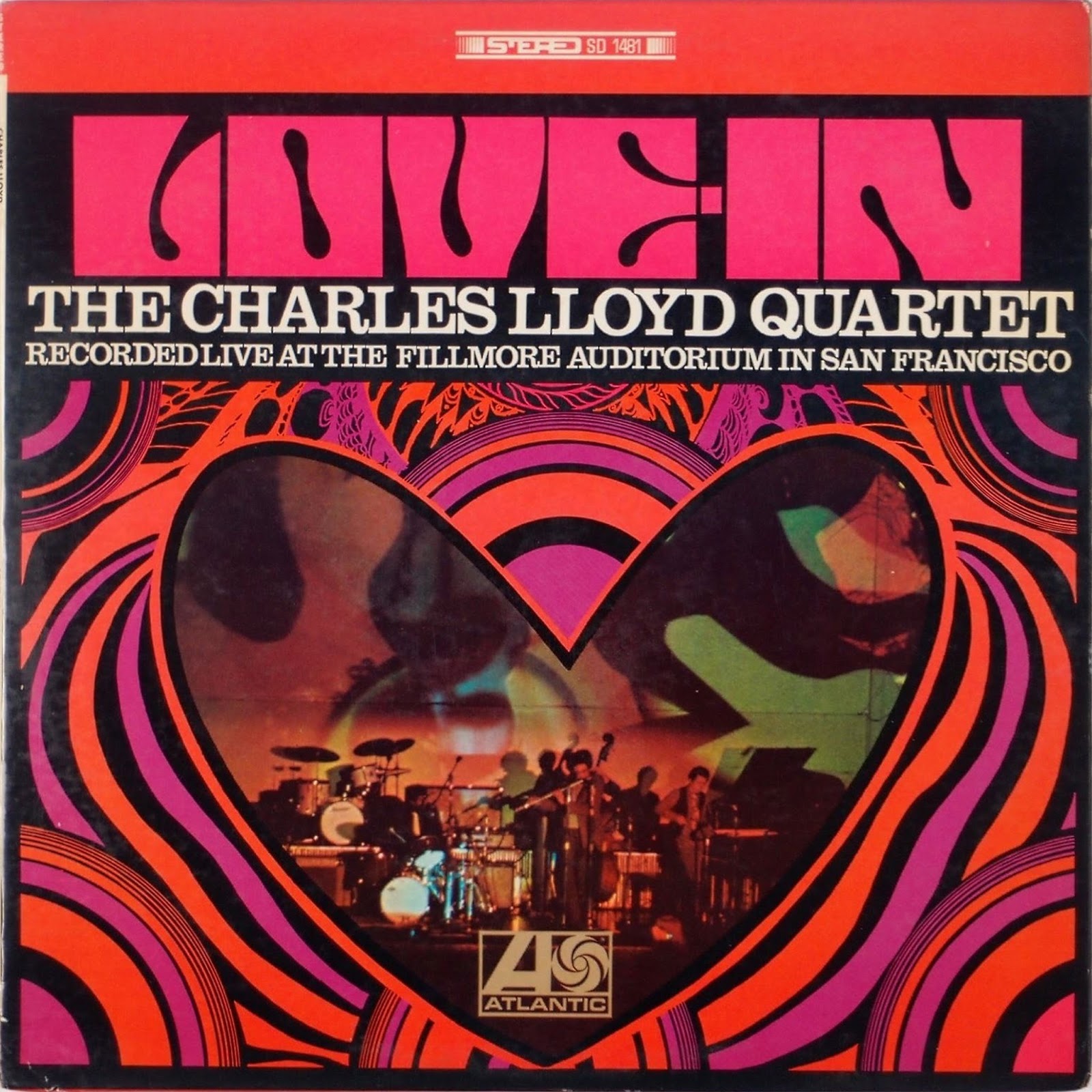

Miles Davis stole Charles Lloyd’s band, and much else. It was Lloyd’s classic quartet with Keith Jarrett on piano, drummer Jack DeJohnette and bassist Cecil McBee, not Miles, who were the first jazz act to play San Francisco’s Fillmore and gain an avid rock audience; their album Forest Flower: Live In Monterey (1967) sold a million, making Lloyd, with his Afro and hippie threads and exploratory, spiritually balmy sound a star. Playing acoustically, he built jazz’s bridge to rock, only for Miles to lure Jarrett and DeJohnette away, and Lloyd himself to seemingly vanish into the Californian mountains for almost 20 years.

