theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Stéphane Denève | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Stéphane Denève

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Stéphane Denève

The Royal Scottish National Orchestra's beloved music director talks about Berlioz, working for Solti in Paris and losing consciousness

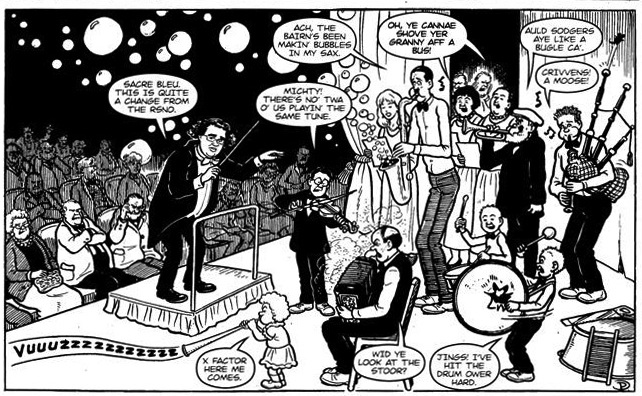

He's just launched the last of seven phenomenally successful seasons as music director of a transfigured Royal Scottish National Orchestra. Subscriptions for the Edinburgh and Glasgow concerts have doubled, attendances soared, and Stéphane Denève is a popular figure not just in the musical world but also in Scotland's wider cultural scene, not least as measured by his special guest appearance in the Sunday Post's long-running cartoon series The Broons.

The charm of his concert presentations to his Scottish chums belies a rigour and a seriousness in a preparation that marries intellect with sensuous sound quality, as I witnessed in last season's performances of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique. It was after the first of those that he spoke to me in his spacious, airy Glasgow town house.

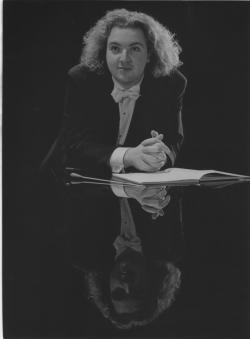

There was more sympathy than hilarity to begin with over the black eye I was sporting after having smashed into a post on my bike the day before. So RSNO communications manager Danny Pollitt took the snap pictured on the right, with the putative caption "conductor whops critic" (theartsdesk review of the concert, however, could hardly have been more favourable). Then I began by asking Denève of his impressions the morning after; so we began with the specific, moved to the general and ended rather than began with his early influences.

There was more sympathy than hilarity to begin with over the black eye I was sporting after having smashed into a post on my bike the day before. So RSNO communications manager Danny Pollitt took the snap pictured on the right, with the putative caption "conductor whops critic" (theartsdesk review of the concert, however, could hardly have been more favourable). Then I began by asking Denève of his impressions the morning after; so we began with the specific, moved to the general and ended rather than began with his early influences.

STÉPHANE DENÈVE: I've done the Symphonie fantastique quite often, I have to say, and the temptation is always to go further. With this piece I think there is a big danger to be more and more eccentric and overdo the effects, and I tried this week really so much - as I did a bit this summer when I did it with the London Symphony Orchestra - to keep, of course, my experience of nice colour effects and atmosphere and the psychedelic side, but to remember also it’s still a piece from the 1820s and that there is still a kind of classical aspect to it, a line to it. And that was really my goal to try and keep the crazy movie style of the piece but at the same time to preserve the sense of structure.

DAVID NICE: Absolutely, we tend to think of it as a programme piece, but what struck me especially in the first and third movements was how aware you made us of the symphonic structure. What especially struck me were the lower string lines, a lot of which I’ve never heard before, like that. Berlioz came across with astonishing clarity. My experience of your work is that you conduct these incredibly colourful pieces like Rimsky-Korsakov's Scheherazade with the London Philharmonic and Respighi's The Pines of Rome at the Proms, both very sensual with the most exquisite colouring. This time I heard more severity and it felt stricter.

Yes, indeed – and I’m delighted that you said that, because… it’s very strange the repertoire thing, because people just ask you for that and this and indeed somehow the miracle of the late 19th and early 20th century, it’s just fantastic repertoire. But when I was more an opera conductor, I used to do a lot of Mozart, and I lean to this classical aspect, to have a rapport with music which is a bit less sensual and a little bit more on the – discourse, the rhetoric, how you build the harmonies to make the tension of it, to just have this gradation.

It came across very clearly because the friend I went with, if I may say so, pointed out how genial and warm you were with the audience [notably in introducing the new work on the programme, Helen Grime's Virga], and that seemed quite a contrast with her impression of the Fantastique. She'd heard Dudamel and the Gothenburg Symphony Orchestra do it at the Edinburgh Festival and she said this was much more intellectual. I felt, not so much intellectual as a balance between the clarity of the line and the colour, which comes through more as the movements become more outlandish.

Absolutely, it becomes more a psychedelic dream…

No authoritarian gesture from any person can be as precise as what the music imposes

But I also found the second movement very scary, the bal [where the opium-drugged "hero" of the symphony sees his beloved through the whirling couples], the veiled quality of it, it was quite threatening.

Thank you, I’m so happy you said that, because this movement can also be just French charm and melody, and it has to start in a very opiumesque way, it feels to me like an old bar room which is dead and dark and then you remember things, like La traviata or La Valse, exactly. Then at the end it just gets really mad, maybe like in one of the novels of Berlioz where he gets crazy, his writing is just over the top, and he talks of this immense piano, revolutionary piano… He imagines that the piano is like a big mechanism and it gets bigger and it crushes people and there’s blood, and it’s like a total horror-movie vision.

