It's a season of retrospection for Bruce Springsteen. New light has been thrown on his pivotal 1978 album Darkness on the Edge of Town with the release of The Promise, a double CD of out-takes and unreleased songs, alongside an expanded box set of CDs and DVDs telling the Darkness story in sound and vision. A version of Thom Zimny's documentary about the making of the album, included in the boxed release, was shown in Imagine on BBC One. It's part of a sporadic programme of reassessment of key works from Springsteen's career, which has included a 30th-anniversary edition of Born to Run and live performances of complete albums by Bruce and the E Street Band.

In the early stages of his career, Springsteen was a reluctant interviewee who preferred to let his music and his spectacular live performances do the talking for him. However, with the passing decades (and an accompanying growth in self-confidence) he has grown far more loquacious, granting interviews sparingly but making sure that when he does talk, he gives you plenty to chew on. The interview below dates from April 1996, when Springsteen was in London giving solo performances in the wake of his 1995 album The Ghost of Tom Joad, a bleak and sobering set of songs concerned with such topics as illegal Mexican immigrants in California and working men crushed by America's industrial decline, with a side order of James L Cain-style songwriter-noir for a change of pace. It found Springsteen in the middle of a lengthy separation from his faithful E Street Band, with whom he had last recorded on 1984's Born in the USA, and whom he wouldn't rejoin until their 1999 reunion tour. Evidently Springsteen, now happily equipped with wife Patti Scialfa and three kids, felt he needed to explore his own space for a decade or two.

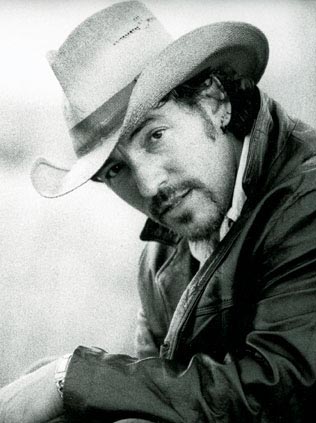

I still enjoy playing in clubs tremendously. When you play arenas, you're outside of town in some parking lotI spoke to him in a dressing room in the bowels of the Royal Albert Hall after one of his London shows, where he roved freely across the course of his career. Some of the discussion is inevitably specific to the Tom Joad material, but reading through it again I was struck by the way Springsteen's comments hold true for his artistic progress as a whole. It has been one of his trademarks that his personal evolution has been mirrored by gradual changes in his songwriting over the years, so that his new songs become “outgrowths of stories that I've written all along”, as he puts it. This theme of keeping the faith with his family and his background is one he addressed specifically in the Imagine film, citing it as a driving force behind the Darkness on the Edge of Town material and indeed on his work in general. In a surprising number of respects, the new Boss is the same as the old Boss.

ADAM SWEETING: The Ghost of Tom Joad feels rather like a book of short stories.

BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN: When I think about writing that way that’s sort of the form that I compare it to. When you have to cover something with just the words, I find that tremendously difficult. Because the music is so simple you can underestimate its importance, when actually it’s very, very important because… as I’ve said before, even though there’s only a few chords and it’s very intentionally sort of non-melodic and not intrusive, the rhythms are the rhythms of the character. The rhythms and where you’re pitched depends on the voice of that person; you can be lower or a little higher. Also you can use just a couple of bars of music to designate an enormous amount of time passing. Then in that space there’s all sorts of things that you can imply. That’s why you can tell the story of somebody’s entire life in a few minutes, literally three or four minutes. Or you can tell 100 years of history in four minutes - the music lets you do that. It creates a bit of a continuum, a space where those things are placed and that little musical distance between them can really denote an enormous passage of time, so the music is actually very important.

It’s songwriting, you know, but in the sense that there’s a geography to it, there’s a landscape, both a physical landscape and an emotional landscape where I’m trying to capture the essence of an individual’s life in some sense. What’s he striving for? What’s he struggling with? Where is he? The songs are very tactile in a sense. There’s a lot of detail and the emotional and the physical resonate off one another. Then there’s the sound picture, how I’m singing, which is very different on this tour than any other tour, because I don’t have to compete with a band. So I can sing very low, use a lot of different types of vocal inflections, and do things that I haven’t been able to do in the past.