And that is just one small part of a saga in which Lloyd has been a sort of jazz Zelig, placed by his talent and nature beside a cavalcade of 20th century icons, right from the day he looked out from the stage in Memphis and saw the truck driver Elvis Presley taking notes.

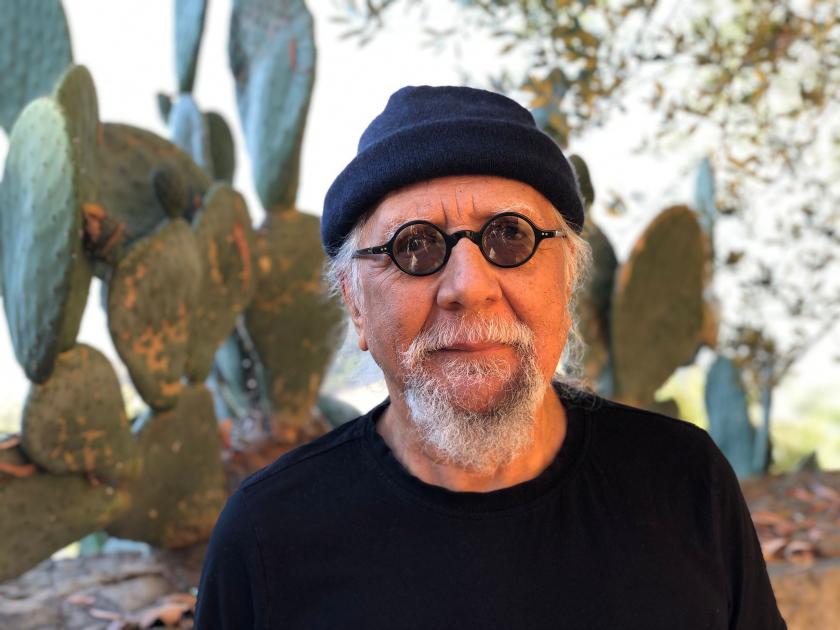

Lloyd is back out on the road, aged 83, after Covid cancelled last year’s plans, playing London’s Barbican tonight as part of the London Jazz Festival, supported by Nubya Garcia’s band Nerija. When he speaks to The Arts Desk via Zoom, Lloyd, with his white beard and beanie hat, is sitting atop his home on a mountain near Santa Barbara, further mountains and the Pacific filling its wraparound windows. His wife and co-producer, the painter Dorothy Darr, wanders through as we talk.

In his Memphis teens, Lloyd played sax with Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King and Muddy Waters. Then he left for cosmopolitan climes, studying classical music and clubbing with Ornette Coleman in Los Angeles in 1956, then fetching up in New York in 1960, aged 22 and already writing whole albums for Chico Hamilton. Even during his apparent vanishing, he played on his friends the Beach Boys’ “Feel Flows”, and with Beat poets in Big Sur.

In his Memphis teens, Lloyd played sax with Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King and Muddy Waters. Then he left for cosmopolitan climes, studying classical music and clubbing with Ornette Coleman in Los Angeles in 1956, then fetching up in New York in 1960, aged 22 and already writing whole albums for Chico Hamilton. Even during his apparent vanishing, he played on his friends the Beach Boys’ “Feel Flows”, and with Beat poets in Big Sur.

