theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Matthew Herbert | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Matthew Herbert

theartsdesk Q&A: Musician Matthew Herbert

One of electronic music's most forward thinking brains talks Mahler, Chomsky and Fruit Shoots

Matthew Herbert (b 1972) is a leading experimental musician. His work is sometimes as much sonic exploration as music and mostly inhabits territory where the two realms meet.

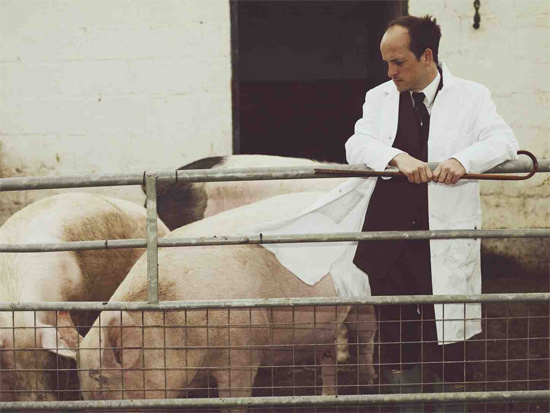

In 2003 his Matthew Herbert Big Band released Goodbye Swingtime and he took an ambitious show on the road, during which a jazz orchestra combined with electronic manipulation. Other experimental shows taken on tour include the very food-centric Plat du Jour extravaganza and, this year, One Pig, which featured the sonic saga of a pig from birth to plate, and included more onstage cookery. He has recently resurrected his Wishmountain persona for a new album, Tesco, wherein each track focuses on one of the supermarket’s best-selling items. He is also working on a new album which will all be based around a single short sample.

When we meet in a central London café he is wearing smart-casual clothes by the Folk label, topped with a box jacket. He refers to this as his “fringes of the establishment look”. He is as bald as but a great deal smilier than his press image and stage persona, his grin dominated by notably gappy front teeth. He speaks with clarity, his manner thoughtful and enthused. He has just come from a BBC Radiophonic meeting so we start by chatting about his new role there…

When we meet in a central London café he is wearing smart-casual clothes by the Folk label, topped with a box jacket. He refers to this as his “fringes of the establishment look”. He is as bald as but a great deal smilier than his press image and stage persona, his grin dominated by notably gappy front teeth. He speaks with clarity, his manner thoughtful and enthused. He has just come from a BBC Radiophonic meeting so we start by chatting about his new role there…

THOMAS H GREEN: What does it involve?

MATTHEW HERBERT: It’s up to me to define it. I absolutely have to be in line with what it previously was. It’s attached to www.thespace.org. No one knows about this but it’s a big Arts Council/BBC project, free online, 24 hours a day, all the Shakespeare plays at the Globe, all the Royal Opera House, John Peel’s record collection, spoken word, a big platform for all the contemporary arts in England.

So the BBC Radiophonic Workshop will no longer be taking their most famous role – soundtracking Doctor Who?

I’d like to do a special episode. Those associations are from a very particular time when [the BBC Radiophonic Workshop] were thinking about the future, using machines to see what the future might sound like. Well, we’re sort of in the future now, you can make a piece of music by stroking a piece of glass in your pocket and send it to Brazil in 30 seconds. So now what? There’s such an excess of music, an outpouring of ideas and thoughts from everybody. Actually its creating a huge wall of noise and it’s getting harder and harder to pick your way through it.

There’s a lack of gatekeepers?

I have read the statistics that 75 percent of iTunes has never been downloaded. That’s an extraordinary amount of music. I feel we should maybe stop making music until we’ve listened to that, then start again. It seems only fair to the people who’ve made it all.

Advances in communication technology have made it increasingly difficult to make money both in my world, as a writer, and yours, as a musician.

Record sales are over across the board so it becomes much more about a live experience. A lot can come through advertising. It’s extremely hard to avoid your music being used in advertising.

Your new album is called Tesco. Do you think that might accidentally advertise Tescos?

Your new album is called Tesco. Do you think that might accidentally advertise Tescos?