You were using an interesting voice in "Adam Raised a Cain". It reminded me a bit of Richard Thompson.

You were using an interesting voice in "Adam Raised a Cain". It reminded me a bit of Richard Thompson.

Really? I did some of the riffing, now that you mention it. It’s using a lower part of the register in a slightly different vein.

There was something that sounded like Liverpool Irish in there too?

Oh really? That’s interesting. I didn’t realise that. I know what you mean, some of that sort of phrasing. A lot of that stuff, if you go back a long way, it’s from the English murder ballads and there’s a connection to that type of folk music.

You recently played some shows with Joe Grushecky [the Pittsburgh rock’n’roller with whom Springsteen had collaborated on the album American Babylon]. Why did you do that so shortly before your own tour?

I told him I would, y’know! When the dates came around at the time I said, “Oh gee, I wish I hadn’t committed to doing this,” but I had and I was glad that I did it, because I had a great time. It was a lot of fun for me to do and it was nice it was with a rock band. I knew my own shows were going to be acoustic, so it was a chance to blow out all the electric guitar playing, plus somebody else carries the show and I sang a little bit and played a little bit and enjoyed travelling around with the band [The Houserockers] which is something I like to do. And I like Joe, and his fellas are great. I liked playing in clubs, and it’s a different type of playing that I still enjoy tremendously. You feel a very integral part of those local communities at that level, you feel very connected. Once you start to play arenas, arenas are always outside of town, you’re in the middle of some parking lot, but the theatres and clubs are always in town, you’re in the middle of the city. Life is revolving around those places, they’re places where people gather. I just like going into those towns and feeling a part of that.

Despite the serious tone of these concerts, you also manage to introduce some humour. You’ve been playing a comic song about Santa Claus, and on the last tour in 1992 you were doing a kind of Burt Lancaster/Elmer Gantry routine?

There’s a novelty album in me somewhere waiting to come out. Ha! I’m actually the Alan Sherman – nobody will remember this reference – but I’m the Alan Sherman of my generation. Actually last night was the first time I played the Santa song. I only wrote it last week or something. It was just for fun, y’know. It’s a counterpoint to the other material, I try to balance the night through some of the speaking and some of that type of material. Plus it’s fun, the audience gets a kick out of it. Me too. And with those type of songs it’s like everybody’s been there. Or if you haven’t, you’ve still been there! So everybody knows what you’re talking about.

The Tom Joad songs talk about subjects like Mexicans making amphetamines [“Sinaloa Cowboys”] and young kids forced into drug-running and prostitution [“Balboa Park”]. I’m assuming these aren’t from personal experience. How did you go about researching the subject matter?

Probably since the late Eighties I’ve travelled a lot in the Southwest. There’s a couple of friends of mine who come along, and the feeling of the geography came out of those trips. Since the mid-Seventies I fell in love with the Southwest in general, the desert, and we’ll go for 1000 miles or 2000 miles over the course of a week or two and we stay off the Interstates [highways]. It’s just local state roads and it’s a very different life. If you go on the state roads, 1940s America still exists, y’know, it just doesn’t exist on the turnpike or the Interstate. There are no franchises because there’s not enough people so they don’t put them there. You can go for enormous stretches, maybe 100 miles, and hit very small towns, these little four-corner desert towns. I always found there was something I liked about it. I Iike the weather and I like that part of the country and the sense of space, so the geography of that music probably had its seed in those trips. I still get out there when I can.

Probably since the late Eighties I’ve travelled a lot in the Southwest. There’s a couple of friends of mine who come along, and the feeling of the geography came out of those trips. Since the mid-Seventies I fell in love with the Southwest in general, the desert, and we’ll go for 1000 miles or 2000 miles over the course of a week or two and we stay off the Interstates [highways]. It’s just local state roads and it’s a very different life. If you go on the state roads, 1940s America still exists, y’know, it just doesn’t exist on the turnpike or the Interstate. There are no franchises because there’s not enough people so they don’t put them there. You can go for enormous stretches, maybe 100 miles, and hit very small towns, these little four-corner desert towns. I always found there was something I liked about it. I Iike the weather and I like that part of the country and the sense of space, so the geography of that music probably had its seed in those trips. I still get out there when I can.