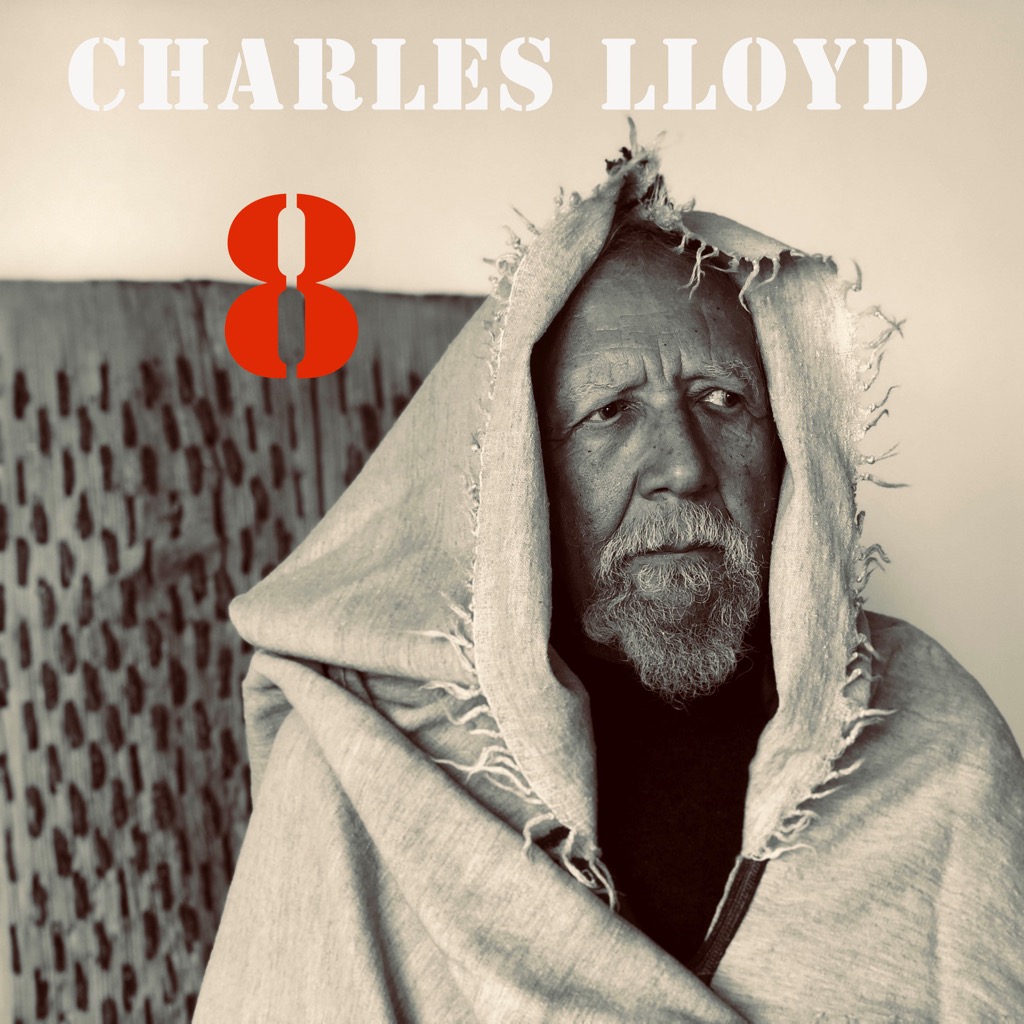

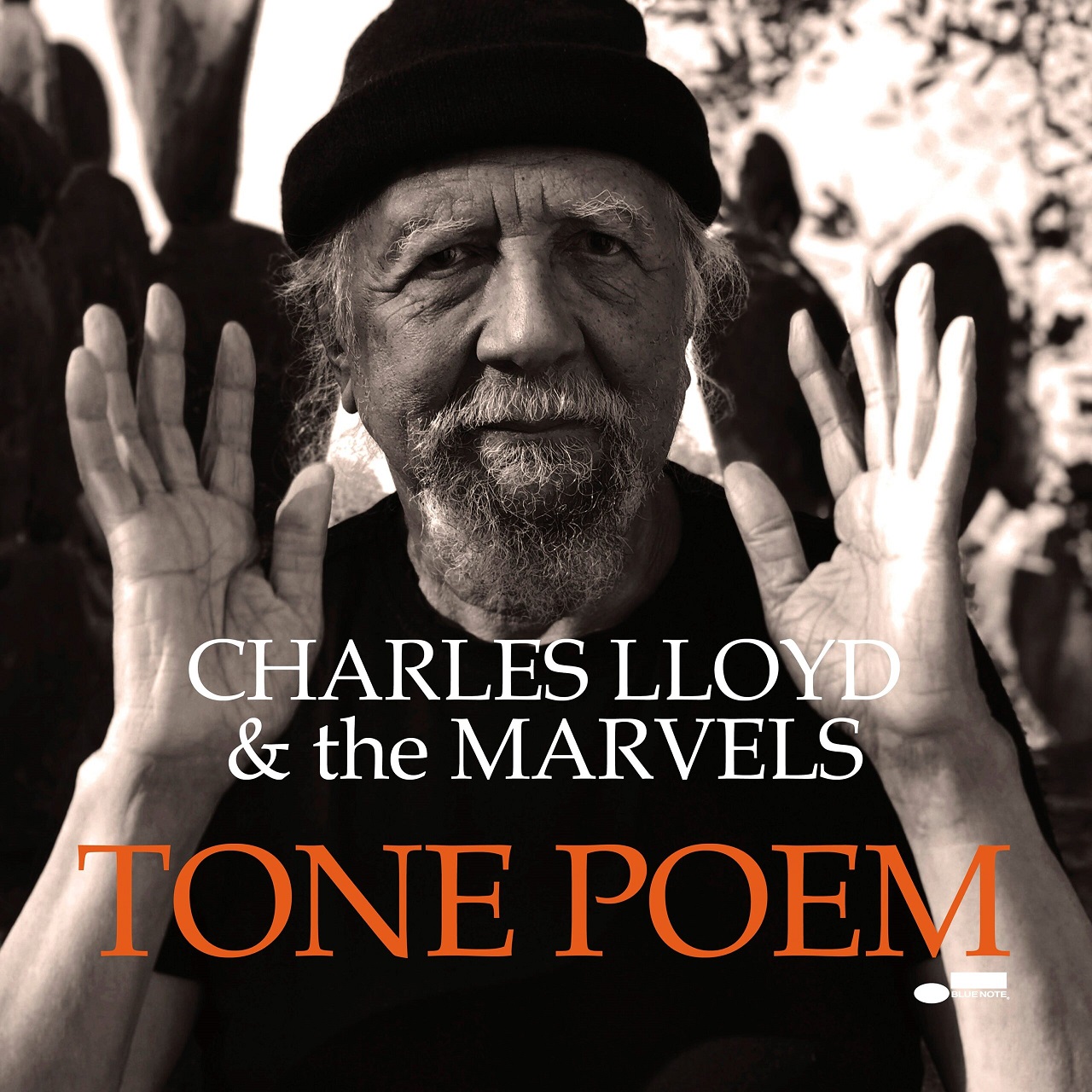

With tone and talent deepened by his time in the wilderness, Lloyd signed with ECM Records in 1989, recording prolifically. His more recent records on Blue Note are beautiful. You can hear him lean into his Memphis roots when playing with Booker T on the live triple-album 8: Kindred Spirits (2020), and on Vanished Gardens (2018), with Lucinda Williams; while the gorgeous jazz Americana of I Long To See You (2016) is steeped in folk verities, with guests Willie Nelson and Norah Jones. This year’s Tone Poem distils it all into music as limpid as his home’s mountain air. It’s just been named Jazzwise magazine’s album of the year.

“Do I seem old to you?” Charles Lloyd wonders. Gnomically spiritual, impish but not without edge, like his records he in fact seems in his prime. “How can we serve our mission?” he further enquires as we start.

NICK HASTED: I wondered how it’s been for you not playing – at least in public?

CHARLES LLOYD: Well, that’s a weird question. Because I am music, so I’m always playing. I love humanity. And I’m in service, it’s my life. As for travel, I wasn’t so reckless for my well-being, to go out in the middle of all that [Covid] stuff. I love solitude. I thrive in it. My wife’s an artist, and I’m a composer. And we’re in a whole world. I make music, I swim in the water and hike in the mountains here, and go out to sea. I’m at a different stage in life, you know. I’m not bar-hopping. I’m not on a cheap date! I’m in the skybox here, up overlooking the sea. It’s my think-tank, where I meditate sometimes.

When did you start meditating?

I started meditating formally in ‘66, ‘67, somewhere around there. A teacher from India initiated me. It’s been wonderful for me because it cultures the nervous system and fires me up to keep going. I’m always drunk with music, so it helps me to have some modicum of balance.