I don’t know this story – it’s by Berlioz, you say?

It's called Euphonia, ou la ville musicale, this is one striking part of it, and I really love the idea in the bal movement, so many people just do ya ta ta-ta-ta-ta-ta ta-ta-dum [sings Berlioz's animez fast, bar 256] and have a new tempo straight away, and I really try my best - it’s difficult, because the orchestra just want to go for it - [sings the same rhythm more carefully] - to try and have something in the background which just accelerates and speeds more and more, but not connected totally with the phrasing, like a mechanical thing, and I want that to be quite scary and threatening somehow.

It's called Euphonia, ou la ville musicale, this is one striking part of it, and I really love the idea in the bal movement, so many people just do ya ta ta-ta-ta-ta-ta ta-ta-dum [sings Berlioz's animez fast, bar 256] and have a new tempo straight away, and I really try my best - it’s difficult, because the orchestra just want to go for it - [sings the same rhythm more carefully] - to try and have something in the background which just accelerates and speeds more and more, but not connected totally with the phrasing, like a mechanical thing, and I want that to be quite scary and threatening somehow.

You link the first two movements. I’ve heard the March to the Scaffold and the Witches' Sabbath joined together, but did you also want to hold the tension so that the second movement grows out of the first?

Absolutely, I have to admit, though, that there’s a little technical thing which I knew I didn’t achieve totally yesterday, which is too bad – I really want the second movement to start so soft that I try to hold the tension so that the audience doesn’t cough. Unfortunately, it’s my fault; I wanted a new Bärenreiter edition for this, so we played the new version, and there’s a page turn, so I was trying to hold the tension and say, OK, turn quickly this page, but then I could see they were not quite ready to go. And of course [imitates coughing] – the audience started up. By the way, I love this chorale at the end of the first movement. I was at the organ yesterday playing through the score, and I love this amazing idea of a piccolo playing a low G in the very last bars. So impressive after this manic-depressive symphonic movement which goes from one extreme to another in a bar, from crazy hysterical joy to deep gloom.

The players have to do their job, I’m not a beater as you can see, I don’t make them safe. With that level of musician, it's not necessary

It passed incredibly quickly, sometimes I’m just aware of it being rather big and long; it wasn’t fast, it was the feeling of tension. One thing especially struck me: I was a student at Edinburgh in the early 1980s so it was the end of the Gibson era… and then Neeme Järvi came along, which was so exciting, but even then the strings needed a lot of work. He was getting there, but last night I thought, this is a great string section at last; and at the Proms before that, too, the detail and articulation were so impressive. So you've done a lot of work there?

It’s an ongoing process, actually, and you know, yes, we do work specifically, and the most important things for the strings are articulation and length (rehearsing the RSNO, pictured below right). I really believe that all comes from the length of the notes, the sound can get buried so quickly. Look, the very start of the Symphonie fantastique, which I take extremely slow - there I have a kind of movie-theatre image of a fan turning, ta-da-da-da, in this solitary bar and this poor man just alone in this bar, kind of depressed, and the first memory [sings the muted first violin entry, very quietly], I imagine him just playing with his finger, something very intimate [carries on singing] so I ask the strings to play not only very soft the melody but also the rhythm too, like a voice that could stop at any moment. I’m very pleased, it took time, it was not there when I did it last time, but we could really afford then to have the right length of note and the right articulation even with those dynamics, which is very, very, very low.

And the Berlioz phrases – I know this is true of most symphonic music - they’re so vocal… Also what amazed me when the idée fixe finally arrives on violins and flute were the colours you got just in that virtually unaccompanied line, so much colour.

Oh, thank you, I feel humble, just respect the score, the amount of dynamics in this line just help it to sing – if you just respect them…

As in a Mahler score…

Exactly, it's so impressive, That’s why Mahler has the same feeling, he knows what he wants and he knows how to express it in the score, he’s actually incredibly precise. Actually, you’re right, I never thought about it, Berlioz is the only one along with Mahler who makes these little remarks [to the conductor] where he says, in the Fantastique [sings the flyaway staccato semiquavers], he says this is very difficult, the conductor should rehearse it properly. That’s another thing actually which if I may, sorry, I could speak about that for hours, but Berlioz puts a punta d'arco [at the point of the bow], and to be honest I would kill only for that rhythm, but when I see people getting it wrong… Berlioz knew what he wanted, he wanted takatakataka, of course it’s much less effective if it doesn’t have this spiccato, if it's just ahahahaha – because first the players say, what, a punta at this tempo? Yes, I say, at this tempo, let’s do it, and actually after a while, you have to work on it, it’s not instant, but it’s a real effect that Berlioz put; who knows better than Berlioz why he wrote that? We do it this way, it’s more risky, it’s more dangerous but I think it’s the right colour.

What I find fantastic is a piece that deals with the real musical element, this amazingly complex mixture of harmony, melody and rhythm, which creates a certain language

Berlioz runs the gamut of string effects, everything’s there, isn’t it?

Where does that come from? I’m always blown away. And the Treatise on Orchestration, I mean, how could he know so much the effect of this mixing?

Without having tried it out, you mean?

Almost, because when – and I know the music of his time was doing that, even if you can feel some operatic effects that may have been already at the time, but it’s just absolutely incredible, moving and strange.

And that’s something else that struck everybody last night – in a way, without wanting to copy it, if you were a composer working today, you would still think, I need to find sounds like that. Same with Sibelius, it seems to me. I did admire the Helen Grime piece, and I thought she had some good lines, but the sound right at the start is that sound I’ve heard from so many contemporary pieces. It’s not a fresh sound, and in a way the Berlioz felt more individual.