Then after that, in the songs there’s a lot of border reporting in California in general. The immigration issue has become a political football this year, but those are stories and issues which in southern California have been issues always. You see a lot of that. I’ve been up through the Central Valley, my parents live up in northern California so I’ve made those trips quite a few times. I’ve probably been around California more than I have been New Jersey really. It’s funny, when you grow up someplace you stay in your one little area, but I guess the songs come from a lot of different places. “Sinaloa Cowboys” was a fellow that I met and just his voice, there was just something about it that stayed with me. This idea of these two brothers stayed with me.

Watch Springsteen perform "The Ghost of Tom Joad"

Then I think I read an article on the central California drug trade and basically that’s how a story sort of comes together. You’re telling a story about a family, something that everybody understands - a certain type of familial loss is something everybody understands. And you place it with these other considerations. If you were making $4000 a year and somebody said you could make $10,000 in a night, what would you do, y’know? What would you do?

Those are the questions I like to raise. If you go up through the Central Valley now, in the 1930s you had the Okies, now there’s Mexican Indians. A lot of very similar stories, just the skin colour’s different. People come across that border every single day and risk their lives, cross the rivers and the desert. What’s that about? To me that is just an interesting subject. It felt like that was a subject that I’ve tried to address in different ways in the past. They aren’t just American issues because you see mirrors of then in Europe and around the world. So songs come from a lot of different places (Springsteen samples European brew, pictured below).

Sometimes it’ll be from something I’ve read or something I’ve seen, but in the end to make them work you have to find the part of you that’s them to make it real. If you don’t pull something out of yourself, some real part of yourself, the song’s gonna ring false. That’s the key to any type of writing. To earn those subjects, you’ve got to dig into yourself. If you do that well, you have a good song. If not, you have a song that rings false or is not a good song. At this point in my work, that’s what interesting to me.

When you became the biggest star on the planet after Born in the USA, did that cut you off from some of the things that made you want to be a songwriter in first place?

Well, I’ve always held to the belief that isolation is a personal choice. Wherever you find it it’s a personal choice. If you come home from work and you’ve got your two six-packs of beer and your television set… I’ve seen plenty of people as isolated as people would assume whatever the wealthiest people in the world might be, or this rock star or that rock star. I’ve seen it. I grew up with people that lived in that kind of isolation, so I never saw it as a fundamental or necessary result of the experience that I’ve had. I think when that happens there’s some certain amount of bullshit that you have to be ready to navigate and negotiate, and it’s not worth giving up your freedom. Basically throughout my whole working life I’ve pretty much done what I’ve wanted to do. It might be that you maybe go to the movies on Wednesday night instead of Saturday, those types of choices, or if you don’t feel like it that night you don’t go out. You’ve got to be ready for people to come up and say hi and you say hi back, I don’t mind that most of the time. If I’m with my family or something I don’t like to be intruded upon, I’m very protective of that. If I’m with my kids I don’t sign any autographs or anything, that’s their time, but otherwise it’s fine if people come up and say hi, how you doing.

Right now for me it’s very manageable. I’m not that person at this point, y’know, whoever that was [ie the mid-1980s superstar]. Some part of it’s always there but really what I’m doing now is… in the States certainly the Tom Joad album was out of the mainstream. The audience that is coming to my shows is a very dedicated audience, and has probably followed me for quite a while and has a sense of the history of my work. To come for this type of show it has to be an audience that’s committed to your music and your ideas, because it demands quite a bit from them over the course of the evening. It’s a very satisfying experience for me. People really collaborating with you, because the material can be rough going or something, I suppose. But for me it’s been very rewarding, and I hope it has been for them.