There’s a quote I love on your album Soundtrack (1969): “I want to transform things and make this a blissful place. I dream of the day when man can live in harmony. There’s still all that ugliness out there and I want to wipe it out with beauty...” That’s how it feels in your gigs. It is similar for you, when you’re playing?

Yeah, I go all in. It’s like there’s a chasm, before I play I always have a case of nerves. I don’t know if I can do this. Then once I get started, Dorothy’s trying to get me off the stage. Music’s in that other dimension. It goes out into the air.

You started off playing blues in Memphis. What was Howlin’ Wolf, pictured right, like as a bandleader?

You started off playing blues in Memphis. What was Howlin’ Wolf, pictured right, like as a bandleader?

Oh, he was a big man. He was a towering guy. Memphis has the Mississippi river, and then there’s Arkansas, Mississippi and Tennessee. So we were always going down there to those little rural places to play. It was strange and wonderful for me, because I was just starting. But I found he was very charismatic and powerful. He was a real source guy. And I also played with other guys like Bobby “Blue” Bland and Junior Parker, BB King – that was a beautiful place, Memphis, in terms of musicality. And this genius Phineas Newborn was my mentor, he started me out. They would frighten me, though. I’m remembering Bobby “Blue” Bland telling me that “Peaches” was his theme song, and if I messed up, he was gonna whip my ass. And I was just a little boy. It was a source spot, Memphis. Still is. And I imbibed that. It’s in my music. Because those elixirs were permeating the environment. And then I loved Billie Holiday and Lester Young and all of that, you know. But Bird [Charlie Parker, pictured below left, really set me free, because I had these images of him flying through Manhattan, blessing the whole thing. So the spiritual path was laid out there. Because I heard it in the music. Bird had the blues too, you know. Bird was conceived in Memphis.

