Sci-Fi Week: Space Rock | reviews, news & interviews

Sci-Fi Week: Space Rock

Sci-Fi Week: Space Rock

Rock and pop’s fascination with realms beyond the Earth’s atmosphere

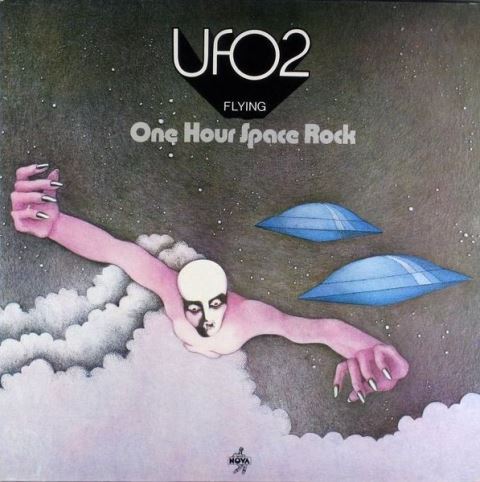

In 1971, the British rock group UFO released their second album. Titled One Hour Space Rock, its cover bore the subtitle Flying and, yes, images of UFOs in the form of flying saucers and a bald, naked and pink humanoid with claw-like fingernails. Musically, although the album had its freaky sections and sported the lengthy tracks "Star Storm" and "Flying", what was on offer was mostly day-to-day blues-rock.

Nonetheless, this was an overt acknowledgment that rock music was on a more-than-nodding acquaintance with the concerns of science fiction. One Hour Space Rock wasn’t a bestseller and UFO would only go on to great success after German guitarist Michael Schenker joined them.

Rather than UFO, Hawkwind were the band which would musically define space rock, especially with the 1971 and 1973 albums In Search of Space and Space Ritual. Initially, they hadn’t explicitly labelled themselves space rock, but Hawkwind were the real deal – they even collaborated extensively with science fiction author Michael Moorcock. Their music drew on drones, was repetitive and evoked movement and the vast emptiness of space. It was no coincidence that the musical journey to outer space mirrored the drug-assisted journey to inner space. If suitably dosed, they could be one and the same. (pictured right, UFO's One Hour Space Rock)

Rather than UFO, Hawkwind were the band which would musically define space rock, especially with the 1971 and 1973 albums In Search of Space and Space Ritual. Initially, they hadn’t explicitly labelled themselves space rock, but Hawkwind were the real deal – they even collaborated extensively with science fiction author Michael Moorcock. Their music drew on drones, was repetitive and evoked movement and the vast emptiness of space. It was no coincidence that the musical journey to outer space mirrored the drug-assisted journey to inner space. If suitably dosed, they could be one and the same. (pictured right, UFO's One Hour Space Rock)

With their minimalism and penchant for repetition, Hawkwind drew from early Krautrock but they had other sonic forebears. In 1967, The Beatles had recorded the soaring instrumental “Flying” for the Magical Mystery Tour soundtrack. The Rolling Stones had also issued "2000 Light Years from Home" in 1967 on the Their Satanic Majesties Request album. It was also sonically flowing and as spacey as “Flying”, and found Mick Jagger declaring “we're setting off with soft explosion, bound for a star with fiery oceans”. Great though it was, it was not The Rolling Stones' new direction.

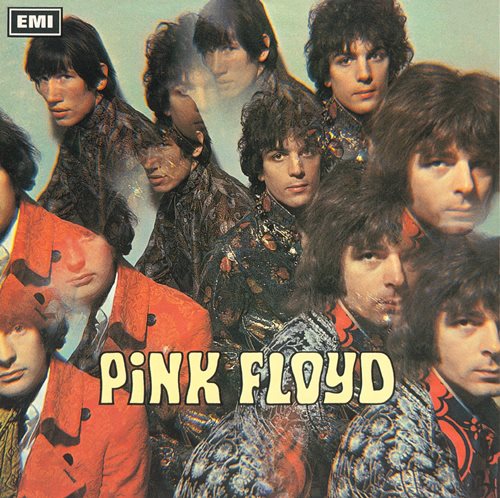

For The Beatles and the Stones, tipping their hats towards the spacey were side issues. It was core to Pink Floyd though. Their first album, 1967's The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, included the epic instrumental “Interstellar Overdrive” and the ever-amazing “Astronomy Domine”. After their inner-outer space voyager and lynchpin Syd Barrett left, Piper's follow-up A Saucerful of Secrets featured the extraordinary Roger Waters-penned “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun”. From this benchmark, Pink Floyd went on to define a space rock less jagged than Hawkwind’s but one which nonetheless also delineates the genre. No Pink Floyd, no Alpha Centauri by Germany's Tangerine Dream. (pictured left, Hawkwind's Space Ritual)

For The Beatles and the Stones, tipping their hats towards the spacey were side issues. It was core to Pink Floyd though. Their first album, 1967's The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, included the epic instrumental “Interstellar Overdrive” and the ever-amazing “Astronomy Domine”. After their inner-outer space voyager and lynchpin Syd Barrett left, Piper's follow-up A Saucerful of Secrets featured the extraordinary Roger Waters-penned “Set the Controls for the Heart of the Sun”. From this benchmark, Pink Floyd went on to define a space rock less jagged than Hawkwind’s but one which nonetheless also delineates the genre. No Pink Floyd, no Alpha Centauri by Germany's Tangerine Dream. (pictured left, Hawkwind's Space Ritual)

It wasn’t only European bands and the David Bowie of “Space Oddity” that were looking heavenwards. In 1967 (again), folk-rock pioneers The Byrds recorded the whimsical “CTA-102” – which took its title from a quasar and featured "alien" voices – for their Younger Than Yesterday album (below: listen to it overleaf). But it was The Grateful Dead who perfected an American space rock, notably with the ever-morphing live staple “Dark Star”, initially issued as a single in 1968 (listen to it overleaf). In 1974, the song's title was borrowed by the John Carpenter eponymous science fiction film.