Right now for me it’s very manageable. I’m not that person at this point, y’know, whoever that was [ie the mid-1980s superstar]. Some part of it’s always there but really what I’m doing now is… in the States certainly the Tom Joad album was out of the mainstream. The audience that is coming to my shows is a very dedicated audience, and has probably followed me for quite a while and has a sense of the history of my work. To come for this type of show it has to be an audience that’s committed to your music and your ideas, because it demands quite a bit from them over the course of the evening. It’s a very satisfying experience for me. People really collaborating with you, because the material can be rough going or something, I suppose. But for me it’s been very rewarding, and I hope it has been for them.

Born in the USA in one sense took you away from where you’d been as an artist before, but also gave you the freedom to do what you do now?

It was sort of an anomaly. It was a funny sort of blip on the screen. I knew when I wrote the song "Born in the USA" that it felt powerful and I knew it would be popular or well received or whatever, but I didn’t expect that particular type of experience. But I’d been around for a while and I sort of rolled with it and enjoyed myself, and for the most part it was something I’m very thankful for. It’s contributed an enormous amount to my life and it has allowed me to have a certain kind of life and a lack of financial worries that most people never have, so in that sense it was something I really enjoyed. I felt we did a very good job at that particular point in time in trying to remain as focused as I could on what I was doing. But it wasn’t something I was expecting to do forever or would have wanted to do forever. I recorded Tunnel of Love next and that was my adieu to that whole particular part of my life and my work, and that’s fine. I wouldn’t want to live in that particular place for my whole life. I wouldn’t want to be somebody who has to. Right now I’m very comfortable.

Tunnel of Love was about your first marriage to Julianne Phillips [the couple married in 1985 and were divorced in 1989]. How do you think of that now? Was it a mistake, or something that looked right at the time and just turned out wrong?

Well, my first wife was a great gal. She’s a very lovely woman and I wasn’t really ready to… I didn’t have the flexibility to really know how to do that then. That was something I had to learn, y’know. I think people expect those types of things to just come their way, but like you learn your job, it may have to be something that you need to work on and learn. So in that sense I look back on it and I certainly don’t regret being married. I think you always regret a divorce, but it was a part of just moving along, and it’s enabled me to have the family life that I have now and the relationship that I have now. It’s just part of living really.

It’s hard for me to judge, but you seem to have found a freedom now you didn’t have a few years ago?

It’s hard for me to judge, but you seem to have found a freedom now you didn’t have a few years ago?

Well, what I’ve got now is a great thing. In the sense that I get to come out on stage – I’ve said it before – I don’t have to play myself, I get to be myself at night. I have an audience that comes and gives me that freedom, and then in turn I can give them what I feel is my best right now. I live in the present. The show is new music for the most part, or if I do something that’s from the past it’s almost always radically rearranged. I usually don’t do "No Surrender", but tonight hey, you know, I took a swing at it, but for the most part… I don’t really need to sell a million records or two million records, but I do need to feel like my work is vital and that I feel motivated to walk out on that stage.

I just feel like me. I don’t feel caught under whatever that particular iconic thing was in the mid-Eighties, I suppose I feel a certain freedom from that right now. It’s the box you build, but that’s what performers do. A lot of your job is performing in public. You build a box and you’re supposed to be Houdini, you’re supposed to slip out of it and appear over there in some fashion. Which is in a funny way what people do in their normal lives. You’re always asked to extend yourself and to reinvent yourself and to renew yourself. People have to do that in life so of course you have to do it in music and in your work too. It’s a part of the living process instead of part of the dying process.

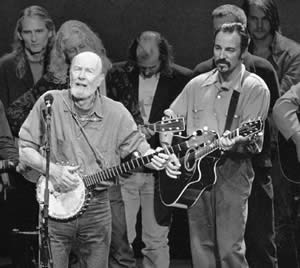

“He not busy being born is busy dying,” as Bob Dylan put it? (Springsteen and Dylan, pictured below)

Yes, otherwise all of a sudden you’re caught in the shadow or the echo of something from a particular moment you’ve had. I played with the E Street Band band about a year ago, and it was fun to come out and kick through the tunes, and I’d love to play with the band again at some point. But for me right now, there is a lot of freedom in this particular tour. Before I did the Tom Joad record and before we put it out I knew it was probably not a mainstream record, and that it was a record that was going to fight to be heard, certainly in the States. It has found a more receptive audience here in Europe. But that was OK, that doesn’t bother me. I think for me right now that sense of being able to walk out onstage and not have to play this one or that one…

Or have to be The Boss?