Hearing people like that on the radio as a child, with your child’s saxophone to hand, was that music calling to you, even then?

Hearing people like that on the radio as a child, with your child’s saxophone to hand, was that music calling to you, even then?

Yes. It’s always been there. In this lifetime. I knew very early. I couldn’t get my parents to get me an instrument till I was nine, but I was trying to sing before that. I didn’t have the voice for it.

You’ve said “Memphis was a strange place to be born...”

It was. Well, I’m thinking of JS Bach, and that had I been born in Vienna, I’d probably have played the cello. What was strange was the set-up of America and racism, and the game that was run on people. And we saw that - my parents, everybody was hip to what was going on, what the gig was. However, it didn’t impede our playing. We were blessed as young people to know that although the place and the set-up was strange, the research and intensive playing that we were going through was magical. Because Jimmy Lunceford had started the music programme at my high school, and my cousin, who had turned me on to Bird and Prez and Duke Ellington, became principle of that school. And Elvis would come in and he’d be watching Calvin Newborn play. And I played with Big Mama Thornton. Elvis came round and recorded her “Hound Dog”. I played with all these people. I came through Memphis at a time when there were a lot of geniuses. The elixirs were pregnant.

But why a strange place to be born?

I’m thinking New York and Paris and London [would make more sense]. I’m thinking cosmopolitan places. But I was blessed because those bands like Duke’s and Count Basie would all come through Memphis, so I got to meet them and hear them. A melting pot, that’s what it was. I had my Choctaw great-grandmother Sally Sunflower Whitecloud’s Indigenous songs. She refused to walk on the Trail of Tears, and she married my great-grandfather, Ben Ingram Sr. So there’s a lot of research, and a lot of depth, and the tragedy of the history – not just in this country. You look around the world, and Caesar don’t love the people. We knew that the music was a sanctuary and spiritual uplift at the beginning, and continues so.

It makes me think of Billy Strayhorn, pictured above, Mingus and Nina Simone, who were all displaced from classical careers.

It makes me think of Billy Strayhorn, pictured above, Mingus and Nina Simone, who were all displaced from classical careers.

Wherever the creator drops us off, we must make the best of that. Billy Strayhorn was close to my heart. I record his pieces from time to time. He was in Pittsburgh at a soda fountain. He had these dreams, and this possession of the music. Strayhorn had classical music, he had all that, he was that. Just like those cats like Horowitz, the pianist, when he heard Art Tatum.

With that Choctaw and other backgrounds, and the melting pot of Memphis, you already had a lot inside you. But when went out into the world, did you gain a lot more?

Yeah, I’m always inquisitive wherever I go. I remember once we were playing in the Eastern Bloc, in the late Sixties with my quartet [released as 1970’s Charles Lloyd In The Soviet Union]. Somebody said to me, “How do you know our folk songs? You were playing them tonight.” Well, you open up, and with your individuality, you can hook up with universality. And it will take you to that place where we all meet. I’m striving in that. And I’m a...[searching for the right word]. What do you call someone who’s drawn to the ineffable? When I play music, I can go there. In the music, I’m found. It’s about the rapture. It comes in your heart, and it lifts you up and it also makes you a better person. See that’s the interesting thing also. The more I work on my character, to do no harm and like that, the better the tone gets. It’s like, “Oh, maybe Charles is ready for that now.”

Your first move was to California to study for a music degree at USC, digging into the modernity of Bartók, then playing jazz at night.

I was out here in California with Ornette [Coleman], and Gerald Wilson had a big band I played in. Buddy Colette was a great mentor, to Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Billy Higgins, James Newton and myself. Then many of us moved from California to New York.

The Band’s Robbie Robertson has fond memories of your apartment in Greenwich Village, with its great hi-fi, and Third Floor Richard living above you with his Lebanese hash.

Well, it was school. I was there where all my heroes have been. And I walked those streets and I played the Village Vanguard and all those clubs. Yeah, I remember Robbie, Levon [Helm] and the Hawks [who became The Band]. I knew all those guys.

Had you gone to New York wanting a bohemian life?