The fact is – the Helen Grime, OK I don’t normally like anything that sort of - sorry, I have to use clichéd words otherwise you don’t know what you think - avant-garde, Modernist piece with this kind of atonal noise everywhere. I just hate that, I don’t like it, I will never settle for that. That said, some of this music – it’s interesting, some people like Penderecki, who were very fine musicians but were obliged by the époque to do that, it’s curious because you feel that there is music behind the language which is inappropriate to them: with Penderecki, it’s funny, because here’s this avant-garde piece, the same music as he wrote before but without tonality.

In Helen's case, it could easily have been just like one more modern piece, like billions of them, but as soon as I heard it I thought there was something, a sort of power that surprised me, and I listened to it again, I was intrigued to listen to it, and I really think there is some fascinating melodic quality in the music, the building of the lines, which sits somewhere between the melodies of James MacMillan and Oliver Knussen. There's a little bit the feeling of MacMillan's earthy line, and Knussen's very analytic approach. It all seems very British to me. You're right, I don’t think she’s 100 per cent there yet, but for the sounds she did some very interesting mixtures that were not too clichéd.

It had a shape. I was a bit worried when in the talk before you conducted the piece she talked about "Impressionist" models, because those have such a backbone to them and so much contemporary music is all about process when it needs hooks...

Discourse, yes – the fact is, I totally agree with you that there must be a red thread in music and you should follow something that is happening, an elemental aspect, and very often you’re just lost. Some people are making a mistake, they think something is powerful because it’s a bit mysterious in the way that you can find some natural random thing mysterious. If you’re in front of a volcano, obviously you have those eruptions, it’s all random, you don’t know what’s next, and still it does give you a feeling of infinity, of power, and I think some modern music just uses this kind of feeling. If the composer has more than one or two gestures, which is sometimes the case, then of course you can become fascinated, but this is not a musical experience, it’s something different. It’s exactly the same as contemplating nature.

And I’m not interested in that – I prefer to contemplate nature, actually! What I find fantastic is a piece that deals with the real musical element, which is this amazingly complex mixture of harmony, melody and rhythm, which creates indeed a certain language, and I don’t think you can call something musical if there is not a language used. Which is why I do not believe in pure atonality without a key, because you need language, you need something to just follow.

Otherwise the music retreats in the listener’s mind into the background, you can start off thinking it’s arresting, and then you lose concentration as a listener – it’s obviously very different as a conductor because you have to deal with everything that’s going on in this complex score.

It's a bit like being in front of someone speaking another language that you don’t understand at all, you can notice some inflections, some funny things, but you lose concentration very quickly because you don’t know what it’s about. Out of the 10 pieces that I chose [for the contemporary strand in the RSNO's 2010-11 season] Helen's is probably most what you could call avant-garde.

[We discuss several of the other recent works programmed, including Peter Lieberson's Neruda Songs and Lindberg's Graffiti, one of his most tonal works, which Denève adores. And then to expand on MacMillan:]

I believe you've said that you admire The Sacrifice – you conducted the three orchestral interludes from it at the Proms.

I believe you've said that you admire The Sacrifice – you conducted the three orchestral interludes from it at the Proms.

I love that opera actually.

It’s amazing, I saw it in London and I hadn’t read the synopsis, so at the end of the second act, I literally couldn’t stand up, I was so shocked, and when did an opera last do that? Maybe Peter Grimes – it really does have that shock impact.

Wow – you didn’t know what was about to happen? Then it would be extremely shocking.

Musically he builds the tension, too, and I don’t find many new operas where the tension rises, they’re fragmented, and this just had a line through it. Would it be possible to do it in concert?

The full opera? Maybe, semi-staged, but I said to James I’d like to conduct it in a revival of the opera, I really find that absolutely fantastic. And the interludes to me are – I mean, the building of the second interlude, the Passacaglia, is absolutely incredible, and the choice of the right notes... I visited James at his home, actually, and I’m amazed, because he doesn’t really compose at the piano at all, and I was just amazed given all that harmonic complexity, it is exactly the right notes. I said, did you just have that in your mind?

That I’m really impressed by, because I’m always playing pieces at the piano, I’m rehearsing all the time, that’s what I do all the day, and I need the support to just get the harmonies in my body, to know where I am, and I can of course read the score in silence, but it’s very important for me just to check the material, and I’m very amazed, that he doesn’t really use a piano. He said sometimes he checks something when he wants to… and I discussed notes with him, actually, there were a few little mistakes in the score, and I could see texturally what he wanted – he’s a genius, I like him big time.

It’s exciting, isn't it: when I teach students, I tell them, if you come out of a piece scratching your head and saying, I don’t know what I think, it hasn’t worked – there has to be something in it that excites you even if you don’t understand it, and you find that with so few contemporary composers. It’s thrilling when it happens. Sometimes MacMillan is deliberately "effective", and rightly so if he’s writing the Violin Concerto or this wonderful Oboe Concerto that’s just been premiered, a fantastic piece.

Is it good? I don’t know this piece. When was it premiered?

About a month ago [at the time of the interview in 2010], first in Cambridge, then in London.

Wow, you were there? Bravo.

I’m a great fan of his. He was at Edinburgh more or less at the same time as I was, but I wasn’t in the music faculty so… I never met him there, but he is kind of a contemporary. So I think, my God, here’s someone of my age who really is a genius. Some of his pieces don’t work for me, but at the moment he seems to be on a creative spin.