Or have to be The Boss?

Yeah, The Boss, exactly. That’s pretty lucky, because most people that far into a career can get caught in that rut pretty easy. I remember the first night I came onstage I said man, that felt good, you know? I just felt sort of yeah, that’s lucky. I had this group of material that I get tremendous pleasure out of performing at night. That feels like a real integral part of me and a part of my present. Whatever the emotional issues in the songs are, it just feels very sort of fresh for me, so I’m enjoying it tremendously.

If you had never met your producer and manager Jon Landau, have you any idea what your career would have been like?

I don’t know. Its possible it may have been more like this. I don’t really know, you know. It may have been, it may not have been. I was always ambitious and I don’t believe you just fall into that sort of fortune or fame - you chase it. Some part of you chases it even if some part of you runs away from it. I was very interested in pop culture and what you could achieve at that level. Did you have to destroy yourself? Did you automatically betray your ideals in some fashion, and then what did that mean? For the health of your spirit or whatever, what was driving you? You don’t know those things when you start. You think you know, but you don’t really know. So you go into it and you just sort of try to find out those answers, I think.

So with Jon, I guess he’s my partner in the sense that if I say… I don’t know if he’d see it like this, but he pushed me towards the mainstream a little bit more than I might have done on my own. But I don’t know. I don't really know. It’s impossible to tell, y’know. Because very often I would transfer onto Jon the decisions that I wanted to make but didn’t want the responsibility for [laughter], so it became his decision or his influence when really it was just sort of… we were collaborating and it was some part of me that I didn’t want to ‘fess up to, that hey, maybe I wanted that more than I thought I did.

It’s impossible to sit and pull the thing apart at this point, but he’s been, outside of being one of my very very deepest and best friends, his contribution to my life in general has been enormous. He’s just very influential and it’s just the old story of your good friends that talks, just stuff like that. We sat for hours, throwing around our theories about music and what are we doing? What are we trying to do? What do we want to do? What should we do? What shouldn’t we do? For me we were sort of the optimum creative relationship, in a sense. Also having someone you can completely trust is a great luxury, as most artists will tell you. His friendship has been very important for me.

Do you argue with him? Would you have argued about putting out an album like Nebraska [a very minimal and lo-fi record], for example?

Er… do we argue directly… I dunno, we tend to be pretty indirect, but we end up throwing things around. We didn’t argue about putting out Nebraska.

Or about Tom Joad?

No. I think if I come up with something that I feel really committed to, if he has some reservations he’ll express them in some fashion, or he’ll just say well, this is great, but this is gonna be our circumstances when we do this. I can’t think of any particular record that one of us thought should be released and one of us thought should not. In the end it’s my music and it’s my work and I take my own risks. I guess I’ll filter some of the things through him and get his opinion and then see, as I do probably do say with [recording engineer/producer] Charlie Plotkin, somebody who’s worked with me for a long time, and a few of the other people. That’s sort of the way it works. It’s funny because it works pretty seamlessly, it works in some very natural fashion. All these things get sorted out in a very non-obvious sort of way. It’s interesting, I can’t quite explain it, y’know, but it’s probably been part of the key to the relationship. When we got together things just worked, and it felt very natural (Springsteen performing with folk-music icon Pete Seeger, pictured below).

Jon Landau and Dave Marsh [rock critic and Bruce’s biographer] were from a particular generation of major influential rock critics. Do you feel those sort of people are still around? Can you have the sort of dialogue now you would have had with them?

Jon Landau and Dave Marsh [rock critic and Bruce’s biographer] were from a particular generation of major influential rock critics. Do you feel those sort of people are still around? Can you have the sort of dialogue now you would have had with them?