Yeah. I was 22 when I first got to New York. I checked in to the Alvin Hotel, on 52nd Street just off Broadway, where Prez [Lester Hamilton] had died. Birdland was across the street, and I was blessed because my best high school friend Booker Little was playing down there. I told Booker I was staying across the street. He said, “No, you’re coming home with me.” And then later Frank Strozier, the alto player from Memphis, invited me to stay with him in the Village. I was playing with Chico Hamilton, I replaced Eric Dolphy. Things were very lean. But I was still so idealist drunk with music that I didn’t see that. But then I got this loft apartment in Greenwich Village. So I had that bohemian thing. I lived on Washington Square. It was very beautiful. Because the Vanguard, the Half Note and the Five Spot were all nearby. Then my friends from California, Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry and Scott LaFaro all moved to New York. So I got to know all the musicians in my lifetime. Coltrane, Miles...you know, Monk asked me to play with him. I told my manager, “Wow, tell him I’m there.” He said, just go to his apartment. But Monk’s a deity, and I was afraid to. I missed that opportunity, because Monk would have been a wonderful finishing school. But I had others.

In the late ‘60s, it seems like Miles gravitated to rock out of competitiveness with music that was selling more, and considered more current. With your Memphis background, was it more natural to move in that world?

In the late ‘60s, it seems like Miles gravitated to rock out of competitiveness with music that was selling more, and considered more current. With your Memphis background, was it more natural to move in that world?

Yeah, I was invited to play the Fillmore, before Miles had anything going. Miles was a very competitive guy. The cash register was ringing [for rock], and he had a huge lifestyle that he needed to endow! See, here’s the thing. I grew up with that music, Howlin’ Wolf and BB King and Muddy Waters, who were the spiritual fathers of [rock’n’roll]. When I played the Fillmore, Jimi Hendrix, the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane all wanted to be on the same programme with my group. I was in my early twenties, and so were they, Jerry Garcia and all those people. John Cipollina, the Quicksilver Messenger Service guitarist, was very knowledgeable about jazz, and he played on one of my records back then, when I was stirring up stuff. As did Robbie [Robertson], as did Dave Mason from your country. I remember Janis Joplin was always coming around, she wanted to sing with us, I thought she was kidding (Joplin's debut album with Big Brother and the Holding Company, Cheap Thrills, is pictured below). And then later on, she wanted to sing “Summertime”. But I never would entertain that, because I didn’t wanna be known as a guy who was trying to take advantage of a situation. I played with the Grateful Dead a couple of times, and people came out with me a couple of times. It was because of music. And then I recorded with Jack Bruce with Frank Zappa. I was playing at the Village Vanguard one night and he was recording at the studio down there. That stuff never saw the light of day. But we were just improvising. Frank Zappa was a very smart, special guy.

How about Hendrix – who was heading towards jazz near the end?

How about Hendrix – who was heading towards jazz near the end?

Hendrix was slated to record with me. But time ran out on us. Buddy Miles introduced us in New York. We’d been hearing about each other, and we had lots of hair. I had hair before anybody did, I don’t know what happened to it! It’s still here somewhere [Lloyd takes off his hat, and lets his long white hair down]. In Los Angeles, I saw every other person had an Afro like mine. I thought, “Jeez, I’d better change up.” But you know, I don’t have lines of demarcation. Creativity is such that the artist’s milieu is his brain. Some people have this thing that some guys are over here, and some over there, I was never like that. Because I’m not a racist. I don’t judge people. The game of racism has to do with one man stepping on another man. It’s an incorrect conclusion.

You were up at Big Pink when Dylan and the Hawks, who became The Band, were making the Basement Tapes, weren’t you?

Yeah, I was up there. They had some guys from India, the Bauls of Bengal. And Bob Dylan had a big old Victorian house on the side of a mountain. We were very good friends. I always loved Dylan. He had a really great insight back in the ‘60s: [sings] “I ain’t gonna work on Maggie’s Farm no more!” You know, you say this and you say that. But what you’re out for is exploitation. You can’t step on a man. Dylan and me had a good time.

I’ve seen both you and Dylan live quite a bit. You dance quite similarly...

Well [impatiently], I don’t know about that. But let me tell you, when I did that record Vanished Gardens with Lucinda Williams, where we recorded “Masters of War” – “Is your money that good?” - [Blue Note president] Don Was said that Dylan was up at his office, and Dylan wanted to have that record. I haven’t seen Dylan in years. We’re still connected, though. I know him, on a deep level.

Why did you move back to the West Coast?

Why did you move back to the West Coast?