I wanted to make an old-fashioned dance record in a few days. My big records took a huge amount of my time. I do a lot of interviews and there’s obviously controversy about aspects of it. Before that I’d done a big band with 400 people, thousands of recordings - I just wanted a week off. Basically, I’m free to do whatever I want so I wanted to remind myself I can do that. I killed off Wishmountain a few years ago so I thought about reforming like Heaven 17 or something. I reformed with myself. I’d wanted to do something about supermarkets for a while but I didn’t want to do another grand gesture. I loved the idea of reclaiming the word “tesco” and putting it into a different context. Instead of it being a negative thing, which it is to me, I don’t want to be critical of the people that use it but as an institution, it’s the biggest supermarket, and I chose the ten most popular brands as my subject.

I was surprised that one of them was Fruit Shoots?

It is odd. Toilet roll you’d expect, bread you’d expect, coffee, Dairy Milk, but Lucozade is another one I was surprised at.

A generation of ravers growing old...

[Laughs] Exactly! Fruit Shoots is as surprising. What I hate is that it has the word "fruit" in it and it hasn’t really got any fruit in it - acid flavour, horrible sweeteners. I like that the record is a simple democratic little statement. I didn’t want to make a big gesture or pontificate, I just wanted to do it and let the objects, the words and music do some of the work. Also it’s dance music so it’s designed to be a moment rather than a long multi-levelled narrative.

What is it about food that makes you constantly return to it in your work?

First, because I think it’s the front line of how we express ourselves, something we have to do two or three times a day. These are choices we make, decisions that have a vast impact somewhere in the world. Secondly, the biggest consumer of oil is food so when we talk about wars, Iraq, climate change, population, so much of it comes back to oil. Food is the number one consumer of oil. The tea bag you had at breakfast, the coffee I’m drinking, all those things become the tip of an iceberg. I like the idea that something as disposable as a cup of coffee contains such a history, so many stories. The Vietnam War and the price of coffee, for example - the Vietnam coffee fields were imposed by the IMF after the Vietnam War. For me food summarizes so many of the problems we have today. We’ve designed a system to do the wrong thing at the wrong time.

You’re suggesting that food has an ongoing socio-political narrative that you’ve turned into art?

You’re suggesting that food has an ongoing socio-political narrative that you’ve turned into art?

It’s always there, whether you listen or not. As a storyteller, they’re some of the most profound, depressing and amazing stories about what we put in our bodies and why we put it in our bodies. You look at the rise of the transnational organization - McDonalds, Starbucks, Coca Cola – they’re all food companies. It’s also something we could easily change. You could not shop in supermarkets, one of healthiest things you can do for yourself, and that gives you wider control.

Why’s it so important to you to gather field recordings from specific locations? For instance, with your reworking of Mahler’s tenth symphony for Deutsche Grammophon you made recordings on the Italian Tyrol in the hut where he composed?

With regard to sound, the first thing everyone does is shuts the world out in a recording studio, put cloth on the walls, sponge on the ceiling. I made a deal with myself a few years ago to only record outside the studio, to go out into the world. It changed everything and had a huge impact. There’s a fundamental revolution in music in that it’s now a documentary when for for four million years it was impressionism. It used to be that if I wanted to write a piece of music about this cup of tea I’d have to imitate it and describe how I felt about it through musical metaphor. Now I can take the sound of the tea spoon and pouring and make a piece of music out of it. I feel like a documentary maker, it’s about bearing witness. These are things I’ve seen and how they’ve made me feel, physically. Mahler is a good example. If you go to his hut the first thing you hear is pigs. The guy who’s responsible for maintaining it can’t afford to so he sticks farm animals round it and you have to pay to see the pigs to visit Mahler’s hut. Secondly there’s the road, a big one with traffic noise that wasn’t there when Mahler was. He went there because he wanted silence. That immediately tells you something. It unlocks whole levels and layers of stories you never would by sitting at home.

Watch mini-documentary about Matthew Herbert's work on Mahler's tenth symphony

About a decade ago you wrote A Personal Contract for the Composition of Music, a manifesto that struck me as the sonic equivalent of Lars von Trier’s Dogma theories.