Do you know, I discussed this with him, and I said, you’re more tonal, and for me that’s just better, and he said himself he was feeling more liberated, being freer with expression. He is maybe the last generation where you had this really heavy thing about Modernism, yes, he’s 50 just now, and that’s it – all the people under that age, apart from Germany and France somehow, but everywhere else in the world they’re more relaxed about what they can and cannot do.

I feel that conducting at the highest level is actually sharing with each other in the most sublime way

The postmodernist idea is really Stravinsky's, isn't it, that anything can be used, and it’s fascinating that the Stravinsky line got a bit squashed after the war by the Darmstadt experience.

Yes, they paid a high price for that, I think.

Do you have any working relationship with Pierre Boulez?

No. I have to admit, I’m not convinced – even by the conductor, to be honest, he’s one of those people about whom the French expression is they have a card, meaning that whatever they do it’s always great, and – I won’t tell some names - there are some artists and conductors you feel they have that card, and whatever they do it’s always great. I don’t like the idea that there’s this league, you are in the A-plus league, no, we all try to make music, right, and we have to be humble about that. But in his case, I don’t know why, people consider his conducting as always special, and I fail to find a recording that pleases me in every respect, I don’t know, he’s not my cup of tea, really.

It's admirable that he has such a fantastic ear, he can always tell if the second oboe is playing a wrong note. But perhaps that's not what conducting is really about. What IS the essence of conducting, for you?

To be together, not in a technical aspect, to be together in an almost – I’m not religious, but I would call it a religious sense, believe in the miracle of the order of… being accepting. I don't know, this is a philosophical question, but we are alone and so the only way to feel life is to share your humanity with somebody, and I feel that conducting at the highest level is actually doing that, is actually sharing in the most sublime way.

How do the authority and the democratic aspect combine? I mean, Abbado makes the musicians feel as if he’s giving them the gift to do what they want, his catch-word is "listen", but his immense authority is what gives the power to the orchestra.

You know, I’m a new parent, right [he and his wife Åsa have a young daughter, Alma] and I’m asking myself what it is to be a good father, and what means freedom, and I totally believe that freedom only exists within rules and retrocontrol, and when you conduct there’s no question that you are imposing many things, but for me the grail of conducting is when you are imposing the music in such a charismatic, logical way that it does actually come from the musicians musically; it’s a bit like when you’re in love with somebody and you walk hand in hand, it’s beautiful that at some point you don’t know who’s leading if you go left or right – it just happens because you look to the same direction with a common love, and I believe that.

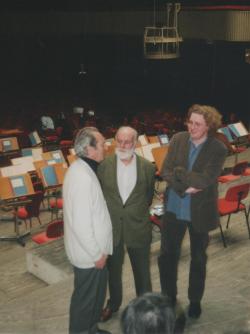

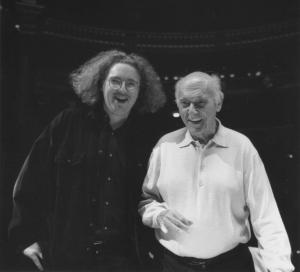

One of my biggest experiences of conducting – because I was five years pianist for the Orchestre de Paris and its chorus, so I played for many people there - was that I worked with [Carlo Maria] Giulini there (pictured right with chorus master Arthur Oldham and Denève in Turin). Playing for him three times just as if I were playing to you opposite, with the chorus - well, you could feel that this man had no doubts, but in such a way that you would give your best. So he was just believing in the miracle of what you would do and already accepting it, and there was no millimetre, no microsecond of doubt in his gestures...

One of my biggest experiences of conducting – because I was five years pianist for the Orchestre de Paris and its chorus, so I played for many people there - was that I worked with [Carlo Maria] Giulini there (pictured right with chorus master Arthur Oldham and Denève in Turin). Playing for him three times just as if I were playing to you opposite, with the chorus - well, you could feel that this man had no doubts, but in such a way that you would give your best. So he was just believing in the miracle of what you would do and already accepting it, and there was no millimetre, no microsecond of doubt in his gestures...

I remember in the Verdi Requiem where you have a tremolo and an amen, everybody playing or singing piano but with very different types of production of the sound. What you need to do there as a conductor is in one way very simple, the beat is just up, down, that’s all there is to it technically. Less so to just be able to accept people and be aware inside that they will actually just be with you, like I said all together as in the flow of the music, without any doubt. That happened with Giulini, it was miraculous, because it’s so simple, just being together in the most miraculously human way. That's what the power of music is in a way, when we really share something extraordinary, there is a love around, you can feel on rare occasions that people in the audience speak to each other and people forget boundaries between each other, we’re all there, and this is for me the dream.

Has it happened to you in any particular performance?

One moment I think was unique for me. I was conducting the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, a very fine orchestra, in a performance of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande [that evening when I asked him about his Desert Island Discs, Denève said unhesitatingly that his first choice would be the old Desormière recording, pictured left]. It happened in the famous interlude after the Absalom scene where Golaud, jealous of Pelléas, is violent towards his wife Mélisande and then you have this: [goes to the piano and plays from memory]...

One moment I think was unique for me. I was conducting the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, a very fine orchestra, in a performance of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande [that evening when I asked him about his Desert Island Discs, Denève said unhesitatingly that his first choice would be the old Desormière recording, pictured left]. It happened in the famous interlude after the Absalom scene where Golaud, jealous of Pelléas, is violent towards his wife Mélisande and then you have this: [goes to the piano and plays from memory]...

It's the pity for all that suffering...