All this fame happened at a very young age, and people were coming at me for different, wrong reasons sometimes. So I started medicating myself and then I realised, that wasn’t the right path. I had to heal myself. I couldn’t do it in New York. The drug-dealers were trying to find me, to keep my meds going, and I couldn’t get away. I had to go away into seclusion where no one could find me. So I came back to California, where I had gone to school. It’s three-dimensional here – you’ve got the sky and sea. I needed space, and I needed to heal. So I took a beach house out in Malibu, and I stayed there for a while, in a row of houses where Jane Fonda, Merle Oberon, Rod Steiger, the Bee Gees, and Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton lived. Then I went up to Big Sur, for more retreats.

The rest of the world thought you’d disappeared.

I was healing. It just happened I went into a cave and drank lemon water. And I was done with chasing the goldmines. I wasn’t like that. I never thought of music a profit motive. Then later, I had to support my family. But I was an idealist, and it was a Thoreau, Walden Pond kind of thing. Simple living and high thinking.

When you disappeared from the jazz world, you were also making high-profile music with the Beach Boys. Was that like a day-job?

When you disappeared from the jazz world, you were also making high-profile music with the Beach Boys. Was that like a day-job?

No, no. Some of them were into meditation, that’s how we met. When Mike Love came back from the Maharishi in India, he saw in Time magazine about my meditation. They were fans and friends, and they came around when I had been blackballed by Atlantic Records. I couldn’t record for anybody else, and I wouldn’t participate in the plantation system in the music industry. And the Beach Boys made their studio available to me. They said, “What do you need? We’re big fans of your music.” And Brian Wilson had a big mansion in Bel Air with a studio in the basement, and they had great toys. I recorded there. They didn’t bother me about money. And then they had some records and I played on songs like “Feel Flows”. So the friendship grew. I was in Big Sur, but I didn’t have economics. Then Mike Love invited me down to Santa Barbara, where he had a large compound on the beach, a very luxurious set-up with many houses. He gave me a cliff house, and he had a studio there. I was blessed. And then Mike didn’t want to go out any more with the Beach Boys. He said, he’d go out if I did. So I went out [touring] to keep him company. They endowed my creativity for a long time. It wasn’t a day-gig. It was just helping a friend. Then slowly, I came back to my own music. In Big Sur, the poets found me. I played with people like Charles Bukowski or Ken Kesey, Gary Snyder, with his beautiful singing voice. William Burroughs would come around sometimes. Lawrence Ferlinghetti and I were tight, and we did a lot of college dates together. Burgess Meredith the actor was a friend, and we toured Harvard and the colleges, where he would read Carlos Castaneda and spiritual, Vedanta stuff. I did eclectic stuff. Because I wasn’t welcome in the jazz community. Because the Atlantic situation had been harsh, because I wouldn’t play ball.

The story is that you chose to retreat to Big Sur. Is it truer to say you were cast out?

Yeah. If you don’t play ball, and dance to their tune...it’s life in America. There’s an old saying, when Gypsy, Roma people take a baby when he’s fresh-born, they lay him out on animal skin, with a violin on one side, and a bag of money on the other. And he if he reaches for the violin, he’s going to be a musician, if gold, he’s a thief. But every now and then, a baby grabs both – oh, he’s going to be the head of our royalty department! That’s why back in New York I had my own publishing company. I was able to get my loft, and function. So that was grace. And I still have my compositions. It’s very important to my wife. She does the business.

For all that you gained and learned in that time of exile, was it hard?

In some senses, because you don’t have economics. But you go deeper into yourself. And then sometimes you get blessed, like when Mike Love and the Beach Boys gave me a nest. And then I had a patron for some years, a friend from Big Sur who was an heiress. She loved my music and Dorothy’s paintings, and she helped us a lot. So although I wasn’t on the circuit, I was able to function. This heiress said to me one day, “You’re so sensitive, I don’t know how you can stand to go public in airplanes.” And oftentimes she would send me in her own planes. With the Beach Boys I was spoiled like that too, in their private jet, and cars to meet us on the tarmac to play the concert. So you’re insulated. But, because I grew up in the hard scrabble of Memphis, you must not be attached to the spotlight, or the ease of operations. And you must also have humility and realise that you’re drunk with the music, you’re not drunk with the banksters.

You came back to your own music for good in 1988, after a near fatal illness.

You came back to your own music for good in 1988, after a near fatal illness.