Oh, there’s intelligent people writing out there. It’s just like the music, it's like everything. There’s probably a handful of good people that are really sort of engaging, and then there’s a lot of stuff that just comes out, you know? [laughter] I was aware that Jon was a writer, I’d read some of his writings, but our relationship wasn’t really based on that particular part of his work. We got together because I was making a record and it wasn’t working out. He was a producer at the time, he’d produced the MC5 and I think Livingston Taylor [younger brother of James Taylor], and I needed a producer, so he came on as a producer basically. Then we had sort of your classic - I would guess - musical friendship, your buddy you get together with and say, "Hey, did you hear this?" That turned into production where we started to work together because there wasn’t really anybody else that we were that happy with, and then it ended up becoming the management thing, which was the last and sort of a pragmatic development. But it started off as basically a personal relationship about ideas. About what pop music could accomplish, the type of feeling and experience that I’d had through music and that he had also had.

We had something in common there, that we’d both at some point been deeply moved and had our lives changed by pop music. Music that people thought was junk. If I had an opportunity, I wanted to try and have that same sort of impact on my fans if I could. That was something I strove for, and also the idea that the form itself was somewhat unlimited. It could take on a lot of different topics. Spiritual ideas, political ideas. You could have a three-ring circus and it could all work together, be a dance party, and it wasn’t contradictory. It was just an expression of life and a view of the world. Of the things that people need and want to get by, desires, hopes, y’know. Tragedies. That’s sort of the approach I’ve taken since I started and ever since. That’s how I’ve basically lived it and at night when I come out even with this show, that’s what I’m trying to get across to you - this is where I’ve been, these are the things that I’ve seen. So you’re trying to present to the audience a pretty big emotional picture (Springsteen rocks London's Hyde Park in 2009, pictured below).

You once said that the danger of fame is in forgetting where you came from.

You once said that the danger of fame is in forgetting where you came from.

I always believed that the value of what I did was in its value to my audience. My connection to that audience was through the way that I performed my job on a given night, that was how I showed respect for my audience. I think I was lucky in that I was surrounded by people that I had known and some who I had grown up with for a long time, and they were always a touchstone and I found that very helpful. Also I felt to continue to have things to write about, you had to have your feet reasonably close to the ground, and that all of those things over a long period of time would amount to the cumulative value of your work. The longer you were able to perform that job in that fashion, your work would accumulate a history and a power that would increase its meaning in your audience’s life, as years passed. Songs can get better, they can get better as time passes. So those ideas were a very integral part of what I wanted to do aesthetically, and also what I wanted to be, just the person that I wanted to be, what I wanted to be about.

Essential to that idea I suppose is remembering what those things are that make you tick, make you alive, make you valuable, make you useful. The things that really matter. Because once you step into the music business there are so many other things, all of which are seductive, and may seduce you from time to time – you may go over here or go over there or get lost somewhere. Everybody's got a right to get lost, it happens. You can drift this way or that way or make bad decisions, that’s just a part of living, but hopefully you’ll have that anchor that eventually will… I found over a long period of time I had that anchor somewhere in me internally, but I also had it with the people that were around me. I had very intelligent and thoughtful and caring people, y'know, Jon Landau, my wife Patti, the E Street Band, Barbara Carr [his co-manager]. They’re professionals, and my idea was you could come to our show, where professionalism is not a dirty word. I found that in that code or whatever you might want to call it, there was stability and value that in no way denigrated your spontaneity, authenticity, or approach to the way that you did your job, so that was the idea. I guess that’s what I was alluding to whenever I made that particular statement.

You’ve had your songs included in a couple of movies, including Philadelphia and Dead Man Walking. Was that an attempt at reaching out in a slightly different way?

It just happened by accident. Jonathan Demme called me up and said he needed a song for Philadelphia. I knew him and I respected his work and I knew what the picture was about. I didn’t read the script or know anything about the film itself, but I knew that it was going to be a big Hollywood picture that dealt with Aids and there hadn’t been one really yet, so that was an opportunity. A song plays a very small part in anything, but it was an opportunity to kind of put my two cents in. So basically I wrote the song in a few days and sent it to him.