...and suddenly you see where jealousy, which is the most terrible of emotions, can lead. There is such a sympathy at this moment for a man who just shocked you so much that you wanted to kill him. I was really in the mood, and at that moment, I lost it, just stopped to conduct somehow, and I really remember how I suddenly realised I had to wake up, because I was not conducting, I was vibrating... And I have actually listened to the recording: it’s more than together with an incredible sort of rubato feeling, and I do remember I was not conducting, I was – so I’m enthusing and of course I’m French so I will not speak about – oh, Alma and Åsa [the playing has summoned his daughter, followed by her mother]. But no, maybe it was telepathy, maybe I was just collecting the energy that was around, but these are special moments that you feel deeply.

Something strange happened last week, which was very interesting for me, I was with the Malaysian Philharmonic in Kuala Lumpur, and I started the second of two concerts featuring music from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet - I make my own selection - and suddently I broke my baton so I really had a baton this big [indicates with his little finger], so I just did the whole thing with this. And they reacted very nicely, so I tried to do something different, and it worked; it's just amazing, the communication with an orchestra. I really believe that what you see is only the emergent part of the iceberg, it’s what is behind that is important, just a knowledge of the music, actually. I think I understand the danger in the way in our époque conductors explain the music to the audience and show it as if they were listening to a CD - listen to this and that - it's a danger of the visual aspect of our world, I think conducting is not about that, conducting is really about all the music inside, and you should not conduct in showing things to the audience, it’s just about the inner logic of the music and pulse and tempo.

But you do quite like to talk to musicians, especially in rehearsals.

Oh yes, that's different – I speak quite a lot, sometimes too much, it’s my personal sin, you might say, because I have a lot of images in my head, and I love to get people to have the same feeling of it.

It’s like those singing teachers who communicate to their students entirely through images. Yours of the whirring fan at the beginning of the Symphonie fantastique, I imagine that would be very useful to me, to think of that.

Look, it was just an example, but for the start of the piece [sings his approach to the opening of the Symphonie fantastique again], what you want is not a start, you want the piece to be in motion already, so just if you give this idea that there is a fan turning before the music, people enter into it without doing a start, and so you don’t have to explain, look, I don’t want an accent on the first note, because often you hear TA ta ta ta ta ta... no, I want [sings softly, smoothly and evenly] da-da-da-da-da-da-da. I try to use a lot of things that come to my mind, and that’s maybe a bit random or scary, I have to say though that in America they love it because they love craziness, because the American culture is all about organisation and professionalism, so once I arrive they love it, so I’m lucky, I can be crazy in America, but in Europe I have to take care sometimes.

Musicians can be quite cynical about conductors talking a lot, and they’re not always aware of the overall effect, they tend to love conductors who give them an easy ride. What is your experience with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra players?

We've had our moments over the years - well, it’s a marriage, so you have to adjust somehow, but I hope I never impose too much. I listen to them when they have some advice, but I never compromise – I cannot do that anyway – I’m just made like that, I love details and I love to work. I use all my rehearsal time, I don’t usually let them go early. I mean when I conducted the Cleveland Orchestra for the very first time, I thought, oh, my God, such an orchestra, it’s fantastic for me, I’m a young conductor facing a tradition, I must just let them... but after two minutes I thought, oh no, no, no, even if you are the Cleveland Orchestra, because music is more important.

And they have to realise you’re all working for the greater good…

Oh yes, but look, I’m lucky, it works well here, and over the years the relationship with the RSNO is very good, and it’s a UK orchestra, they’re very polite, they will never be confrontational in any moments, so they know me and my way of working, I’m very pleased with the mood that we have over the years.

I’ve spoken to friends up here who don’t normally go to concerts, and they’re very much aware of you as a presence. I mean aside from the Broons thing [there had just been a presentation at Denève's house of the cartoon in question, its last frame with Scotland's first family acting as his "orchestra" reproduced below], the fact that you’ve made some kind of impact in the cultural world at large, to people that aren’t necessarily keen on going to concerts, but go to galleries, read books, that’s interesting, isn’t it?

Well, thank you, you say it, the audience has changed, huh? Look, the management has done a great job, we work hand in hand, and the whole organisation is spinning in the right space. I find that fascinating how you can just change the spinning style, everything just becomes logical and going in the right direction, and that’s how I feel. For me, if I may say, it’s a hugely successful experience, the RSNO, because we arrived somewhere with Simon Woods, and six years later we’re really somewhere else.

Because things had not been great – the Järvi years were fantastic and then there was, in my perception, a dip, and now with you it’s gone up again. I would say that the wind and the brass sections have always produced the most phenomenal sound and personality.

The woodwind section has always been good, when I arrived we had some issues because we needed oboe solo, we needed cor anglais solo, and we fulfilled that actually. I have to say also something that was very important since I arrived is that I have the title of Music Director, and it’s not for the title, I don’t care about that stuff, just that I wanted to say, look, I want to commit in every way, and I live here, and that’s what happened, I was involved in every appointment, I think you have to care a lot for an orchestra, it’s like kids…

You’re the father, or the patriarch. But as you said you have to make them feel you’re with them rather than above them, is that difficult for a conductor?

No, I don’t think so. Look, the whole world has changed so much in 20 or 30 years about the whole idea of social class, of respect – sometimes for the worse, I think we could have some more respect in this world sometimes, that’s another subject, but this idea – I know the model of the orchestra is a 19th-century model, of a dictatorship, but the order has changed now…

And when you think of Toscanini shouting …

I think we’re still dictators but we smile more [laughs].

You have to seem collegial but you need a will of iron.

Music cannot be done without this kind of relationship – you have to have a leadership somewhere, but the attitude of this fellowship is very naturally democratic, and there is a respect for each other, that goes without saying now, it’s just natural.

I think the first time I really sat up and listened was when you did that fabulous Prom in 2008, starting with the Second Bacchus and Ariadne Suite by Roussel, who's become something of a speciality for you, and ending with the best Debussy La Mer – no flattery, but I've heard it countless times in concert and I’ve never heard it more beautifully phrased, it’s such a difficult piece.

I have to admit this performance of La Mer at the Proms felt to me from my little history here quite an achievement – I try to be modest, but I’m not. That performance really showed the work we had done for – by then it was four years, because we spoke a lot, and I have a very strong view about Debussy, I love Debussy, and it was really something, that performance at the Proms, I remember really, really well how pleased I was. You need nine months for a baby, right, and you need some years for a good grape of wine, and that’s the same for music. Doing music overnight is possible, you can have an affair overnight, it’s possible, but it’s not the same as being married, it’s just another way. Though I love to be guest conductor as well, actually, I have to say, I don’t want to sacrifice that,

Because you can still have the spontaneity of the moment…

It’s different actually - the one-night stand - but building the orchestra’s confidence and knowledge, that’s different, and I really feel that, and I'm glad we shared that, because the music’s for us, not just for the audience, and it’s great when you can be together with this feeling (Denève pictured left with long-serving leader Edwin Paling and viola player John Harrington).

It’s different actually - the one-night stand - but building the orchestra’s confidence and knowledge, that’s different, and I really feel that, and I'm glad we shared that, because the music’s for us, not just for the audience, and it’s great when you can be together with this feeling (Denève pictured left with long-serving leader Edwin Paling and viola player John Harrington).

And you want to record Debussy…

Everything orchestral, yes, for Chandos, we're doing a two-CD set next season, that will be my Debussy year [2012 will be the 150th anniversary of Debussy's birth], and my dream is to make that a summary of my time here. We did La Mer at the Proms and on tour, we also did Iberia in the Spanish tour, so we did a fair amount.

But you haven’t typecast the orchestra in French repertoire in the way that Järvi tended to do, magnificently, with Prokofiev and Shostakovich, you’ve kept it quite wide…

Thank you for noticing it, because the media are not often as deep and thoughtful as you are, they say, oh he’s a French conductor. Actually I can prove, given time, that our programming has been very eclectic, we touch everything, I didn’t make the French repertoire THE thing. The only composers I sacrificed a little, and I suffer about that, have been Bach, Mozart, Haydn...

But in opera, you've conducted a lot of Mozart...

I actually covered 25 different operas in Dusseldorf during the four years I was Kapellmeister at the opera there. It's not in my biography. It’s a huge organisation, and I profited from the time there, it was a good all-round experience in a German house.

And had you repetiteured, accompanying singers at the piano, before that?

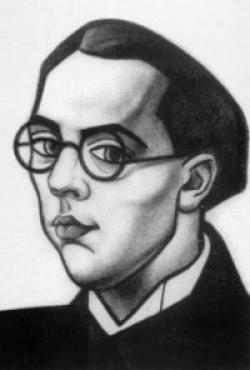

Actually I carried on with that in Dusseldorf by choice. I had 30 performances a year, and I preferred to prepare them with the soloists in the good old repetiteur way. You know, it’s an ensemble, it’s a repertoire opera, so the soloists are always there and you can rehearse Don Giovanni in October if the performances happen to be in March. So I did rehearse at the piano a lot. Actually I miss a little bit that work, you cannot do everything, right, I’m a father now. But as far as the repertoire went I did touch a lot of different styles - earlier, especially. For Bach, for instance, I’m from the north of France, Flanders (pictured right, a very young Denève), I’ve been educated in Herreweghe, Malgoire, Kuijken, and I cannot really listen to Bach played on modern instruments. That limits, of course, the repertoire.

Actually I carried on with that in Dusseldorf by choice. I had 30 performances a year, and I preferred to prepare them with the soloists in the good old repetiteur way. You know, it’s an ensemble, it’s a repertoire opera, so the soloists are always there and you can rehearse Don Giovanni in October if the performances happen to be in March. So I did rehearse at the piano a lot. Actually I miss a little bit that work, you cannot do everything, right, I’m a father now. But as far as the repertoire went I did touch a lot of different styles - earlier, especially. For Bach, for instance, I’m from the north of France, Flanders (pictured right, a very young Denève), I’ve been educated in Herreweghe, Malgoire, Kuijken, and I cannot really listen to Bach played on modern instruments. That limits, of course, the repertoire.

But you could in effect conduct the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment?

I could, I would love to, but I don’t have this image at all, people don’t know about that background. It’s OK. But I wish I could conduct a Bach St John Passion. It was my biggest shock when I was 16 to go to listen to the St John Passion with Franz Brüggen, in Amsterdam – aaach, I still have the sound in my head with that special Baroque oboe playing, and I’d love to do that. But in the economy right now, apart from the OAE, all the ensembles like that they are owned by their conductors, by Christie, Minkowski, Rousset, Haim, and so you cannot really be guest conductor. Maybe I’m wrong but I wouldn’t do a St John Passion with modern instruments.

Going to performances every night in Paris was for me the way I learnt... certainly I was a freak

I suppose there are conductors like Mackerras who did both, who applied authentic lessons to the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, for example, which is possible. What other revelations were there? You mentioned the Brüggen St John, what else has hit you like a coup de foudre?

Ah, that’s good. Recently one of the most impressive concerts I’ve heard, we speak about, was Tchaikovsky Five with Gergiev and the Mariinsky, which I thought was… all you dream about this music was there, I really adored that, and I’m kind of fascinated by Gergiev, sometimes it’s very uneven but when it’s great, it’s great.