When I came back they said, “You have to get to the back of the line.” I said, “But I brought something.” When I went away, I developed some other skills that enhanced the music. Like character. But that’s about 10% of this stuff [in the music business]. I realised I’m not going the traditional music route. And slowly I found my way with people who could relate to me. When I had just come back, Columbia and others wanted me on their labels, but a friend, Keith Jarrett’s manager Steve Carr, said, “If you go to ECM, it’ll be the slow-burn, but it’ll be honest, and you can do what you want to.” I stayed over there for 25 years, and I made some wonderful music. Then 10 years or so ago, some problems were coming in with ECM. Don Was had been a fan since his youth, and wanted me to come to Blue Note. He was very appreciative of what I was doing, such that I can own my own catalogue, and do what I want. I loved the enlightenment of it. Because I always thought of the American system as being plunder and thievery. The slavery mentality. But the stuff I’m doing on Blue Note is my best yet. I’m more liberated to go wherever the music goes. Somebody told me that somebody at that past record company I worked with said, “What’s he doing with Willie Nelson and Norah Jones [on 2016’s I Long To See You]?” Well you know what, I had this Billy Preston song, “You Are So Beautiful”, and I heard Norah Jones’ voice. And Don said, “Okay.” Like that. If I say to Don, I want Dylan to sing with me, he’d ask Bob.

Your latest album Tone Poem seems to distil the essence of what you do.

Your latest album Tone Poem seems to distil the essence of what you do.

It’s unfolding. It’s coming through, the more I can work on myself, and simplify, and go deeper. And I have sandalwood forests available to me, they say, “Oh hi, welcome Charles.” I’ve gone past the goldmines. It keeps me young and in springtime. Ecstatic was the word I was looking for before. I’m an ecstatic. [Charles’ wife Dorothy comes in]. We met in 1968. We’ve been almost 25 years where we are now. She built this world for us. On a thin dime. But it’s still beautiful. [Lloyd’s tone turns confidential] See, here’s the other thing I’m trying to get across to you. I ain’t seen anybody come out of this alive yet. You remember that thing you saw on my record, way back then – “I want to make the world a blissful place?” I want to make the transition, in other words, the last breath...

When you came fully back to playing in the ‘80s, was your healing complete?

When you came fully back to playing in the ‘80s, was your healing complete?

Oh yeah. It’s an ongoing – on what level do you speak [grins], do you know what I’m saying? Because I was a pescatarian, then a vegetarian, a fruitarian, and I’d fast for long periods of time, 30, 40 days. And then I would hike up in the mountains, I weighed 134 lbs. Then I wanted to be a breatharian, because if you live in a rich enough environment where the air is pure, which I do here, in the country, you can live on it. Where I live here, it’s inaccessible, and I live on a mountaintop, looking over the sea. My realtor told me 50 years ago, “You don’t want to live on that mountain. That’s too far out of the Village.” I said, great. Because there’s that old blues song, [sings] “I’m gonna move way on the outskirts of town/Because I don’t want nobody messing around.” So I don’t have no problem living with myself. But if you desire knowledge, you have to find a teacher, and you have to find the mirror of your inadequacies. And when you do that, then you find – I’m not there. It’s a beautiful thing, man. And then, you get met. Bird, Prez, Lady Day – I sing to her. Strayhorn [he sings a fragment of a Strayhorn tune, wordlessly]. Oh, I just recorded one of his songs, for Geri Allen. And I did some of his stuff on ECM [including “Pretty Girl” on his 2012 album with Jason Moran, Hagar’s Song, where Strayhorn sits next to utterly beautiful, riverine takes on Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” and Brian Wilson’s “God Only Knows”]. I’m still young – do I seem like an old guy to you? (Lloyd as a boy, pictured above). But the sad thing is, I’m losing a lot of friends. They’re leaving town. Like the great Greek composer, Mikis Theodorakis [whose music Lloyd played with the Greek singer Maria Farantouri on Athens Concert (2012)], and [jazz promoter] George Wein, he was 95. And [radio broadcaster] Bill Schaap, who knows more about jazz than anyone. So it gets kind of lonely sometimes. And then I have my compadres, like [bandmates] Jason Moran and Eric Harley, Bill Frisell, and we’re on the path. People call us pilgrims, troubadours – like my song “Passin’ Thru”. What I’m saying is, I’m still diving deep for those pearls. And if you’re sincere, you’ll be met. It’s a law of the universe. I have another saying that I learned in all those decades away, when I lived in Big Sur. To our work, we have a right. The fruits may or may not come. And the other thing is, we come through here, we sing our song. Nobody knows us, then we’re gone.

- Charles Lloyd plays the EFG London Jazz Festival at the Barbican tonight, November 20.

- Read more New Music reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment