A couple of weeks ago on BBC’s Question Time one of the pundits airily commented that until recently no-one in the audience would have heard of Bamako, the capital of Mali. That wouldn’t be the case were there any world music fans there – for them, the country (perhaps only with Cuba as a rival) has the strongest and most renowned music heritage anywhere.

There are more general reasons for the supremacy of Malian music, including its accessible, bluesy sounds and the fact that Francophone African music has always had a boost through Paris, the most global-music-friendly city in Europe. More local and specific reasons are that that influential individuals in the UK like presenter/producer Lucy Duran and Nick Gold, of the most successful world music record company World Circuit, have adored and promoted Malian music here for decades.

What was unusual in recent weeks was how much of the political coverage of Mali has been by journalists known for their music writing, like artsdesk contributor Andy Morgan, Robin Denselow or Ian Birrell (David Cameron’s ex-speechwriter and co-founder of Africa Express), who all supported the French intervention. The underlying message “Without music, there is no Mali” (as theartsdesk’s review of a recent concert was subtitled) fuelled outrage at the Islamic fundamentalists who had overrun the north of the country.The Islamic fundamentalists were guilty of all kinds of barbarism, but banning music was high on the list. Other acts of cultural vandalism included destroying the Sufi shrines and ancient Islamic texts in Timbuktu, as Sophie Sarin describes elsewhere on theartsdesk.

A central figure in the Mali music scene is Bassekou Kouyaté, whose new album Jama Ko is a call for peace and tolerance. He is a master of the ngoni and has appeared on many of the key Malian albums of recent years, including the Afro-Cubism album, Savane, with the late blues maestro Ali Farka Touré as well as his own award-winning solo albums with his band Ngoni Ba. In live performance he packs a punch, as Howard Male noted on theartsdesk: “I’ve yet to witness an audience that hasn’t been pulled into their vortex of duelling ngonis, thumped and slapped calabash and sweet and soaring vocals.” He appeared on stage with Sir Paul McCartney at last year’s Africa Express, and was also in the recent Mali-Ko video for peace, organised by rising star Fatoumata Diawara (see below).

The video, featuring musicians from assorted ethnic backgrounds, was as much about promoting peace within the factions of Mali for internal consumption as much as raising awareness outside. The fact is that many Malians blame the nomadic Touaregs for the current woes in the country. The Touaregs' rebellion and attempt to set up an independent homeland in the north, which they dubbed Azawad, was then usurped by the Islamic radicals, and this triggered a coup which ousted the President, a friend and sponsor of Bassekou’s. It would be fair to say that many ordinary Malians currently loathe the Touaregs for their act of insurrection which split the country.

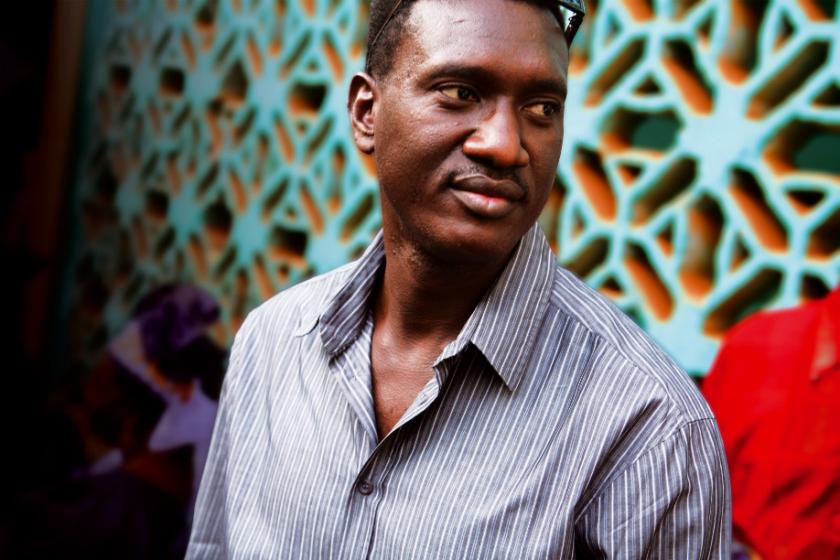

Kouyaté talks about the situation in Mali, overleaf

So when I met Bassejou at the end of last month at a concert at the Barbican called Sahara Soul, which featured both his band and a Touareg band, Tamikrest, I was curious to hear his view. Relaxed in the backstage area and softly spoken, he said that as long as the Touaregs gave up their plan for an independent country (and, after all, they are one of many ethic groups in the north) he had no problem, and was glad to share a bill with a Touareg band. "We are all part of one country and all have our point of view," as he put it. Whether the Touaregs will give up their long cherished dream of a homeland is one of the unanswered questions of the unfolding situation in Mali.

He was thrilled by the intervention of the French. “Vive la France!” he said, adding that he had a tricolour flag flying at home in Mali. “Thank you France, thank you England, for saving our children,” he said, breaking into English. He says while things are fairly calm in Bamako, everyone has cancelled their weddings and there is a general sense of nervousness. Things are bad for musicians even in areas not embroiled with the Islamic rebels.

The title song of his current album is called "Jama Ko" (“Big Gathering”). “The bandits want to destroy us, they want to divide us. Mohammed himself had musicians at his house and we have been singing his praises for hundreds of years. Mali is a tolerant place. Christians, Muslims, animists all living together. And having a party.”

In fact, politics intruded on the album from the start, as “the day we started recording the coup d’état happened. We could have given up, but we refused to.” The album, an eclectic wonder sumptuously produced by Howard Bilerman of Arcade Fire, is a family affair with his wife, Amy Sacko, singing as well as including two of his sons in his band. Standout tracks include "Sinaly", a bowdlerised version of a 19th century tale of a king resistant to Islam (the original story is considerably more rude), a paean to great Bambara warrior “Segu Jajiri”, and a grooved-up celebration of cotton farmers called “Mali Koori,” all featuring the part-harp, part-cricket bat ngoni, played with exquisite brilliance.

Toumani Diabaté could trace his family back to the 13th century. Bassekou can do better than that: 'I can trace my family to before Jesus Christ'

When I ask him why he thinks Malian music has such a resonance in the West, he says it’s probably because Mali was the birthplace of the blues music which underlies so much American pop (a guest on the album is his old friend, the veteran American bluesman Taj Mahal).

The other important thing about music from Mali which he thinks gives it its depth is the tradition. When I spoke to the kora maestro Toumani Diabaté, he said he could trace his music and family back to the 13th century. Bassekou can do better than that: "I can trace my family to before Jesus Christ”.

Central to the tradition are the griots, or praise singers, who memorise families going back many generations. His family has their own griot, while he acts as griot to the deposed President Amadou Toumani Touré (ATT for short), which means acting like a singing PR. “I speak to ATT quite often, he’s now in Senegal.”

He hopes for ATT’s return, and although the Islamic radical threat will hardly disappear completely, he thinks that within a year, things will be normal enough for the fabled Festival in the Desert to reappear in Mali, which he will be supporting and be there to celebrate. The traditions will live on. “The next generation will take this music and make it new – it won’t stop with me. That I am sure about, in’shallah.”

Follow Peter Culshaw on Twitter

Add comment