workshop? You were among the first musicians to use them weren’t you?

The way we were using them was probably a bit different. The Beatles had already done their stuff with the Moog synthesiser, and there was stuff going on in the industry generally, but we were working to order – with producers who had ideas in mind. The first one was the VSC3 and then they had a gigantic version of that called the Synthi 100 – a huge great box, which hardly fitted… I think we had to take the doors off the studio to get it in! Then the little ARP Odyssey, which I just adored – a lovely little machine from America. We used those ever so much. A little later we had the polyphonic machines and then, of course, machines that had presets ready to go on them, which wasn’t a very good idea really as everyone else had the same sounds as well. Of course, you’d just use those as a starter and then just bend it all around. Once you’d made the sound, you could put it through all sorts of echoes, backwards looping effects and so on. We still did all that tape work alongside it.

When making music to order for programmes, how did deadlines affect the work? Was there a feeling that they hampered the creative process by narrowing the time frame, or did this focus the mind better?

It was fantastic! I usually start the day before the deadline, and mess around a bit too much [laughs]. Occasionally you get producers who say, “I’m coming to you three months early so you can think about it, and I’ll come back with a week to go.” Really what you wanted was someone to come round, tell you what they wanted with a reasonable time to get the job done in – or perhaps not quite enough – otherwise you wouldn’t really do anything. But that’s me – some people love to mull it over gently. Delia used to spend a long time thinking about things, but I think that the deadline in the end was the thing that got her moving and getting things done. I think it’s the same for most people.

Was it easier when it was a commission you were keen on?

It may not be something you particularly want to do, or would have chosen to do, or it may be something that’s absolutely brilliant to do, but if you’re a professional and getting paid for it, you still have to get on and do what’s required. And you get to realise fairly quickly that, if you think it’s going to go one way and your producer thinks it’s going another, in the end it’s going to go their way. You do the best and try to exceed expectations if you can, but you can’t go off and do your own thing, you have to collaborate.

Speaking of which, was the Workshop a particularly collaborative place, or did members tend to work on their own?

It was very much people working on their own thing. Maybe you’d get asked to help out on something, but it really was only helping out. I used to mix things Delia or Brian were doing, because I had a background in that sort of area more recently than they had. They’d work out what they were doing and I’d just keep the levels going. It was great because you learnt a lot from them. I think that Roger Limb and Peter Howell found the same thing.

How did your work on Doctor Who come about and how was it working on the programme?

Do you know, Dudley Simpson – an Australian composer and musical director? He used to be musical director for Margot Fonteyn when she was on tour. He said of Dame Margot that she liked working with him because he was the only person who could make the Perth Symphony Orchestra sound like anything! He was very good at getting quite a bit out of limited resources. Anyway, he worked on Doctor Who for many years – and Blake’s 7 – and he had a small orchestra, which he started out with. He then came to the Radiophonic Workshop, where Dick Mills did a lot of it I think. He got some sounds on the big Synthi 100, which he would then play over the top, so there was a mixture of electronic and orchestral. But it still sounded very orchestral and I think the whole area was going electronic at that time.

In the late 1970s there was a change of direction, [producer] John Nathan-Turner took over Doctor Who and decided he wanted to go another way. I remember doing a demo – I wish I still had it – and Peter [Howell] did one too. We took an episode of Doctor Who and did a cue the way we would have done it. He liked it, so we got the job. Lots of people at the Radiophonic Workshop started doing electronic versions of the music for Doctor Who. I think I did a total of about 28, maybe 29 episodes in all. I did Logopolis, where Tom Baker changes into Peter Davison, which was great fun to do. I didn’t think it was a big deal at the time, because we were just working away and having fun, but it’s lovely that people remember all of that.

Thinking about those pieces of music, some of which you now play live (left: Paddy with Dick Mills), how do you go about restructuring them and stripping out the layers of the programme, the extra context?

We were very much fitting in and fitting around what everyone else was doing, including dialogue. I remember the first gig that we did was at the Roundhouse, and I said, “Well, what we thought we’d do is to get rid of all the unnecessary stuff, like dialogue [laughs]. You know, all that stuff that gets in the way, and just give you the music.” I was being funny, but it was a kind of interesting thing to do, to push through the music as we had originally thought about it. But the audience get the music that was done for the show as it was, really. Often that’s quite difficult to do because in our effort to make it all fit to the pictures and the dialogue, we used to put in all sorts of strange time signatures: 5/4 bars followed by 2/4 bars and then back. That can make it quite difficult to play, but we try to keep it the same. And we were lucky enough to get some of the pictures and dialogue running along with it.

When we’re doing it, I often think that, at a distance, we often did too much. You hear things now and there’s terrifically good TV music and often you hear electronic music used where it’s very spaced out, very sparse and terribly effective. I think we tried to do too much, but then it was that time when I think everyone else was trying to do too much as well.

What happened after the break-up of the Workshop? How did you end up getting together to play live?