A similar thing happened when I did a song for this movie The Crossing Guard with Jack Nicholson and Sean Penn. I’ve known Sean a while and his pictures are always intense. I saw the movie and I loved it, I came out and said wow! I thought it was great. The kind of picture that doesn’t get made in America very much any more. So he said he needed a song at a certain spot, somebody else had pulled out, so I had a few things I thought he might like. And then with Dead Man Walking, I’ve met Tim Robbins a few times and he said he was making that picture and do I have a song. So it’s just really through meeting somebody and then saying if I had something or if I could come up with something I’d pass it on. But it’s pretty tangential. Tim did a good job. He worked very hard at making a record. He contacted the artists and he had a theme and he was very interested in producing a record that held together as more than just a movie soundtrack.

I was reading somwhere, in the NME I think, about you having therapy.

I have at different times, yeah.

I have at different times, yeah.

For a particular reason, or just for a kind of general psychological spring-cleaning?

Just basically to search for more freedom. I was getting into my thirties and I was interested in having a family and I simply wasn’t flexible enough to do that. I’d lived a somewhat solitary and one-track existence, because that’s what came naturally to me. The world that I created was very sort of insular, and I said I’m going to lose that because you can’t... it just isn’t going to work, y’know. I had the tendency to get very emotionally isolated, not necessarily physically. To just sort of slip into this deep well of some sort of emotional isolation. I guess there was a point where it got very deep, and that was when I said "hmm." I just felt very detached from things and that wasn’t how I wanted to live my life, but it may be why I have a good feeling for those types of characters. Whether it’s “Straight Time” [from Tom Joad], or people that are sort of struggling with that idea. That’s just something that’s always come pretty naturally to me, so I’ve had to work to sort of… how can I put it…? The type of flexibility that you need to have a relationship with somebody, I worked pretty hard for that. And it’s OK, it worked out! It’s been working pretty well, you know, so… initially I went to therapy just sort of generally, just like hey, and then you find your way through the problems. It’s just like I worked at the guitar for 10 or 15 years before I felt I’d begun to get a handle on it. Why people think they don’t have to work on anything else, that it’s just going to come natural, I don’t know. At some point I realised oh I get it, you’ve got to work on this and you’ve got to work on this too, oh! That’s why I’ve had bad relationships for 30 years, because I don’t know how to do that. I know plenty of people who weren’t able to make that transition. I had a few friends that were well into their sixties and were still struggling. There are people who don’t make it at all. It’s a certain type of character that gets romanticised pretty often in fiction, but I don’t know about living there constantly. So my life has sort of always been a struggle between those two things. That’s why I picked a guitar up, to communicate and to connect myself, because I was somebody that that didn’t come easy to.

When did this realisation dawn on you that you needed to make changes?

I was in my early thirties. Sort of when I’d had a good deal of whatever the rock’n’roll experience was at that point, and I realised that the things you think are just the way you are, at some point it’s like the ocean sort of washing away the surface and leaving the exposed rock. At some point the truth of those things starts to appear. As you get older time does that. Time washes away the things that you’ve used to cover your inadequacies, and when that happens, all of a sudden that bare rock is there, and for me that was my early thirties. So I started to try and get a handle on some of that stuff.

Does your song “Stolen Car” from The River deal with that sort of emotional state you’re talking about ?

Does your song “Stolen Car” from The River deal with that sort of emotional state you’re talking about ?

Yeah, in the sense that that was an early example of a certain type of psychological writing and a certain type of character that I’ve returned to quite often. Someone struggling against some sort of emotional isolation and lost in that particular void, that void that always feels like it can be waiting there. In fact it is always waiting there. That’s why you have to manifest your own faith and your own strength and your own belief in love, or whatever you want to call it. It takes strength to pull those things up out of you. So with a lot of my characters, beneath the circumstances of each song I think you’ll see a lot of them struggling with those ideas in one fashion or another. Which I think everybody does, basically. I think that’s a very common experience.

At the No Nukes concerts at Madison Square Garden in 1979, you sang "The River" onstage for the first time. In the video from those shows, you looked as if you were in an incredibly emotional state singing that song.