Yes, technology has made it incredibly easy to make music but it’s also guiding us. You load it up and it’s immediately in 4/4, 120 BPM, drum machine, synth, it shapes the music, shapes how we express ourselves. The idea of the manifesto is to forget that: (a) what’s the idea and (b) take responsibility for every step you can. That’s no big deal in acoustic music. If you’re playing piano you don’t think, “I’ll add a bit of Hank Marvin to a bit of Bill Evans to a Take That middle eight with a Tom Waits bridge,” but in electronic music it’s almost like a consumer version where you assemble things from component parts. The manifesto is there to try and encourage me not to do that.

As a boy were you obsessed with sound or were you more of a late developer?

A late developer. It was the technology. The great developments in music have come from technology – valves on the trumpet, the piano, computer, sampler. I was lucky to be in right place at the right time - when I was 16 samplers became affordable. That was revolutionary to me, changed the way I felt about the world, about politics about music, about myself.

What do your parents do?

My mum was a school teacher, my dad was an engineer at Broadcasting House, on the radio, so we did have technology about, not afraid of it. I grew up without a TV as well, so listening was an important part of it but technology made the difference.

How much of a role did the electronic dance music explosion of the Nineties play? How much was rave and how much was BBC Radiophonic-style sound exploration?

At beginning I was at university in Exeter and there was an amazing free party movement in the West Country. There was also a shop called Mighty Force which released the first Aphex Twin record and released my first record so we were part of a very exciting little West Country thing. We’d make something up in the day then at night stand in a field with 400 strangers listening to this new form of dance music. It gave this weird friction that’s still present in my music. I still DJ in nightclubs all round the world, partly becaue I’m expected to do it and partly because records don’t sell any more.

When did you buy your first electronic kit?

When did you buy your first electronic kit?

I had a synthesizer at 13 and a four track tape machine but it was the sampler that really made the difference, a sequencer as well, being able to free up your hands to do other things. I played piano and violin from the age of four, and played in a big band when I was 13. I did an orchestra, you had to get everybody together in the church hall, music stands and so on,

Where was that?

Kent, Tonbridge, it was always such a logistical issue getting everyone together. Electronic music was a great liberator. You could play the bassline yourself and then play the keys and then a drum part.

Why did you study drama at university given all this musical background?

Part of me had a fundamental disconnect with how music was taught then. In a classical sense you were a bad musician if you played a wrong note. I didn’t recognise that. It didn’t feel like an artistic expression, it felt like a discipline and a craft, which I have utmost respect for, but what was most exciting to me was thinking about new ways of organizing things. There were also a lot of Bach chorales at university at that time and no technology department as there is now. I got a C at music A Level. I wasn’t that interested in notated music, I was much more interested in taking control of that process.

In terms of drama, performances of yours, such as the recent One Pig shows with their white butchers’ coats, onstage cookery and musical “sty”, are a form of theatre, in any case. At the end of One Pig and on your One One album you do some singing – are we going to hear more of that?

I generally hope you’re not going to hear more of it. I like singing to give people a little icon on the map where I expose myself, in a way – “This is how my songs are imagined” - but I’m not a singer and not comfortable doing it. I work with so many incredible people, from musicians to playwrights, Heston Blumenthal to Punch Drunk Theatre to Sigur Ros, so the idea of me croaking my way through seems absurd when I call the best singer in Britain.

Yes, but on the other hand, variety in vocal styles is healthy, like the freedom punk gave singers. At the moment there’s a sense that if you try and sing like Mariah Carey it somehow expresses real emotion yet Ian Dury’s voice, hardly a classic instrument, conveys far more emotion. So did you feel excruciated on stage singing at the end of One Pig.

I quite liked that because it’s so extreme after all that came before. It makes you realise how far you’ve come sonically although my debut was at the Royal Opera House and I thought, “I’m probably worst bloody singer to have graced this stage.”

Watch a mini-documentary about One Pig

At One Pig in Brighton there was an animal rights protest outside the theatre. You’ve had this reaction before to your productions that utilise meat. What’s your reaction to them?