Also in his rehearsals he’s really precise. I loved how in a documentary the LSO tuba player Patrick Harrild said Gergiev could make a phrase out of two notes.

That's beautiful, I like that. No, it’s very special. Coming back in time, I do remember extremely strongly, in fact I spoke a couple of days ago to Frank Peter Zimmermann [violinist in his concerts] he was the soloist in a Mozart violin concerto in the concert I'm talking about, back in 1991. I was a young student at the Paris Conservatoire and this was with the Orchestre National de France conducted by Georges Prêtre (pictured left with Denève by Eric Mahoudeau). I thought it was revelatory, the way Prêtre was phrasing with the orchestra, the way he was interacting, I had this feeling that the same blood was in him, it was a cultural thing, it was my culture.

That's beautiful, I like that. No, it’s very special. Coming back in time, I do remember extremely strongly, in fact I spoke a couple of days ago to Frank Peter Zimmermann [violinist in his concerts] he was the soloist in a Mozart violin concerto in the concert I'm talking about, back in 1991. I was a young student at the Paris Conservatoire and this was with the Orchestre National de France conducted by Georges Prêtre (pictured left with Denève by Eric Mahoudeau). I thought it was revelatory, the way Prêtre was phrasing with the orchestra, the way he was interacting, I had this feeling that the same blood was in him, it was a cultural thing, it was my culture.

What was the work?

Funnily enough it was not the French repertoire, not La Valse, it was Mahler One, can you believe. And retrospectively, I don’t think that Mahler One was very idiomatic, not really a typical Mahlerian sound, but the French way the conductor had, was really a big shock to me, and I remember thinking that’s what I imagine doing. Then I was not doing that anyway.

Who taught you conducting?

Actually when I was growing up in the north of France, I joined a little conducting class when I was 14, so I started very early. Then I formed my own little ensemble when I was 16, 17, then I went to the Paris Conservatoire at 18 and I was student of a guy who, I have to admit now with all my respect, I don’t think taught me a lot. The way I learned was just to conduct at the Conservatoire, just to do it, and what I have to say, I learned a lot looking at conductors, I had crazy ideas during my years at the conservatoire (pictured right more recently in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with Scotland's First Minister Alex Salmond on an RSNO tour of France). Every single night I was at a show, because we had six free tickets for the Opera every night, and ten at the Orchestre de Paris, and I was always there – because, believe it or not, those tickets were not always used.

Actually when I was growing up in the north of France, I joined a little conducting class when I was 14, so I started very early. Then I formed my own little ensemble when I was 16, 17, then I went to the Paris Conservatoire at 18 and I was student of a guy who, I have to admit now with all my respect, I don’t think taught me a lot. The way I learned was just to conduct at the Conservatoire, just to do it, and what I have to say, I learned a lot looking at conductors, I had crazy ideas during my years at the conservatoire (pictured right more recently in the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées with Scotland's First Minister Alex Salmond on an RSNO tour of France). Every single night I was at a show, because we had six free tickets for the Opera every night, and ten at the Orchestre de Paris, and I was always there – because, believe it or not, those tickets were not always used.

There should have been a queue; sometimes it was, sometimes for Pavarotti, say, we had to queue for a few hours to get them, there was a bit of a mafia, but often it was just available. So I saw a series of performances, I saw all 16 Nozze di Figaros in the run. That was for me the way I learnt. I have to say, certainly I was a freak. You have to understand, I’m from a simple working-class family, and I’m from the provinces, a small town, Tourcoing, near Lille; when I arrived in Paris, all life was there, the teachers were people I knew from CDs, I was what we call a midinette...

...like Balzac’s provincials coming to the great city for the first time...

And everything amazed me, I was a very enthusiastic type, and I would love to discuss for ever about performances and singers, and I really heard everybody. I could show you, I still have piles of tickets for everything I saw. Solti was also actually a kind of shock for me, I became his assistant by the way (pictured left with Solti). Just on production. I worked on the Don Giovanni recording...

And everything amazed me, I was a very enthusiastic type, and I would love to discuss for ever about performances and singers, and I really heard everybody. I could show you, I still have piles of tickets for everything I saw. Solti was also actually a kind of shock for me, I became his assistant by the way (pictured left with Solti). Just on production. I worked on the Don Giovanni recording...

...his second one, with Bryn Terfel...

Yes, you forget, I'm much too young to have worked on the first! Actually I can show you something funny [and he pulls up on his laptop an archive film of himself as a young pianist seen in his apartment and then working with Solti and the great singers of that cast]. I was 24...

[We see him taking over orchestra and soloists in the Act II Sextet] Why is he getting you to conduct?

He wanted that, he liked to listen from out in the hall. It’s actually – that’s a funny archive – he explained to me why actually, he showed me a wonderful photo of himself with Richard Strauss -

Ah yes, he told me that story, when Strauss said, "Go out into the hall and listen..."

And how Strauss came out in front of the orchestra and said to Solti, "that was good, too bad I can’t hear the singers". Solti felt a bit humiliated in front of the Staatsoper Orchestra. And from there he decided always to check balance…

What an incredible connection - that Solti conducted the Rosenkavalier Trio at Strauss's funeral, where the women broke down and then came back in one by one before the end. You feel privileged to have such links with an incredible past...

Yes, I feel very lucky, it’s thanks to Paris that I could see so many people and such great concerts. I played for Wolfgang Sawallisch…

He’s a very good pianist too.