Before the psychedelic era, aliens and outer space were usually fodder for American novelty records. Prime examples include Billy Lee Riley’s scorching “Flying Saucer Rock ’n’ Roll” (listen to it overleaf) from 1957 and The Ran-Dells utterly brilliant 1963 single “Martian Hop” (listen to it overleaf). (pictured right, Pink Floyd's The Piper at the Gates of Dawn)

Before the psychedelic era, aliens and outer space were usually fodder for American novelty records. Prime examples include Billy Lee Riley’s scorching “Flying Saucer Rock ’n’ Roll” (listen to it overleaf) from 1957 and The Ran-Dells utterly brilliant 1963 single “Martian Hop” (listen to it overleaf). (pictured right, Pink Floyd's The Piper at the Gates of Dawn)

More serious pre-psychedelic musical appraisals of realms beyond Earth came from maverick British producer Joe Meek. In 1959 he created I Hear a New World: An Outer Space Music Fantasy, which was intended to be an album. One EP was barely issued in 1960 in an edition of 99 and the album itself only reached the test-pressing stage. It was released in full for the first time in 1991. In his liner notes for the EP, Meek said, "This is a strange record, I meant it to be." It was. He imagined a moon populated by such creatures as the “happy, jolly” globbots and “rather sad” sarooes, and soundtracked their world with primitive electronica. Meek’s 1962 instrumental hit “Telstar”, which he invented for the Tornados, was easier to digest, a hit world-wide and remains a classic slice of proto-space rock.

Almost as obscure was a 1962 single credited to Ray Cathode. Produced by soon-to-be fifth Beatle George Martin, it was actually by staff from the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. Its B-side was the Dave Brubeck-inflected “Waltz in Orbit", a bizarre, almost concrête soundscape which actually did sound otherworldly (listen to it overleaf).

Looking forward from the psychedelic era and by-passing prog and over-the-top albumslike Absolute Elsewhere's is-God-an-astronaut-inspired In Search of Ancient Gods, punk had little time for space and aliens. In the Eighties, Spacemen 3 would map a new space rock which resonated through shoegazing and still does with bands like Hookworms.

But there were odd flashes of a science-fiction influence in the post-punk fallout. Joy Division were informed by bookworm singer Ian Curtis's fascination with author JG Ballard’s dystopian fiction. Fittingly though, it was the reliably contrarian Stranglers who turned space rock on its head with the paranoid and for-real frightening “Meninblack” from their disturbing 1979 album The Raven. Listen to it overleaf, but do not do so in the dark.

Listen to The Grateful Dead’s “Dark Star” (original, single version)

Listen to The Byrds’ “CTA-102”

Listen to Billy Lee Riley’s “Flying Saucer Rock ‘n’ Roll”

Listen to The Ran-Dells’ “Martian Hop”

Listen to Ray Cathode’s “Waltz in Orbit"

Listen to The Stranglers’ “Meninblack”

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Kali Malone and Drew McDowell generate 'Magnetism' with intergenerational ambience

Young composer and esoteric veteran achieve alchemical reaction in endless reverberations

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Benson Boone, O2 London review - sequins, spectacle and cheeky charm

Two hours of backwards-somersaults and British accents in a confetti-drenched spectacle

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

Midlake's 'A Bridge to Far' is a tour-de-force folk-leaning psychedelic album

The Denton, Texas sextet fashions a career milestone

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

'Vicious Delicious' is a tasty, burlesque-rockin' debut from pop hellion Luvcat

Contagious yarns of lust and nightlife adventure from new pop minx

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

Music Reissues Weekly: Hawkwind - Hall of the Mountain Grill

Exhaustive box set dedicated to the album which moved forward from the ‘Space Ritual’ era

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

'Everybody Scream': Florence + The Machine's brooding sixth album

Hauntingly beautiful, this is a sombre slow burn, shifting steadily through gradients

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Cat Burns finds 'How to Be Human' but maybe not her own sound

A charming and distinctive voice stifled by generic production

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

Todd Rundgren, London Palladium review - bold, soul-inclined makeover charms and enthrals

The wizard confirms why he is a true star

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

It’s back to the beginning for the latest Dylan Bootleg

Eight CDs encompass Dylan’s earliest recordings up to his first major-league concert

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Ireland's Hilary Woods casts a hypnotic spell with 'Night CRIÚ'

The former bassist of the grunge-leaning trio JJ72 embraces the spectral

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Lily Allen's 'West End Girl' offers a bloody, broken view into the wreckage of her marriage

Singer's return after seven years away from music is autofiction in the brutally raw

Add comment