It seems to me they’ve missed the point entirely, but it’s not the first time I’ve had animal rights issues. I found it very annoying then very exciting but the vast majority of complaints came before the record was made and before I’d even written any music so I was very happy that my idea for a piece of music could stimulate that kind of outrage. I’m really interested in how Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring caused people to riot [in Paris in 1913]. The fact they rioted at a piece of instrumental music makes me wonder what piece of instrumental music would make people riot now. Music can have real political and social power but now it’s the soundtrack to perfume ads and in hotel elevators, the background to sports commentaries, it’s always serving a function and it’s pretty blatant what that function is.

What are you reading at the moment?

Mrs Bridge [by Evan S Connell], an American classic about a suburban housewife going through very subtle existential crises. Nothing happens in the book, she just goes and buys cake and things. I’ve just ordered David Byrne’s book about how music works, I’m interested in what he has to say. And I still can’t stop myself devouring everything Chomsky writes. He has a very bad reputation from people who never read him but actually I find him incredibly engaging and thoughtful and precise. “Chomsky” is now a dirty word but he’s true to the fact that when you’re living in such a corrupt system it’s important how you respond to the details. I’m as much of a hypocrite as anyone else. I might drive to a gig rather than fly but I’m still putting petrol in the engine, still shipping little circular bits of plastic round the world. His political writing helps in constructing music, taking responsibility for every component and not just vomiting out ideas and hoping someone will pick the carrots out of it. There’s a really unhealthy common assumption within our society that because we have a right to express ourselves we also have a right to be heard. I don’t think those two things are necessarily joined up.

Have you ever found psychedelics or narcotics creatively useful in your working life?

[Laughs] You know what, in about 5000 interviews no-one’s ever asked me that. I think at the right time in the right place the right drug can be a really interesting and useful part of thinking about things and seeing them in a different way. Having said that, any time I’ve ever been a bit drunk I can’t operate the equipment, you lose perspective. I’m a big believer in doing things well and taking drugs can remove you from the act of creation, of taking part in the world, so occasionally I may have done drugs in the past but never in the studio in that way.

Of all the places you’ve done field recordings, which was the least pleasant?

Of all the places you’ve done field recordings, which was the least pleasant?

The first answer you’d probably think would be the sewers under Fleet Street [for 2005’s Plat du Jour] but actually that was alright, sewers are 85 percent water. The supermarket broiler chicken farm was unbearably awful because chickens come into the shed, there’s no natural light, they live there, shit, at least 10% die in there then they’re put in a truck, so they live amongst their own shit, ammonia, chicken smell, antibiotics, a very, very pungent acrid smell, deeply unpleasant and not at all healthy.

Tell us about Roisin Murphy. Right back to her days in Moloko you have often worked with her and your careers have crossed paths on numerous occasions. Why is that?

She should be a really engaging and interesting pop star but the way record companies are set up these days they don’t support or nuture that so, for example, [Murphy’s 2005 album produced by Herbert] Ruby Blue they killed, the record company blatantly killed it, pulled all funding from it. It went on to sell a lot of copies and had great success in America on TV shows but the label didn’t get it. I had a very mainstream musical upbringing, my main childhood listening was Radio 1 and my dad’s record collection in a small village. Also I went to church every week so even though I'm now involved in a much more experimental approach there’s still that pop sensibility locked in there somewhere, the idea you haven’t really succeeded if you haven’t been on Top of the Pops, had a number one. I’ve got to the point in my life where I’ve realised a number one hit is a bit of a curse in many ways, a focal point around which everything else is measured. That could be extremely destabilizing. In Roisin – who’s had a lot more success than I have – I see that tension between art and populism.

Watch the video for "Sow Into You" by Roisin Murphy, produced by Matthew Herbert

Imagine being The Rembrandts, being globally known soley on the basis of the theme from Friends.

Everyone coming to your concert waiting to hear that one bloody piece of music.

Tell us about the Museum of Sound [www.museumofsound.com] which will shortly be resurrected.