I had left the workshop some years before and had my own studio, so was working on that, but then the workshop folded due to certain pressures. It couldn’t keep going for two reasons: equipment had become so much cheaper that people could do it outside the BBC. People like me had been doing it for a while, but then lots of new people came along who could buy equipment which was very cheap and work in their bedrooms. The BBC cottoned onto this and realised they could hire these people; they didn’t necessarily need to force people to go to the Radiophonic Workshop. At the same time the Workshop had costs that were unreal because they had to pay for the canteen and the reception area and all that [part of the much-maligned internal market structure introduced by then DG John Birt]. They couldn’t make it work economically when they were in competition with people who could, frankly, do it in a very tiny space with no overheads.

It was also the end of an era: people could experiment without having the resources of the BBC behind them.

At the end of it all, there was a story going round that all the tapes from the Radiophonic library were in a skip somewhere. I made a couple of phone calls and Brian Hodgson got involved. We decided this shouldn’t happen, so Peter Howell, myself and Brian decided to do something about it. There was some money available to help organise, catalogue and store that stuff somewhere, so it could be used in years to come and kept as an interesting thing.

It was decided that Mark Ayres, a composer and extremely well organised guy, would take this on and we would help him. So that’s how I met Mark and re-met Peter. Someone approached them about a gig at the Roundhouse and they asked me and Roger Limb to join in as old members, so we then made this concert up. It was initially, very frightening as we’d never played together, we were always in little individual rooms on our own, it was never a live thing. So we put together this show, which went well at the time, then nothing much happened for a while. Then we got our manager, Cliff Jones, and we did some more gigs (below at the London Electronic Arts Feastival) and the Burials project.

And now you have a new album on a new label with some very high-profile collaborators. Was it important to do new work to sit alongside the older material – to avoid being a heritage act?

We’ve always been interested in doing new things, we’ve never thought of ourselves as just knocking out the old favourites – although people obviously want to hear those if they come and see us. It was felt that we should be concentrating on something more adventurous and also that collaborations would help us do that. This particular one was Martyn Ware [of Human League and Heaven 17], a great guy and really nice guy to work with and Steve Dub [the Chemical Brothers collaborator].

It was done in a very casual way, a studio was booked and it was me, Mark Ayres and Steve and Martin, and we turned up at this studio in South London, set up all the gear and jammed for a day. We just played and bounced off each other – nothing pre-organised, so it was close really, to doing jazz I suppose.

So it was a completely blind improvisation?

Yes. It wasn’t frightening because we didn’t know much about it before we started and we felt, I suppose, that it was more of a meet up to see how it went initially, but it went quite well and we thought, “Y’know, this sounds quite good.” We recorded tons and tons of material, we didn’t sit around listening to stuff after we’d done it, we thought, ‘”Oh we can do better than that, let’s try this,” and went on to another take of something. Mark got it all and put it together, deciding which bits to use and which parts of each bit to highlight. He was able to mix it all into something that sounds much more… sensible. [Laughs]

There are several nods to the past, with the record label – Room 13 – referencing the BBC studio where they worked, and the references to Francis Bacon’s unfinished New Atlantis poem. Was there a conscious decision to connect the new project to the past? To make sure that there’s a continuum of some sort?

We had that Francis Bacon piece around in the workshop, on the wall, because it was such an interesting thing, referring in a way to the whole audio business as it were [a portion of the poem had been hung by Workshop co-founder Daphne Oram]. That was just part of being around there. Mark was looking around for a peg to hang these improvisations on. It gave him a chance to use lines from the rest of that work and many of the titles on the album (below) came from there.

The room 13 thing is very definitely a tribute, because we’re lucky enough to be taking a bow at the end of it, whereas there are so many people who were around during the Golden Years, like Delia, who really should take most of the credit for this.

The gig on Friday [16th June] at the Science museum is, in part, to celebrate their new mathematics gallery – obviously the workshop was a place of problem solving, but is there a more explicit and practical way in which mathematics guided the work that was done there?

Delia was interested in making things that were very logically worked out. If they were doing a piece, whether it was an abstract piece or a tune like Doctor Who, or one of John Baker’s pieces, they had to do a hell of a lot of measuring of notes using rulers, to say, “Well, if it’s going to be at this tempo, it needs to have, say, three inches, which is a crotchet, at 15 inches per second,” and therefore working out exactly how long you had to have this piece of tape to make a note. And if you want it to be staccato, you have to cut it off, put a bit of spacer in so that you get a short note. If you wanted it to swing, you had to move that slightly, so how do you work out mathematically how you move that note within that framework. John Baker was brilliant at that because he had a jazz feel going along with a lot of his things.

It was trying to do it in an artistic way – with feel – and there’s a lot of mathematics in that. It’s a joining up of people who are highly theoretical and people who are musical and a bit scatty. It’s sometimes difficult, but it can be done. [Laughs]

What can we expect from the gig? Will there be any surprises in store?

All I can say is there will be some improvised stuff to an organised structure, allowing us to improvise rather than play parts. And we’ve got Kieron Pepper who’s a percussionist and drummer [with the Prodigy] who’s absolutely fantastic and who joins us on all of that. He’s very into electronics, so it’s not just drums being played it’s his take on electronic sounds as well.

Of course that will all be together with some of the old favourites, I don’t know which ones yet, but almost certainly the Peter Howell Doctor Who theme!

- The Radiophonic Workshop play at the London Science Museum's IMAX theatre on Friday 16 June

- The album Burials in Earth is out now

- More interviews on theartsdesk

Add comment