Well, Solti was a good pianist too, that’s how I met him. I played for him the Beethoven Missa Solemnis, which is incredibly difficult on the piano, especially at his tempo [sings], and he was happy with me, I was lucky, and then I played for his rehearsals of Bartok's Bluebeard’s Castle and – that was incredible, he said to me, "OK, mein liebe, tomorrow you will conduct." I thought I would only be playing the rehearsals, but actually he gave me the score, and I had a short night, and I took the score home with me, I remember thinking, that’s Solti’s score, and the next day I conducted a part of the rehearsal with the Orchestre de Paris, and he was very happy.

So he was your maître, as it were?

Our time together was short, because he died shortly afterwards. Actually I have only one maître who is this man [takes down a photograph from the mantelpiece], you won’t know him – André Dumortier (pictured right). He was a great pianist, he was one of the finalists of the Concours Eugène Ysaye [subsequently the Queen Elizabeth Competition], the very first one with Michelangeli and Gilels in 1938. Then he made quite a big career, he had a problem with a finger, then he made another big career as a teacher. I saw him from when I was 15 to when I was 19, twice a week for the entire morning. I’m a real disciple, but I don’t believe so much this culture of masterclasses, like pressing every orange to have the juice of everything. I believe you have to follow your own culture, and too bad if you choose the wrong person, you have to be smart, and I really followed his culture – he’s Belgian, by the way.

Our time together was short, because he died shortly afterwards. Actually I have only one maître who is this man [takes down a photograph from the mantelpiece], you won’t know him – André Dumortier (pictured right). He was a great pianist, he was one of the finalists of the Concours Eugène Ysaye [subsequently the Queen Elizabeth Competition], the very first one with Michelangeli and Gilels in 1938. Then he made quite a big career, he had a problem with a finger, then he made another big career as a teacher. I saw him from when I was 15 to when I was 19, twice a week for the entire morning. I’m a real disciple, but I don’t believe so much this culture of masterclasses, like pressing every orange to have the juice of everything. I believe you have to follow your own culture, and too bad if you choose the wrong person, you have to be smart, and I really followed his culture – he’s Belgian, by the way.

And how would you sum up that culture?

As my piano teacher, he became more philosophical and everything, though it was about the music, of course, but he was somewhere between the Lisztian and the Russian pianist culture of Neuhaus and so on, he was a student of Arthur de Greef. So somehow, which I love by the way, he’s a great mix between the north of Europe which is a bit more protestant, a bit more serious, a bit more austere, organised and sentimental, and slow and profound somehow, and the Latin influence of the South, which is more fantastical, more colourful, more bloody, more external. I like Belgium for this mix. That's what I love in the music of Roussel, too, who was born around the same time as De Greef, the mix of the two influences, you can really feel both the mathematic organisation, the very serious part of Roussel, and the sense of flamboyance. What I worked at most with Dumortier was a sense of the composer's time. He was so concerned about what is inside the style, and he was so much trying to educate me about everything, philosophy, literature, painting, and he was always extrapolating… if we were doing the Schumann we would do everything that could link, to breathe the same air. I totally believe in art that style is the key.

…that you don’t impose your own?

I think so. Because if you are an artist your personality will be there, so you don’t need to push that part, the subjectivity will be there, otherwise you’re nobody, so the thing I think is just to try to be true and I love that. That’s my Belgian part, my scholastic part…

Would you call yourself Belgian in any way?

I’m not, I wish I could, I’m from the borderline, but I’m still French... [Frank Peter and a mutal friend from Sweden arrive for lunch.]

I don’t have this competitive thing, like I have to conduct this or that… I just want to make music with musicians I love

Is there anything else, or any composer, that is a grail, a style you're waiting to investigate?

Actually I tell you what is my recent dream, to become if I’m lucky, the Koussevitzky or the Paul Sacher of our time, I would like to be the person that has the right taste to commission the right piece from the right person. I try to know as much as I can about what is there and around, I would love to really be more involved in new music but it’s a question of taste, you have to believe in your taste, and I think our world has been following too much some snobbish idea, I think you have to be a free mind and say, I like that, I want to promote that, no matter what other people think about it…

...avoiding the fashionable trend.

Exactly, I think we are really a world of followers, there’s no ideology in our époque, my generation has no ideology, and this is somehow good, because we have to heal after communism and fascism, ideologies that failed miserably in the 20th century. But the bad side is that everything is very shallow, we are followers, and I would love to be a free mind and I will work on it. I want to have the most individual taste… that’s my goal, I never had really dreams like, oh, I want to conduct the Berlin Phil as my ultimate dream. No, I’m from a simple family and everything that’s happened has been a bonus – going to Paris was a bonus, the feeling that I escaped my scheme to be a professional builder like my father, all of that has just been a bonus. So I don’t have this competitive thing, like I have to conduct this or that… I just want to make music with musicians I love, and I always have the same pleasure going with not so great an orchestra from there to there [wide gesture] as going with the Philharmonia from there to there [narrower gesture]. That’s a way that’s interesting, not the goal. I’m trying to search if there’s some dream piece. I’d like to do again Pelléas et Mélisande, because I did it only once, but I’m not a megalomaniac, I don’t dream to conduct Mahler Eight.

If it happens, fine...

There’s so much repertoire, and I could concentrate on so many things different, sometimes I long for Bach but I'm pushed a bit by the wind; you cannot decide everything, you have to compromise, people want this or that repertoire, this soloist wants to do this piece. So what I love is that now I will have a new experience, having had such a feeling of success with the RSNO, I hope that my next experience will not be a straight repeat – I’m going to Germany to a radio orchestra [in Stuttgart, where he has already taken up his post for the 2011-12 season]. It will be a different kind of culture and hopefully another story.

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Comments

What an amazing and