To me this is most exciting to work on. It’s essentially an interesting step forward in thinking about sound. There’s nowhere to listen to 1982 on the internet, nowhere to listen to Great Portland Street or this café, so first it’s simply an archive for documenting all that stuff. Secondly, you can now just listen to sounds recorded on a Monday or sounds recorded by women or sounds recorded in Belgium or after midnight. You can listen to the world in denominations of sound, have things side by side and what they might mean. I can’t wait to get it up and out there. It’s been a year in development. I launched it in 2007 and we got spammed out of existence very quickly. There really wasn’t the interest then, there’s much more now.

Tell us some of your future plans.

Tell us some of your future plans.

I’m going to make films, make a feature film, a musical about sound. I’ll make a short film first. I’m devising a play at the National Theatre, starting to move into the visual medium. I also want to do something optimistic. I had this really weird thought that the next record should be a happy record. What am I happy about apart from my family? I’ve been starting to feel weird about happiness. There really isn’t that much great proper happy music, there’s always degrees of melancholia in music as a form.

What about “Dancing Queen” by ABBA, that’s pretty happy?

But is it? Really? I must check the lyrics. Even the Beach Boys had the context of the fact Brian Wilson was so incredibly unhappy, tortured writing this jolly music.

Have you had any other jobs but music?

I worked in bus insurance for a summer. I went for an interview as a weather man but didn’t get it. I worked assembling garden furniture. I worked in a bike shop. I did carpet cleaning sales for a while but that was absolute disaster, I didn’t sell anything at all. They gave me this preparatory lesson on how to force your way into people’s homes, point out how flthy their carpet was, then hijack their phone to call central office to get a decent price for them. It was not in my DNA.

Popular music, the charts and so on, is in a very bland stasis currently. In the past, prior to all great sweeping changes – such as punk, acid house, rock’n’roll - there was always a very boring period where people almost had to look backwards to move forwards. Are we in one of those times or do you think technology has moved music culture beyond such cycles?

We’re close to thinking about moving beyond it but, for me, we’re really not. To me the revolution is making music out of noises. I can now make music out of the Syrian revolution or David Cameron or a piece of toast. For me that’s way more interesting a concept than anything I could possibly do on a piano. Every time I sit at a piano to create a piece of music I feel incredibly impotent, up against four billion other people who’ve written on the piano, from Thelonius Monk to Brahms, both of whom I’m never going to equal in terms of their abilities or the way they could put things together. But neither Brahms nor Thelonius Monk had a toaster or the Tory party as part of their musical armoury. For me that’s the spark, the ignition for the next revolution in music.

And you’ve been firmly sticking with it.

Yeah [laughs], it fucking better be otherwise I’ve wasted 30 years of my life!

Watch a belting clip of the Matthew Herbert Big Band with Dani Siciliano

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Ed Sheeran - Play

A mound of ear displeasure to add to the global superstar's already gigantic stockpile

Album: Ed Sheeran - Play

A mound of ear displeasure to add to the global superstar's already gigantic stockpile

Album: Motion City Soundtrack - The Same Old Wasted Wonderful World

A solid return for the emo veterans

Album: Motion City Soundtrack - The Same Old Wasted Wonderful World

A solid return for the emo veterans

Album: Baxter Dury - Allbarone

The don diversifies into disco

Album: Baxter Dury - Allbarone

The don diversifies into disco

Album: Yasmine Hamdan - I Remember I Forget بنسى وبتذكر

Paris-based Lebanese electronica stylist reacts to current-day world affairs

Album: Yasmine Hamdan - I Remember I Forget بنسى وبتذكر

Paris-based Lebanese electronica stylist reacts to current-day world affairs

theartsdesk on Vinyl 92: Marianne Faithful, Crayola Lectern, UK Subs, Black Lips, Stax, Dennis Bovell and more

The biggest, best record reviews in the known universe

theartsdesk on Vinyl 92: Marianne Faithful, Crayola Lectern, UK Subs, Black Lips, Stax, Dennis Bovell and more

The biggest, best record reviews in the known universe

Add comment