[Laughs] I probably was, yeah. That was a song that was very connected to my family. It was really based on my sister and her experience, and my brother-in-law, so it was a song that felt very very connected to my life, and our lives, and it was the first time I’d found that particular type of expression of it, I think. I think she might have been there that night too. Actually if you go back to that particular song, that’s really the prototype of the stuff I’m writing now. That sense of geography and place and basic issues and types of characters. Yeah, those opening two lines – “I come from down in the valley where mister when you’re young, they bring you up to do like your daddy done”, that’s it! You know, period. That’s what was set out for me, and for all of my friends and for everybody that I knew. And so being somebody who through one thing or another managed to slip that particular fate, that particular idea has probably motivated almost all of my work since then. That’s why I think these new songs fit, really. Why they pick up the threads of my past work. It’s about keeping a certain sort of faith with the legacy of my own family. I don’t come at things from a political point of view in the sense that I was never… we didn’t have a political household. Politics was just something that went on, that was happening, and it seemed very different.

Watch Springsteen and the E Street Band play "The River" at Madison Square Garden in 2008

What would your father have voted?

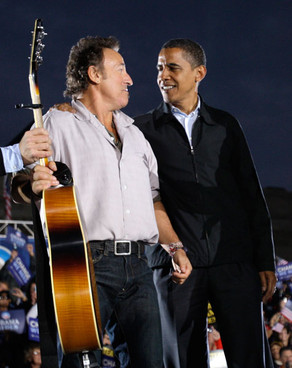

Oh, the only thing I remember was I came home from school one day, I asked, "Republicans or Democrats?" He says we’re Democrats because Democrats are for working people. That was the entire political education in my house, and that was it, we’re Democrats because they’re for the working people. For some reason I never forgot that. Whatever the political implications are in my work, they come up from the personal. They come up from some sense of fidelity towards my experience and my family’s experience, my mother’s life and my father’s life and my sister’s life, and I felt a need and a desire to give voice to those things. That was always very motivating for some reason, and it still is. I believe I’ll be writing basically about those things in some fashion for the rest of my life. That is my work, y’know, that’s what I do. I feel very at home in that particular setting. My own life has varied quite a bit, I’ve certainly lived beyond our wildest dreams when we were kids, but those things are at your core. It was something that I always returned to and I always felt very grounded in writing about those things. Maybe that’s why people respond to that particular part of my work (Springsteen the Democrat with President Obama, pictured below).

Have your wife and kids in a sense replaced the E Street Band?

Have your wife and kids in a sense replaced the E Street Band?

Well, you don’t replace them. There’s a moment when the band plays a familial role, they become your family. My family travelled to California when I was 19, so in those days there was no way to go see them or anything, we didn’t have the money, none of us had ever been on an airplane. My parents had never been on an airplane in their whole lives, and my dad was probably a little bit younger than I am now. I’ve told the story before, but they saved about three grand and they packed up the car and they slept two nights in the car and a night in a motel. Over the next period of years, to see them I had to drive across the country with a friend of mine.

I’d do it usually around Christmas time. We’d get an old car and take the southern route, and every year I’d drive out there a little bit if I could. The band were back home in New Jersey, where I stayed because I could support myself. I couldn’t support myself in California - I tried it a few times and you couldn’t get anybody to pay you to play. So because I had a reputation in my home town, I was able to make a living, so that’s why I stayed in New Jersey. So the band at that point yeah, they take on the family role too, but I think that then you grow out of that and you have a real family. In our case, because we spent so much time together, it’ll never just be the band. We have some sort of a bastard relationship. We’re friends, and we do feel like we’re related or feel some deep connection that would always be there if we never played another note together. There’s all the complications of family and we were together a very long time, and part of the reason was because we ended up getting along pretty well.

On some level everybody loves the other guy, whether you’re driving each other crazy at a given moment or not. Relationships like that are not simply categorised. Once you’ve had relationships that have lasted 20 or 30 years, there aren’t any boxes that you can put them in. They don’t exist in that kind of place. So I’ve been lucky. I play with people I love and that I still love and have deep feelings for, and I’ve been able to have the family that I wanted at a particular time. I’ve been able to not be destructive, or too destructive. I’ve been able to be creative, and hopefully to be entertaining and rewarding for my audience on some level. And I’ve been able to keep my feet planted in the present, so I’m a pretty lucky guy!

Add comment